After the global financial crisis in 2008-2009, the global debt increased substantially and was mainly driven by governmental and nonfinancial corporate debt. However, the rise in nonfinancial debt occurred mainly within emerging economies (Abraham et al., 2020). In China, nonfinancial corporate debt increased from 98% in 2008 of GDP to 152% in 2018. As of now, China still did not recover its high growth prior to 2008. This article will examine the most plausible causes: fiscal stimulus, debt ratio, SOEs. How much these factors explain the slowing growth is a question left for later.

The Inefficiency of State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs)

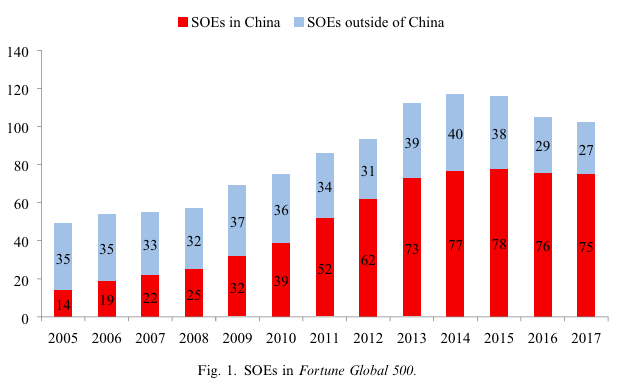

SOEs constitute a huge part of China’s economy, due to its influence on both the domestic and global markets. It is therefore remarkable that China became such a powerful country despite the sub-optimal performance of SOEs.

To understand the Chinese debt, we must first understand its corporate economy. Lin et al. (2020) provide an excellent overview. In China, firms can be roughly divided into private and state-owned enterprises, respectively, non-SOEs and SOEs. The SOEs plan their production according to predetermined plans issued by the government, without considering setting product price and the demand of customers. All profits made were remitted to the state and losses were covered by the state. Despite multiple rounds of reforms over the decades, SOEs are largely inefficient compared to non-SOEs.

The first reforms started in the late 1970s as a solution to overcome the economic distress caused by the Cultural Revolution by giving SOEs rights of independent production and operations but the reform expanded only to a limited degree. From 1984 onwards, the SOEs’ managers were given operating rights through employment contracts which created short-termism because most government-manager contracts lasted 3-5 years. China deepened the reform in the 1990s by introducing and further developing the capital market. However, the system was still inefficient as many SOEs reported negative earnings and redundant workers had to be laid off. SOEs still suffered from the agency problem and ambiguous property rights. In 2003, China established the SASAC, a public agency, to fulfill the role of shareholder for large SOEs on behalf of the central government. For the last reform, in 2012, the SASAC facilitated the merger of 20 central SOEs for promoting competitiveness of SOEs and reducing surplus capacity.

The problem deepens when considering the financing source of SOEs. Lin et al. (2020) tell us that the Chinese government owned 67% of the four largest Chinese commercial banks in 2017. State-owned banks prefer to lend to SOEs and discriminate against private firms. Generally, banks lend to SOEs because they can build connections with local government officials and obtain benefits from these political ties and because SOEs are deemed less risky due to the public bailout.

Lin et al. (2020) finally review an extensive body of research showing that SOEs which were privatized performed better than SOEs which did not incur private ownership change (Park et al., 2006), that SOEs incur significant agency costs when state shareholders (i.e., the government) tend to maximize political benefits instead of maximizing corporate profits (e.g., Fan et al., 2007), that this type of government intervention is the main obstacle to operational efficiency and investment in China’s listed SOEs (Jiang et al., 2010).

Iwasaki (2022) meta-analyzed the relationship between state ownership and firm performance across emerging countries, e.g., EU eastern states, Russia or China. The negative (but small) relationship is consistent across these countries. On the other hand, the three other types of ownership (e.g., domestic outside, foreign, managerial) showed a small positive relationship in either EU eastern states or China but a strong positive relationship in Russia.

Obviously, SOEs being inefficient does not explain the slowing growth after the subprime crisis, but it helps understand the argument of the following section.

The Fiscal Stimulus That Hurts Long Term Growth

Huang et al. (2020, Tables 9-10) investigated the long-term impact of the Chinese fiscal stimulus in 2009 in response to the Great Recession by way of regression analysis to predict firms’ investment using lagged values of investment, revenue growth, cash flow and the interaction of cash flow with local government debt (but not including its main effect) along with firm-level and city-year fixed effects. For private firms, the positive regression coefficient of cash flow and its interaction with local public debt indicate that higher local government debt crowded out private firms’ investment by making them more dependent on cash flow (i.e., internal funds). For state-owned firms, the lower regression coefficient of cash flow and its non-significant interaction with local public debt indicate that public debt does not affect the financing constraints (proxied by cash flow) of public firms. They also found (Figure 3) that the increase in local government debt to GDP is associated with declines in investment ratios of private industries more dependent on external financing dependence (EFD), which is a measure of a firm’s use of debt or equity issues to finance operations/investments.

Cong et al. (2019, Table 5) carefully examined the impact of the fiscal stimulus during the stimulus years (2009-2010) on firm-level outcome. They found that SOEs received more bank credit than non-SOEs. The average product of capital (log APK) displaying a positive coefficient for non-SOEs but a value of zero for SOEs indicates that SOEs benefited from the increase in credit supply independent of their productivity whereas non-SOEs benefited more if their productivity was higher. Furthermore, the negative coefficient of credit-supply*APK interaction for non-SOEs (but positive and non-significant coefficient for SOEs) indicates that less productive firms among non-SOEs receive relatively more bank credit. Overall, this behaviour might be driven by implicit government guarantees. Importantly, they emphasized that this is a reversal of the process of capital reallocation toward productive private firms that characterized China’s high growth up to 2008.

Crowding Out by State-Owned-Enterprises

Zhang et al. (2022) analyzed data from 2008 to 2019 and found that central government debts (through Treasury bonds) and local government debts (through their financing vehicles) with 1 period lag had negative regression coefficients on corporate bonds and corporate loans, respectively. Taken together, this means government debts (or bonds) crowd out private investment. However, the negative effect weakens when local government fiscal health improves or when the size of the lending market increases.

Xia et al. (2021) found, based on data from 2000-2018, that lagged values of local government debt crowded out non-SOEs leverage (measured in debt to asset ratio) but not SOEs leverage, even after controlling for provincial differences in GDP.

Liu et al. (2023) showed that local government debt exerts a strong crowding out effect on local enterprises, especially among non SOEs. However, the crowding out effect comes from government financing through bank loans, not through government bonds.

Zhang & Huang (2022) found that the increase in bank competition leads to decreases in the probability of forming zombie firms in non-SOEs but increases the probability among SOEs. This is because intensified competition provides them with credit below the market interest rate. Bank competition also decreases the degree of information asymmetry (measured with management expenditure) between banks and firms. Deregulation of foreign banks decreases loans for underperforming firms. Not surprisingly, marketization is accompanied by less non-market-oriented credit behavior (e.g., banks are less willing to bail out underperforming companies after bank deregulation).

Consistent with this finding, Gao et al. (2021) found that deregulation increases size, net income growth and profitability of non-SOEs but not SOEs. But because deregulation is typically accompanied by new entrant banks, who usually don’t have access to ample information on local firms yet, the existence of SOEs with their government guarantees and soft budget constraints crowds out productive investment since new banks lend more to SOEs. These authors (Table A9) also showed evidence that SOEs are less efficient than private firms. Although these authors wrongly concluded that “deregulation leads to a worsening of credit allocation across firms, i.e., more bank credit flowing into SOEs, especially for inefficient ones with higher political rankings and softer budget constraints.” The existence of the SOEs, not the market, was the real anomaly.

Wang et al. (2022) reported that SOEs enjoyed inflated ratings from the credit rating agencies (CRAs). Perhaps more concerning is that their overratings are less informative (i.e., less predictive) of their credit default risk than their matched non-SOEs, which implies that credit ratings for SOEs are driven more by their government backing than by their actual financial fundamentals. This creates inefficient allocation of capital because these companies are perceived as less risky than they really are and eventually receive bailout funds.

High Debt Ratio Dilemma

At the heart of the problem is the local government debt which increased from 7.5% to 24% of GDP over the 2006 to 2019 period in China (Zhang et al., 2022). As everyone now should know, since the influential work by Reinhart & Rogoff (2010) who studied the nonlinear effect of debt on growth, countries with high debt-to-GDP ratio display lower economic growth.

Using an autoregressive distributed lag model on 2015-2022 data, Cheng et al. (2022, Tables 2-3) found a threshold of 40% or 20% debt/GDP ratio for local government debt using a lag value of 1 or 2, respectively. Above this threshold, the debt ratio lowers economic growth. Regardless of the threshold however, increases in local government debt lead to lower economic growth in the long term, and the relationship is robust even after adding inflation as a control variable. Although displaying a lower effect, inflation is negatively correlated with growth. The authors argue this lower effect is mainly due to inflation targeting policy.

References

Abraham, F., Cortina Lorente, J. J., & Schmukler, S. L. (2020). Growth of global corporate debt: Main facts and policy challenges. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, (9394).

Cheng, T., Qiu, L., & Chen, J. (2022). Local Government Debt and Economic Growth: Evidence from China. Available at SSRN 4341358.

Cong, L. W., Gao, H., Ponticelli, J., & Yang, X. (2019). Credit allocation under economic stimulus: Evidence from China. The Review of Financial Studies, 32(9), 3412–3460.

Fan, J. P., Wong, T. J., & Zhang, T. (2007). Politically connected CEOs, corporate governance, and Post-IPO performance of China’s newly partially privatized firms. Journal of financial economics, 84(2), 330–357.

Gao, H., Ru, H., Townsend, R., & Yang, X. (2021). Rise of bank competition: Evidence from banking deregulation in China. Hong Kong Institute for Monetary and Financial Research (HKIMR) Research Paper WP No. 27/2021.

Huang, Y., Pagano, M., & Panizza, U. (2020). Local crowding‐out in China. The Journal of Finance, 75(6), 2855–2898.

Iwasaki, I., Ma, X., & Mizobata, S. (2022). Ownership structure and firm performance in emerging markets: A comparative meta-analysis of East European EU member states, Russia and China. Economic Systems, 46(2), 100945.

Jiang, G., Lee, C. M., & Yue, H. (2010). Tunneling through intercorporate loans: The China experience. Journal of financial economics, 98(1), 1–20.

Lin, K. J., Lu, X., Zhang, J., & Zheng, Y. (2020). State-owned enterprises in China: A review of 40 years of research and practice. China Journal of Accounting Research, 13(1), 31–55.

Liu, Q., Bai, Y., & Song, H. (2023). The crowding out effect of government debt on corporate financing: Firm-level evidence from China. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 65, 264–272.

Park, S. H., Li, S., & Tse, D. K. (2006). Market liberalization and firm performance during China’s economic transition. Journal of International Business Studies, 37, 127–147.

Reinhart, C. M., & Rogoff, K. S. (2010). Growth in a Time of Debt. American economic review, 100(2), 573–578.

Wang, Y., Fang, H., & Luo, R. (2022). Does state ownership affect rating quality? Evidence from China’s corporate bond market. Economic Modelling, 111, 105841.

Xia, X., Liao, J., & Shen, Z. (2021). The Crowd-Out Effect of Government Debt on Firm Leverage. In E3S Web of Conferences (Vol. 235, p. 01023). EDP Sciences.

Zhang, M., Brookins, O. T., & Huang, X. (2022). The crowding out effect of central versus local government debt: Evidence from China. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 72, 101707.

Zhang, X., & Huang, B. (2022). Does bank competition inhibit the formation of zombie firms?. International Review of Economics & Finance, 80, 1045–1060.