The paper “Role of test motivation in intelligence testing” (2011) by Duckworth et al. is widely cited as evidence that IQ is not important, invalidating the “IQ thesis”. They found that motivation strongly impacts IQ scores and the predictive validity of IQ for life outcomes is diminished after accounting for test motivation. There is a huge misunderstanding. As Duckworth et al. pointed out :

It is important not to overstate our conclusions. For all measured outcomes in Study 2, the predictive validity of intelligence remained statistically significant when controlling for the nonintellective traits underlying test motivation. Moreover, the predictive validity of intelligence was significantly stronger than was the predictive validity of test motivation for academic achievement. In addition, both Studies 1 and 2 indicate that test motivation is higher and less variable among participants who are above-average in measured IQ. These findings imply that earning a high IQ score requires high intelligence in addition to high motivation. Lower IQ scores, however, might result from either lower intelligence or lack of motivation. Thus, given closer-to-maximal performance, test motivation poses a less serious threat to the internal validity of studies using higher-IQ samples, such as college undergraduates, a popular convenience sample for social science research (43). Test motivation as a third-variable confound is also less likely when experimenters provide substantial performance-contingent incentives or when test results directly affect test takers (e.g., intelligence tests used for employment or admissions decisions).

But what is the relation with “g” (i.e. the general intelligence factor) ? Here, the motivation gap doesn’t translate to g gap. Test incentives could only work for the purpose of the experiment, with no impact on real life outcomes. That the score gains were more pronounced for lower IQ participants tells us nothing about the malleability of IQ by means of educational programs, which all failed to produce lasting effects on IQ. And given that the two groups of subjects have been subjected to different conditions, external bias may have occurred (Jensen, 1980, ch. 12). Thus, conceptually, if IQ scores can be achieved through different pathways, as the authors imply (e.g., either intelligence or motivation), then measurement bias should be detectable. But empirically, this is not what is usually seen. Now we come to the technical problem with the study. The blogger Statsquatch deals a fatal blow to Duckworth’s IQ-motivation study :

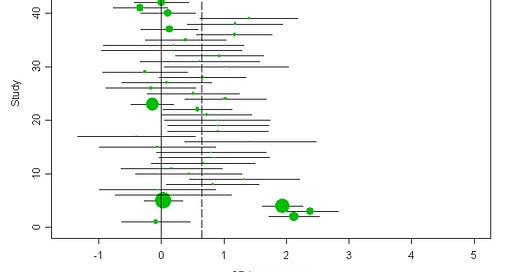

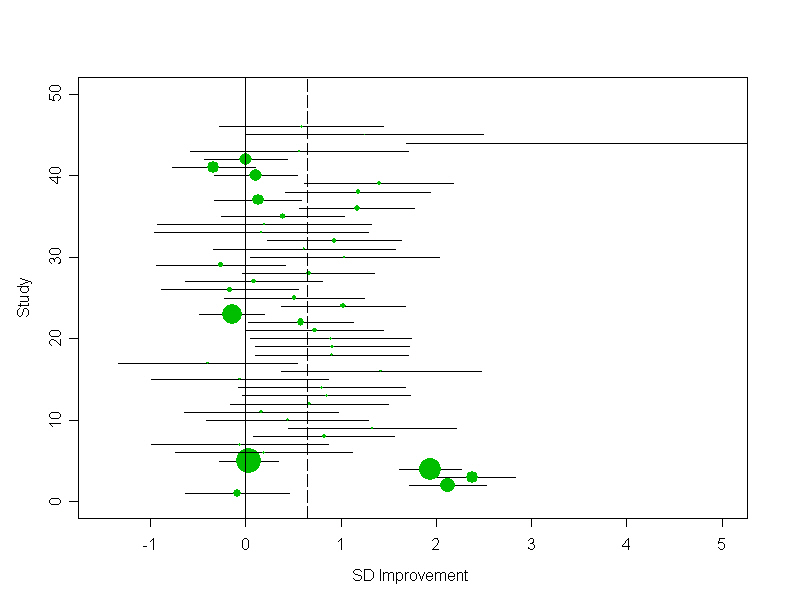

The paper’s meta-analysis of the 46 studies was very good but they neglected to make a “forest plot” that graphs the effect sizes and confidence intervals from each study. So I did it. The size of the effect circle is proportional to the inverse of the effect’s standard error, i.e., bigger studies that get more weight have bigger circles.

Two things are apparent: the study outcomes are highly variable, i.e., they are heterogeneous, and there are only three large experiment (2, 3, and 4 in the graph) that showed motivation leading to a large improvement in IQ score and hence are very influential.

The three experiments were run on special ed kids and written up in one paper by Bruening and Zella (1978) while the first author was at the Oakdale Center for Developmental Disabilities. A few years later Bruening admitted to fabricating data for other experiments on retarded kids at the same center and the case became a text book example of scientific fraud. Although there were no allegations of fraud on the 1978 paper, I re-ran the meta-analysis with out Bruening’s data and found the the estimate (using the random effects model) was now 0.48 SD and was no longer significant ( p = .07). This makes me uneasy about accepting Duckworth’s results without further replication.

Interestingly, this is not the first time the first author was under fire. Here’s what Sackett et al. “High-Stakes Testing in Higher Education and Employment” (2008) had to say about Duckworth’s previous study “Self-Discipline Outdoes IQ in Predicting Academic Performance of Adolescents” (2005) on motivation/self-discipline :

“They applied a range restriction correction to one of the six outcome measures (GPA) and reported that whereas the corrected IQ–GPA correlation (.49) was larger than the uncorrected value (.32), it remained lower than the self-discipline–GPA correlation (.67). Although this is true, note that their conclusion (self-discipline accounts for more than twice as much variance as IQ) no longer holds after one takes range restriction into account. In addition, we applied range restriction corrections to other outcomes; in the case of predicting procrastination (as measured by the time homework was begun), for example, IQ had a higher correlation (-.28 corrected, -.18 observed) with procrastination than did self-discipline (-.26) after we corrected for range restriction, which is clearly at odds with the authors’ conclusion.”

There is, however, something that nobody seems to notice. One glaring problem with Duckworth’s theory is the implication that motivation is a largely malleable trait (i.e. modifiable by means of parental education). The role of motivation/self-discipline in school achievement is meaningful only given the assumptions that motivation/self-discipline is 1) largely malleable and 2) largely independent of IQ. For the first proposition, most behavioral traits are under genetic influences (Rowe, 1994). For the second proposition, Jensen (1980, p. 322) mentioned that it is success (failure) itself that enhances (dampens) motivation.

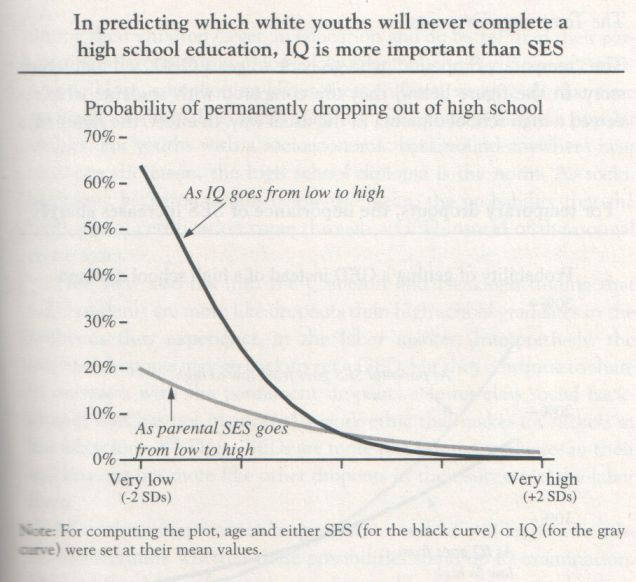

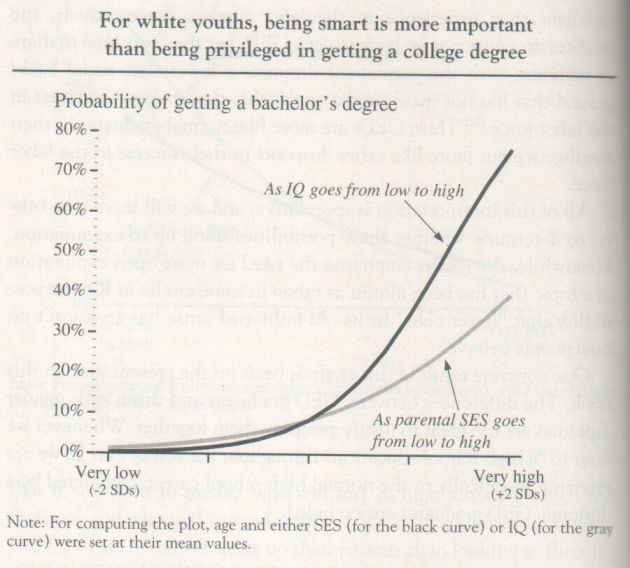

Let’s assume motivation is highly malleable and more important than IQ in predicting school achievement, in this case we must expect that parental SES (socio-economic status) is more important than IQ in predicting, e.g., educational attainment because high SES parents may foster motivation of their children for cognitive-related tasks due to providing better cognitive environments. So they should have higher levels of test motivation due to willingness of doing well. However, when we compare the independent role of IQ and the independent role of SES on school achievement, we can notice that IQ (when parental SES is held constant) is much more important than parental SES (when IQ is held constant) in predicting the probability of getting a college degree and the probability of permanently dropping out of high school. From the Bell Curve (1994, pp. 148, 153):

Of the whites who dropped out never to return, only three-tenths of 1 percent met a realistic definition of the gifted-but-disadvantaged dropout (top quartile of IQ, bottom quartile of socioeconomic background.)

In terms of this figure, a student with very well-placed parents, in the top 2 percent of the socioeconomic scale, had only a 40 percent chance of getting a college degree if he had only average intelligence. A student with parents of only average SES – lower middle class, probably without college degrees themselves – who is himself in the top 2 percent of IQ had more than a 75 percent chance of getting a degree.

The effect of parental SES is not sufficient enough to support the motivation theory. We must recall that IQ is an important predictor of longevity, car accident, work accident (Gottfredson & Deary, 2004). IQ also predicts - beside other factors - lower crime rate, illegitimate birth rate, divorce rate, and so on (Gottfredson, 1997, 2002). Motivation can’t account for all of these social outcomes.