Capitalism: A Treatise on Economics

by George Reisman, 1996.

CHAPTER 15 AGGREGATE PRODUCTION, AGGREGATE SPENDING, AND THE ROLE OF SAVING IN SPENDING

Application to the Critique of the Keynesian Multiplier Doctrine

As should now be clear, any rise in wages, in the demand for goods at wholesale, or in the demand for capital goods of any kind depends on what is not consumed, but saved and productively expended. This is because consumption expenditure is merely consumption expenditure. It does not incorporate productive expenditure. The demand for goods at wholesale, for materials and machinery, and for labor by business is possible only to the extent that people do not consume but save and productively expend. Yet the Keynesians regard saving as a “leakage”and as allegedly diminishing the amount of subsequent incomes. [...] The Keynesian analysis explicitly argues that income is raised insofar as the additional incomes corresponding to the additional sales revenues are consumed, i.e., are not spent for business purposes, and that the rise in incomes will be the greater, the higher is the “marginal propensity to consume” and the lower is the “marginal propensity to save.”

[...] Samuelson and Nordhaus are utterly unaware that the overwhelmingly greater part of any income that could possibly be increased by virtue of the process they have described would be profit income. That is the only income that is earned on additional business sales revenue, and business sales revenue is the only receipt that private consumption spending generates (apart from some minor demand for domestic servants). It is also the only receipt that is generated by investment spending insofar as investment spending is for such things as the purchase of the lumber they assume in their example. Thus, for example, if I take $1,000 and go into a shopping mall and spend it in buying clothes, say, my expenditure is $1,000 of sales revenue to the seller of the clothes. The only income earned on those sales revenues is profit, not wages. (Readers who know anything about accounting should be sure to read the next paragraph.)

If the seller of the clothes then decides to consume $666.67 of his supposed $1,000 of additional income, say, by going elsewhere in the mall and buying dishes for that sum, then there is $666.67 of additional sales revenue to the seller of the dishes. Again, any additional income earned is profit, not wages. If the seller of the dishes, in turn, decides to consume $444.44 of his supposed additional income of $666.67, say, in buying shoes, then once again there is only additional business sales revenue, on which the only income that is earned is profit, not wages. In this case, carrying the process to n stages, the effect of the “multiplier” — if it actually existed — would be that the $1,000 of initial additional spending would bring about $3,000 almost entirely of additional sales revenues and hardly any additional wage income. If the additional sales revenues represented equivalent additional net income, the only additional net income they could represent would be profit income, not wages. The only additional wage income would be insofar as the original investment expenditure entailed the payment of wages as opposed to the purchase of capital goods. [29]

(In the interest of accuracy, I must point out that in reality, the amount of profit income earned on my $1,000 of expenditure would be less than $1,000 to the extent that the seller had to deduct additional cost of goods sold from his additional sales revenues. The incurrence of additional cost of goods sold, as I will show later on, represents disinvestment, and would actually work to undercut any actual net investment which might have launched the alleged spending chain. [30] In order for my $1,000 of expenditure to constitute $1,000 of additional profit income, we must assume that the seller sells exactly the same total physical volume of goods he otherwise would have sold in the accounting period, but now, thanks to my spending of this $1,000, he does so for $1,000 more of sales revenue. On this assumption, my expenditure of $1,000 would constitute an additional profit income of $1,000 to the seller. A similar assumption, of course, would have to be made for every subsequent round of spending.)

It is true that insofar as business sales revenues rise from year to year, on the foundation of a growing quantity of money and rising volume of spending, the greater portion of the additional sales revenues and accompanying profit incomes is spent by business firms in paying wages and in buying capital goods. But this is a productive expenditure, not a consumption expenditure. It is made out of the portion of the additional sales revenues and profits which are not consumed, but which are saved — something which, as I have said, the Keynesian analysis calls a “leakage,” and regards as unfortunate.

More on the Critique of the Multiplier

[...] That doctrine, it should be recalled, claims that a given increase in “investment” brings about a series of further increases in consumption, thereby resulting in an increase in national income that is a multiple of the original increase in investment. For example, with a “marginal propensity to consume” (viz., fraction of additional income consumed at each round) of .75, 10 of additional net investment is supposed to result in 30 of additional consumption and thus 40 of additional national income. [61]

[where sc = that part of total business sales revenues paid by consumers, i.e., paid not for the purpose of making subsequent sales; sb = that part of total business sales revenues paid by business firms, i.e., paid for the purpose of making subsequent sales; wc = that part of total wages paid by consumers, i.e., paid not for the purpose of making subsequent sales; and wb = that part of total wages paid by business, i.e., paid for the purpose of making subsequent sales.]

[...] Row 3, shows the alleged operation of the multiplier in the superficial terms in which the Keynesians propound it, that is, in terms merely of net investment and consumption. Thus, in the rightmost column, the table shows net investment increased by 10, that is, to 60 from the 50 of the second row. One column to the left, it also shows consumption increased by 30, that is, from the 550 of the second row to the 580 of the third row. On this basis, in the center column, the table dutifully shows national income and net national product increased from 600 to 640. Unlike the Keynesians, however, Row 3 shows on its left-hand side that the 40 of additional net national product and national income takes place specifically in the form of 40 of additional profit income and no additional wage income. This is a result that the highly superficial analysis of the Keynesians is unaware of and incapable of realizing. For the ability to recognize it depends on the use of the gross-national-revenue framework, which appears in the next three rows of the table.

Of those next three rows, the first two, that is, Rows 4 and 5, are reproduced exactly from Table 15–3. Only the last, Row 6 in the table, is new. It shows, in the rightmost column, that 10 of additional net investment comes about by virtue of 10 of additional sb, which rises from 500 in Row 5 of the table to 510 in Row 6. In raising total productive expenditure by 10, in the face of an unchanged magnitude of aggregate business costs, it results in 10 more of net investment. To be precise, total productive expenditure is elevated from the sum of 500 of sb plus 400 of wb, namely 900, to 510 of sb plus, once again, 400 of wb, namely to 910. In the face of the same aggregate business costs, d, of 850, the result is a rise in net investment from 50 to 60.

At the same time, of course, inasmuch as sb is not only a component of productive expenditure but also of business sales revenues, its new value of 510 must appear as sales revenues on the left-hand side of the Row 6. There its effect is to raise total sales revenues from 1,000, which is the sum of 500 of sc plus 500 of sb, to 1,010, which is the sum of 500 of sc plus, this time, 510 of sb. In the face of the same aggregate business costs, d, of 850, the result is a rise in aggregate profit from the 150 of Rows 2 and 5 to 160.

The rise in profits that is shown in Rows 3 and 6 is in fact much greater, namely, to 190 from 150. This is the result of the 30 of additional consumption spending that the multiplier doctrine alleges to occur on the basis of the 10 of additional net investment. The 30 of additional consumption spending constitutes 30 of additional business sales revenues, or at least something very close to 30 of additional business sales revenues. This is because the far greater part of private consumption spending is for goods and services of business firms, not for the labor of wage earners. For all practical purposes any additional demand for domestic servants can simply be disregarded.

Thus, on the right-hand side of Row 6, I show the rise in consumption as taking place entirely as a rise in sc from 500 to 530, which has the effect of raising total consumption from the sum of 500 of sc plus 50 of wc to 530 of sc plus 50 of wc, namely, from 550 to 580 of total consumption, C. At the same time, on the left-hand side of Row 6, the effect of the additional consumption is 30 more of business sales revenues and thus 30 more of aggregate profit. For business sales revenues are further increased from the sum of 500 of sc plus 510 of sb, to the sum of 530 of sc plus 510 of sb, that is, from 1,010 to 1,040. And because aggregate costs, d, remain at 850, the effect, as shown explicitly in Row 2 of the table, is to increase profits from 150 to 190.

It cannot be stressed too strongly that, consistent with the law of identity and the entire preceding discussion of this chapter, there is in this whole process absolutely no increase in the demand for labor by business or any further increase in the demand for capital goods subsequent to the initial 10 that gave rise to the increased net investment of 10. Furthermore, it should be realized that nothing essential is changed if we drop the assumption that all of the additional net investment is caused by arise in sb and assume instead that some of it results from additional wb. If for example, 5 of the initial 10 of net investment had come about in this way, once again followed by 30 of additional consumption, the only effect would have been that the rise in profits, instead of being all 40 of the rise in national income, would have been 35, and the rise in wages, instead of being zero, would have been 5. (That is, the rise in wages would have been the wages that might have been contained in the one possible act of productive expenditure present.) Contrary to the multiplier doctrine, any rise in the demand for labor or capital goods depends — it must be said once again — on what is not consumed, but saved and productively expended.

CHAPTER 16 THE NET-CONSUMPTION/NET-INVESTMENT THEORY OF PROFIT AND INTEREST

An Explanation of High Saving Rates Out of High Incomes

[...] For example, if the income of our hypothetical businessman or capitalist with $10,000,000 of capital rose from $500,000 to $1,000,000, his consumption would most likely rise only to something on the order of $525,000, while his provision for the future rose to something on the order of $10,475,000, for these sums stand in approximately the same respective proportions to $11,000,000 as do $500,000 and $10,000,000 to $10,500,000. Thus he would consume only about $25,000 of his additional income, and save all the rest of it. The percentage of his income that he saved would go from zero to almost 48 percent. In the same way, if the income he earned on his ten million of capital were $1,500,000, his consumption would rise to something on the order of $550,000 while his provision for the future rose to something on the order of $10,950,000. At this point, the percentage of his income that he saved would be over 60 percent.

This analysis helps to explain both why individuals with higher incomes tend to save larger fractions of their incomes than do those with lower incomes and, at the same time, why there is no tendency toward an ever rising proportion of saving out of income in the economic system as a whole, as the average level of real income rises. It is not the case that individuals having higher incomes save a larger portion of them than individuals having lower incomes, on the basis of any economic law pertaining to the absolute size of income. Rather it is the case that individuals with higher incomes are to a large extent businessmen or capitalists who earn a rate of profit that is higher than the rate of net consumption.

To the extent that this is the case, the income that is over and above what corresponds to the net-consumption rate counts merely as additional exchangeable wealth that is divided between consumption and provision for the future in essentially the same proportions as a lesser sum of exchangeable wealth consisting of capital plus its income. But this means that in the average case the only portion of the additional income that is consumed is a portion itself corresponding to the net-consumption rate, while all the rest goes to saving and provision for the future.

If these individuals were to earn the same amount of profit, however high that might be in absolute terms, and, at the same time, possessed a sufficiently larger amount of accumulated capital, they would consume the full amount of their high incomes. Let their accumulated capitals grow sufficiently relative to their incomes — in other words, let the rate of profit they earn fall to the net-consumption rate — and they will consume all of their income, however high it might be. For example, a businessman or capitalist with an income of $1,000,000 a year may well save half or more of it when his total accumulated capital is $10,000,000, but he would most likely consume all of a $1,000,000 income — and more — if his accumulated capital were $50,000,000, and most certainly if it were $100,000,000. In such a case, his saving out of income would be zero or less than zero. Indeed, on our present assumptions, he would consume all of a $1,000,000 income if his accumulated capital were just $20,000,000.

The fact that high rates of saving are to be found in connection with high rates of profit can also be explained on the basis of the fact that a high rate of saving out of a high rate of profit is the basis of building a fortune. Repeated compounding of the high rate of profit on a rapidly growing capital sum, whose rapid growth is made possible by a high rate of saving, results in the accumulation of a fortune. A high rate of profit provides both the incentive and the means for a high rate of saving, culminating in the possession of a fortune. [37]

As previously noted, apart from the connections between high rates of profit and high rates of saving out of income, Milton Friedman has shown the vital role played by expectations concerning permanent or long-run average income in leading individuals to save heavily in periods when their income temporarily exceeds their expectations of this kind. Thus, individuals such as best-selling novelists, prominent athletes, and movie stars, whose incomes in an individual year or limited period of years are among the highest in the economic system, often save heavily. The reason they do so is not because their incomes are high absolutely or relative to those of the average member of the economic system, but because their incomes are high relative to their own expected long-run average incomes and thus need to be saved heavily to make possible a more even level of consumption over time. [38]

Friedman’s insight helps to explain high saving out of profits in a context in which the high rate of profit cannot be expected to continue. In this case, the profits must be heavily saved if the individual is to benefit from them in the years when his profit income will be lower, owing to the prospective fall in the rate of profit he will earn.

[...] If the owner of a capital of $10,000,000, wishes to provide for his wants over a period of twenty years, say, and to do so evenly, then the most he will wish to consume in the present year is $500,000. If he earns no income this year, then his capital falls by that amount. In succeeding years, if he continues to earn no income, he may go on consuming $500,000 a year until his capital runs out, or if his “time horizon,” so to speak, remains constant at twenty years, he will progressively diminish his consumption as his capital declines, keeping it at a constant one-twentieth of the declining amount. [39]

The present discussion makes it clear that the high rates of saving that take place out of the high incomes existing at any given time are not the result of the absolute height of those incomes. They are the result of the height of those incomes relative to accumulated capital or to the expected long-run average income of the individuals. Where high incomes are not earned as a high rate of profit on capital and are not perceived as higher than one’s long-run average income, they are not accompanied by high rates of saving. That is to say, where they are earned in the form of a low rate of profit on a large sum of capital or where they are earned in the form of high wages which are expected to continue to be earned over the rest of one’s life, the high incomes are not accompanied by high rates of saving. The businessman or capitalist with a large amount of capital relative to his income need not save, because he can look to his existing capital to provide for his future wants even if he consumes an amount equal to the whole or even somewhat more than the whole of his modest rate of profit. A wage earner who can expect to earn a high wage income throughout his life can look to his future wages as the means of providing for his future consumption. It is not necessary for him to make provision for the future beyond providing for old age and other possible periods of incapacity, and for the purchase of goods that are too expensive to be purchased out of current income.

When these facts are understood, it becomes possible to explain such things as why the average American of today does not save a larger proportion of his income than did his grandparents, even though in real terms as well as in monetary terms his income is far greater than theirs was. As has just been shown, the explanation is that higher real income as such, that is, by itself, does not cause a higher rate of saving. Indeed, owing to changes in political conditions that affect the general security of property, such as the tax system and the monetary system, and to changes in cultural values that are philosophical corollaries of the political changes, today’s generation of Americans saves less relative to its income than was the case in the past, even though, for the time being at least, real incomes continue to be far higher than in the past. Confiscatory taxation, fiat money and inflation, and the decline of the sense of individual responsibility have all worked to reduce the degree of provision for the future relative to current consumption and thus to reduce saving out of income, despite the fact that real incomes continue at a level far higher than prevailed in the past and, at least until relatively recently, had even continued to rise. The slower rate of increase in real income that is the result of these causes is also a major cause of the reduced rate of saving out of income. This is implicit in the preceding discussion. [40]

Indeed, to maintain that individuals with higher incomes by that very fact tend to save relatively more than individuals with lower incomes, is to reverse cause and effect. This is because it is not high income as such which is the cause of high saving, but high saving which is the cause of high income, both absolutely and relatively. … high saving and the high relative demand for capital goods that it makes possible is the cause of high and rising real income in that it is a leading cause of capital accumulation, rising production, and falling prices, which progressively increase the buying power of given money incomes. [...]

4. Net Investment as a Determinant of Aggregate Profit and the Average Rate of Profit

The equality between profits and net consumption rests on an equality between productive expenditure and the costs deducted from sales revenues in business income statements. In such circumstances, an excess of sales revenues over costs is possible only to the extent that there is an excess of sales revenues over productive expenditure. As we have seen, since both sales revenues and productive expenditure embrace the demand for capital goods, an excess of sales revenues over productive expenditure rests on an excess of receipts from the sale of consumers’ goods over the demand for labor by business, that is, on net consumption. As we know, net consumption in turn is the result of the consumption expenditure of businessmen and capitalists, financed out of dividend, draw, and interest payments.

However, productive expenditure and costs need not be equal. For reasons I will explain, productive expenditure is usually greater than costs, and sometimes it is less. In these circumstances, net investment, positive or negative, exists. And at such times, the amount of profit in the economic system turns out to equal the sum of net consumption plus net investment.

Figures 16–1 and 16–2 and Tables 16–3 and 16–4 exemplify the fundamental distinction that exists between productive expenditure and costs. In these figures and tables, the productive expenditure of any given year shows up as costs deducted from sales revenues in the following year. By the same token, the costs of any given year are shown as representing the productive expenditure of the year before. Such a fundamental distinction of timing, whether of years, months, or weeks, usually exists between productive expenditure and the costs it generates in business income statements. In essence, today’s productive expenditures for the most part show up as costs in the future, while today’s costs for the most part reflect productive expenditures made in the past.

The distinction between productive expenditure and costs was explained in detail in Chapter 15. There it was shown that all of productive expenditure which is for plant and equipment or inventory and work in progress, is added to asset accounts, while the corresponding items of cost, namely, depreciation and cost of goods sold, which reflect previous productive expenditures, are subtracted from those asset accounts. On this basis, the difference between productive expenditure and costs in the economic system was shown to constitute net investment, that is, the net change in the value of those asset accounts. [47, see pp. 702–705]

The continuous equality between productive expenditure and the costs deducted from sales revenues that is found in Figures 16–1 and 16–2 and in Tables 16–3 and 16–4 is the result of nothing more than the assumption that productive expenditure is the same year after year, reinforced by the further assumption that all productive expenditure shows up as costs precisely one year later. Under these assumptions, productive expenditure and costs show up as the same in amount year after year, to the end of time.

Nevertheless, if one looks at Table 16–5, one can observe an important break in the equality between productive expenditure and costs, and, at the same time, an equivalent break in the equality between profits and net consumption. Specifically, one will observe in Year 2 of Table 16–5 that productive expenditure exceeds costs by 100, and, at the same time, that profits exceed net consumption by 100. For in that year, while productive expenditure is 900, costs are only 800, and while net consumption is only 100, profits in the economic system are 200.

Table 16–5 is very similar to Table 16–3. Its only essential difference is that in Year 2 it introduces a rise in productive expenditure from 800 to 900 monetary units, which is made possible by an equivalent fall in net consumption from 200 to 100 monetary units. [48] In all subsequent years, 900 and 100 monetary units remain the respective magnitudes of productive expenditure and net consumption. Total sales revenues, of course, continue at 1,000 monetary units throughout, inasmuch as 100 monetary units of additional demand for the products of business generated by productive expenditure take the place of the 100 monetary units of reduced demand for the products of business coming from the consumption of businessmen and capitalists, viz., from net consumption. [49] What Table 16–5 shows is that even though productive expenditure in Year 2 rises from 800 to 900, costs continue to be 800, reflecting the fact that productive expenditure in Year 1 was 800. Only from Year 3 on do costs rise to the higher level of productive expenditure.

[49] It should be realized that from the point of view of the magnitude of sales revenues, it is indifferent whether the 100 of additional demand generated by productive expenditure represents 100 of additional demand for capital goods or 100 of additional demand for labor by business resulting in 100 of additional demand for consumers’ goods by the wage earners of business, or any combination of such additional demands for the products of business totaling 100.

Because of this lag in the rise in costs to reflect the rise in productive expenditure, profits in Year 2 continue to equal 200, despite the fall in net consumption to 100. This is the case inasmuch as sales revenues remain at 1,000 while costs remain at 800. All that has happened so far in Table 16–5 is that net consumption — the demand for consumers’ goods by businessmen and capitalists — is down and productive expenditure and the demand for capital goods and/or the demand for producers’ labor and producers’ labor’s demand for consumers’ goods are up by just as much. Thus, there is no change in aggregate sales revenues and, as yet, no change in aggregate costs. As a result, profits are as yet unchanged, despite the fall in net consumption.

The unmistakable and obvious implication of this inequality between profits and net consumption is that something else, besides net consumption, determines the amount of profit in the economic system. That something else, of course, turns out to be nothing other than net investment. This is because the excess of profits over net consumption is the excess of productive expenditure over costs. Profits remain the same rather than fall to an amount equal to the smaller amount of net consumption, because, while sales revenues remain the same, costs have not yet risen to equal the larger amount of productive expenditure that the smaller amount of net consumption makes possible. If costs did equal the larger productive expenditure, profits would equal sales revenues minus the larger productive expenditure, that is, they would equal the smaller net consumption. So long as costs fall short of the larger productive expenditure, profits exceed the smaller net consumption. This shortfall of costs relative to productive expenditure, or, equivalently, this excess of productive expenditure over costs, is, as we know, net investment. For productive expenditure comprises debits or pluses to the assets of business, while costs comprise credits or minuses to those assets. Thus, to the extent that productive expenditure exceeds costs, the pluses to the assets of business exceed the minuses from those assets, with the result that there is an equivalent net change in the book value of those assets — viz., there is equivalent net investment.

In connection with this last point, it is necessary to keep in mind specifically that productive expenditure incorporates business spending on account of plant and equipment and inventory and work in progress, which represents debits or pluses to these respective asset accounts, while costs include depreciation and cost of goods sold, which represent credits or minuses to these respective asset accounts. The difference is net investment in plant and equipment plus net investment in inventory and work in progress. Insofar as productive expenditure and costs do not comprise such pluses or minuses to assets, they represent identically equal expensed expenditures, that is, items that are not debited to any asset account, but written off — expensed — as made. Such items — for example, many advertising and research and development outlays — are simultaneously productive expenditures and costs. The subtraction of such costs from such productive expenditures nets to zero and thus leaves undisturbed the fact that total productive expenditure minus total costs equals net investment. [50, see pp. 702–705]

The relationship between profits and net investment is actually very simple. Net investment is productive expenditure minus costs. Profit is sales revenues minus those same costs. The great bulk of sales revenues, moreover, is generated by and is equal to productive expenditure. Productive expenditure, recall, embraces the demand for capital goods, which at the same time literally is a major component of sales revenues. Furthermore, productive expenditure embraces all the wage payments by business firms, which is the source of the far greater part of receipts from the sale of consumers’ goods by business. Thus, to the extent that productive expenditure exceeds costs and produces corresponding net investment, the sales revenues generated by and equal to productive expenditure exceed those same costs and thus result in profits equal to the net investment. Once again, the existence of net investment means that productive expenditure exceeds costs. At the same time, it means that the portion of business sales revenues generated by and equal to productive expenditure exceeds those same costs, and thus that profit exists at least to the same extent as net investment exists. Indeed, the only thing that prevents a perfect identity between profits and net investment is the extent to which sales revenues exceed productive expenditure, that is, the extent to which net consumption exists.

Table 16–6 illustrates the effect of net investment on profits by incorporating the data from Year 2 of Table 16–5 into a framework similar to that of Table 16–2, which set forth the role of net consumption in making possible an excess of the demand for the products of business over the demand for factors of production by business, that is, of sales revenues over productive expenditure. The table shows that aggregate profit in the economic system equals the sum of net investment plus net consumption. It does so by showing once again the demand for factors of production by business (productive expenditure) on the left and the demand for the products of business (sales revenues) on the right. It shows total sales revenues generated equal to the sum of productive expenditure plus net consumption: specifically, sales revenues of 900 generated by productive expenditure and sales revenues of 100 generated by net consumption.

The 900 of sales revenues generated by productive expenditure are 600 of receipts from the sale of capital goods plus 300 of receipts from the sale of consumers’ goods to wage earners. The 600 of receipts from the sale of capital goods, of course, are identically equal to the component of productive expenditure representing the demand for capital goods. The 300 of receipts from the sale of consumers’ goods to wage earners are quantitatively equal to the component of productive expenditure representing the demand for labor. The 100 of sales receipts generated by the sale of consumers’ goods to businessmen and capitalists are the receipts representing net consumption. Total sales revenues in Table 16–6, of course, equal 1,000, with 600 representing demand for capital goods and 400 the total demand for consumers’ goods coming both from businessmen and capitalists and from wage earners, together.

Now the deduction of 800 of costs from 900 of productive expenditure on the left-hand side of Table 16–6 results in net investment of 100. When those same costs are deducted on the right-hand side of Table 16–6 from the 900 of sales revenues generated by the 900 of productive expenditure, the result is 100 of profits corresponding to the 100 of net investment. Total profits, of course, are 200, rather than 100, because total sales revenues are 1,000, not 900. Sales revenues are generated by the sum of productive expenditure plus net consumption, not by productive expenditure alone. When the 800 of costs are deducted from this larger total of sales revenues, the total amount of profit surpasses net investment by the amount by which total sales revenues surpass the portion of sales revenues generated by productive expenditure alone, that is, by the amount of sales revenues generated by net consumption.

Perhaps the simplest way to think of the equality between profits and the sum of net consumption plus net investment is in terms of the following relationships:

(1) profits = sales – costs. (2) profits = sales – productive expenditure + productive expenditure – costs. (3) sales – productive expenditure = net consumption. (4) productive expenditure – costs = net investment.

Thus, substituting equations (3) and (4) into equation (2) we obtain:

(5) profits = net consumption + net investment.

In other words, profits are sales minus costs. They are also sales minus productive expenditure plus productive expenditure minus costs. Inasmuch as both sales revenues and productive expenditure contain the demand for capital goods, sales revenues minus productive expenditure reduces to the demand for consumers’ goods minus the demand for labor, that is, to net consumption. Inasmuch as productive expenditure represents pluses to assets, while costs represent minuses to assets, productive expenditure minus costs is net investment. Thus, profits equal net consumption plus net investment.

Table 16–7 further illustrates the relationship between net investment and aggregate profit by showing a variety of possible cost values and the corresponding effects on net investment and profits together. The table assumes that productive expenditure is constant at 800 and that net consumption is constant at 200, with the result that sales revenues in the economic system are constant at 1,000. For purposes of illustration, three different values for aggregate costs are assumed: 800, 700, and 900, labeled (1), (2), and (3) respectively. Under these assumptions, when costs are 800, that is, equal to productive expenditure and to the sales revenues generated by productive expenditure, both net investment and the profits corresponding to net investment are zero. Thus, total profits equal 200, which is the amount by which sales revenues exceed productive expenditure and the costs equivalent to productive expenditure. That is, in this case, profits equal net consumption alone. All of these results are indicated by the label (1). When costs are 700 in the face of the 800 of productive expenditure and the 800 of sales revenues generated by productive expenditure, net investment is 100 and the profits corresponding to net investment are 100. Thus, in this case, total profits equal 300 — the sum of the 200 of net consumption plus the 100 of net investment. In other words, they are now equal to the sum of the amount by which sales revenues exceed productive expenditure plus the amount by which productive expenditure exceeds costs. These results are indicated by the label (2). When costs are 900, net investment is minus 100 and profits altogether are 100, equal to the sum of the 200 of net consumption plus the minus 100 of net investment. In this case, profit is equal to the sum of the excess of sales revenues over productive expenditure less the excess of costs over productive expenditure. These results are indicated by the label (3).

As we have seen, the variation of profits with net investment is produced by the fact that net investment exists to the degree that productive expenditure is greater than costs. But since productive expenditure is directly or indirectly the source of equivalent sales revenues, any excess of productive expenditure over costs is accompanied by a precisely equivalent excess of sales revenues over those same costs, which excess represents precisely equivalent profits. That is, to whatever extent productive expenditure exceeds costs and generates net investment, the sales revenues generated by productive expenditure, and equal to productive expenditure, exceed those same costs and generate profit. Thus, to the extent that net investment is positive, and the portion of sales revenues generated by productive expenditure exceeds costs, the excess of total sales revenues over costs is equivalently enlarged and profits exceed net consumption by the amount of net investment. By the same token, to the extent that net investment is negative, and the portion of sales revenues generated by productive expenditure falls short of costs, the total of sales revenues exceeds costs by less than the amount of net consumption; that is, profits are reduced by the amount of negative net investment.

It may be helpful to think of matters this way: while net investment — the excess of productive expenditure over costs — represents an equivalent excess of the part of sales revenues generated by productive expenditure, and equal to productive expenditure, over those same costs, net consumption represents a further excess of sales revenues over costs — the excess of sales revenues over productive expenditure itself. By the same token, while net consumption would generate profits even if costs equalled productive expenditure, the existence of net investment means that costs are equivalently less than productive expenditure and equivalently less than the portion of sales revenues generated by and equal to productive expenditure, and thus that profits exceed net consumption by the amount of net investment.

Under the assumptions we have been making of an invariable money [i.e., money of invariable value, see pp. 536-540] and that all the capital goods and labor of any given year are used up in producing the products just of the next year, net investment is necessarily of short duration. Under such conditions, it can exist only on the strength of a rise in productive expenditure founded on a fall in net consumption, and then it can last only for a single year, before costs rise to equal the higher level of productive expenditure. This is the situation in Year 2 of Table 16–5. As we shall soon see, however, in the absence of these assumptions, in particular the assumption of an invariable money, net investment can exist not only as a long-standing, indeed, permanent source of aggregate profit, but also with no tendency toward diminution in its quantitative importance relative to that of net consumption.

Now it follows that since the aggregate amount of profit in the economic system is equal to the sum of net consumption plus net investment, that the average rate of profit in the economic system equals not only the previously described net-consumption rate, but the sum of the net-consumption rate plus the net-investment rate. This is merely to say, that in equalling the amount of net consumption plus the amount of net investment, all divided by the amount of capital invested, the average rate of profit equals the amount of net consumption separately divided by the amount of capital invested (the net-consumption rate) plus the amount of net investment separately divided by the amount of capital invested (the net-investment rate). This is on the elementary algebraic principle that (a+b)/c = a/c + b/c. In other words, the average rate of profit in the economic system can be expressed as equal to and determined by the rate of net consumption plus the rate of net investment. This formula is of great importance, and I will refer to it repeatedly in subsequent discussion.

CHAPTER 18 KEYNESIANISM: A CRITIQUE

2. The Unemployment-Equilibrium Doctrine and Its Basis: The IS Curve and Its Elements

These twists and turns concern how Keynesianism arrives at the notion of a fixed aggregate quantity of goods and labor demanded. One route is the widely held belief, fostered by labor unions, that because a cut in wage rates reduces the ability of the individual wage earner to spend money for consumers’ goods, it correspondingly reduces overall spending for consumers’ goods in the economic system. This is an elementary fallacy. It does not see that the reduction in wage rates makes possible the employment of correspondingly more wage earners, with the result that the total amount of spending — the monetary demand — for consumers’ goods does not fall. The basic result is the existence of the same amount of monetary demand both for labor and for consumers’ goods, but because wage rates and prices are lower, the same respective monetary demands employ more labor and buy more consumers’ goods. [18]

Of course, the demand for labor and the wage earners’ demand for consumers’ goods are not the only relevant monetary demands in the economic system. There is also the demand for capital goods and the demand for consumers’ goods on the part of businessmen and capitalists, i.e., net consumption. It is entirely possible that under an invariable money [i.e., money of invariable value], a fall in wage rates would be accompanied by some change in the demand for labor accompanied by an equal and opposite change in one of these other elements, especially in the demand for capital goods. But even if this entailed some fall in the aggregate monetary demand for labor, over and against this is the fact that in the context of the elimination of mass unemployment the fall in wage rates to their new equilibrium level almost certainly results in a rise in spending of virtually all kinds, including the demand for labor. This is because in a situation of mass unemployment the fall in wage rates brings out the investment expenditures which had been postponed, awaiting their fall. Thus, in actuality, the fall in wage rates to their new equilibrium is accompanied by a rise in the aggregate monetary demands for labor and for goods, both consumers’ goods and capital goods. [19]

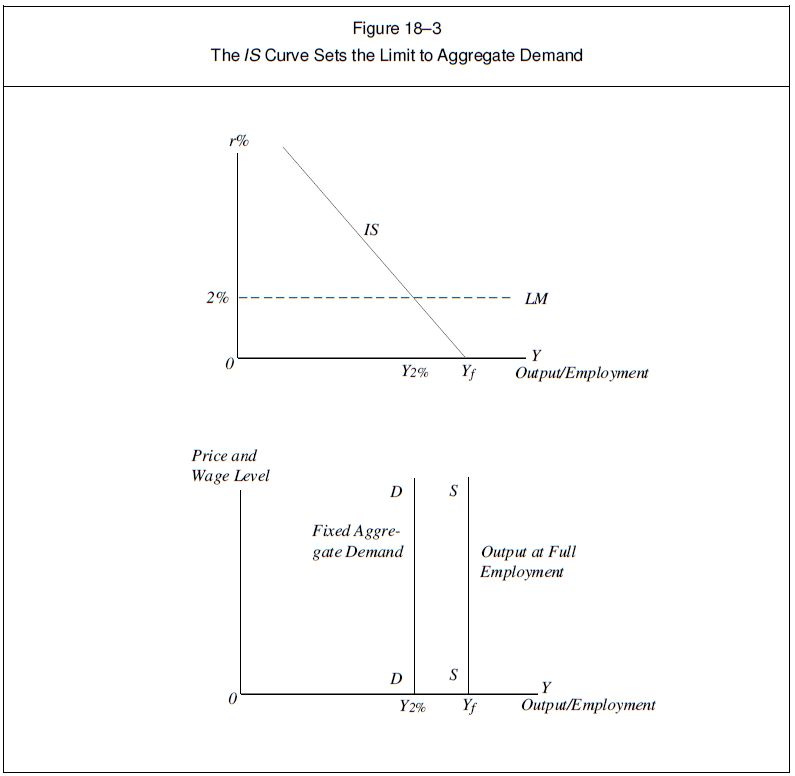

… The IS curve is the relationship between the “marginal efficiency of capital” (viz., the rate of profit and interest), on the one side, and the volume of output and employment, on the other, for equilibria of investment and saving. (The meaning of this definition will become clearer as we proceed.) The IS curve purports to show that as output and employment expand, as measured along the horizontal axis, the rate of return on capital falls, as measured along the vertical axis. (Output is represented by Y and the rate of return is represented by r.) The Keynesians claim that at the point of full employment, namely Yf and its corresponding output, the rate of return would either be negative or, if not negative, at least unacceptably low — below 2 percent is the usual estimate of what is unacceptably low. [21] This alleged insufficiency of the rate of return that would exist if full employment were achieved is supposed to be the reason that full employment cannot exist, or if it did exist, could not be maintained.

Observe that in Figure 18–2 full employment and the output it results in are alleged to be accompanied by a rate of return on capital of zero. The specific assumption of a zero rate of return is not necessary. Any rate of return on capital of less than 2 percent is held to be unacceptably low. At any such rate of return, the Keynesians argue, businessmen and investors will prefer to hoard cash rather than to invest. Thus, if full employment requires any rate of return below 2 percent, the existence of full employment is allegedly impossible, at least as a lasting phenomenon. And this, according to the Keynesians, is exactly what it does require and is why its existence is allegedly impossible. Full employment cannot exist under the conditions of modern capitalism, say the Keynesians, because its existence requires a rate of return on capital below the minimum acceptable rate of 2 percent, the rate below which lending and investing allegedly simply do not pay. Whether full employment actually requires a rate of return of zero, 1 percent, 1 ½ percent, or a negative rate of return, the rate is allegedly just too low to make investment worthwhile. And thus, if somehow full employment were achieved, say the Keynesians, savings would be hoarded rather than invested. The effect would be a drop in spending for output and labor and a reduction in output and employment below the full-employment level. This would go on until sufficient movement had taken place up and to the left along the IS curve to raise the rate of return on capital back up to the 2 percent figure, the alleged minimum acceptable rate of return. [...]

Figure 18–3, which combines the IS curve of Figure 18–2 with the aggregate demand and supply curves of Figure 18–1, shows precisely how the IS curve is supposed to set the allegedly fixed limit of aggregate demand. [23] The horizontal axes of both diagrams are exactly the same. In the upper diagram, depicting the IS curve, output and employment are limited to the point marked Y2%. This is because that is the volume of output and employment at which the rate of return on capital is 2 percent. Any greater volume of output and employment would allegedly require a rate of return below 2 percent, which is unacceptably low and which would induce the hoarding of savings and drive the volume of output and employment back down (viz., to the left) and the rate of return back up. Equilibrium would allegedly be reached only at the respective values of Y2% for output and 2% for the rate of return. This is the situation with respect to the IS curve, in the upper diagram of Figure 18–3.

The vertical aggregate demand curve DD, in the lower diagram of Figure 18–3, is drawn precisely at the point where the volume of output and employment allegedly bring the rate of return on capital on the IS curve down to 2 percent. DD cannot be one iota to the right of where it is, say the Keynesians, because if it were, the rate of return on capital invested would be below the minimum acceptable rate of 2 percent on the IS curve shown in the upper diagram. Thus, say the Keynesians, the aggregate demand curve of Figure 18–3 cannot possibly move to the right to coincide with the aggregate supply curve that reflects output at the point of full employment. It cannot, it is argued, because, if it did, the rate of return on capital would be zero, as shown by the IS curve in the upper diagram, at the point of output corresponding to full employment. Indeed, the aggregate demand curve allegedly cannot move so much as a hair’s breadth to the right without reducing the rate of return below the minimum acceptable level, as shown by the position of the rate of return on the IS curve.

Thus the Keynesian argument is that full employment cannot exist, because if, somehow, it did, the rate of profit would be too low. Businessmen would then start to hoard, and the hoarding would reduce output and employment until the rate of profit was raised back up to an acceptable level. This is supposed to be the reason why a fall in wage rates and prices is unable to achieve full employment.

The underlying problem, allegedly, is that the physical output corresponding to full employment imposes an unacceptably low rate of return on capital. The level of wage rates and prices is thus held to be irrelevant. Employment and output cannot get beyond where they are, no matter what happens to wage rates and prices, according to the Keynesians, because if they did, the rate of return on capital would be lower than it is, which is already the minimum acceptable rate. Thus, say the Keynesians, the only effect of a fall in wage rates and prices would be a reduction in the volume of spending for the same amount of goods and labor, not any increase in employment and output. [...]

In order to accomplish this, it is necessary to explain the process by which the Keynesians derive the IS curve from various other real or imagined relationships. These relationships are: (1) the production function, (2) the saving function, (3) an equality of saving and investment, and (4) the marginal-efficiency-of-capital schedule. All of them, and the derivation of the IS curve from them, are shown in Figure 18–4 as a set of five interconnected diagrams. The production function appears in the diagram in the bottom-left portion of Figure 18–4; the saving function, in the diagram in the top-left portion; the equality of saving and investment, in the diagram in the top-right portion; the marginal efficiency of capital schedule, in the diagram in the center-right portion of the figure; and, finally, the IS curve, in the diagram in the center-left portion of the figure.

“Production function,” it should be recalled from Chapter 13, is simply the technical name given to the relationship between the volume of employment (labor performed) and the volume of output that results, given the state of technology and the supply of capital equipment. The labor performed is shown on the vertical axis, while the output produced is shown on the horizontal axis. This, of course, is a relationship that is in no way specific to Keynesian economics. [24, see Fig. 13–1, on p. 545] The use of the letter N, however, to measure the volume of employment is taken from the practice of the Keynesian textbooks.

The “saving function” is the Keynesian doctrine that a definite, determinate mathematical relationship exists between the level of income, on the one side, and the volume of saving out of income, on the other. In the diagram, saving is shown on the vertical axis and income on the horizontal axis. The saving function is the corollary of the more widely known Keynesian doctrine of the “consumption function,” according to which consumption spending is mathematically determined by the level of income. It is derived by subtracting the consumption function from income. Typically, it is presented as the algebraic formula

S = –a + (1–c)Y,

where a is a given amount of consumption that occurs irrespective of the level of income, c is the “marginal propensity to consume,” viz., the extra consumption that take place out of additional income, and Y is national income/net national product. A minus sign appears before the constant a to indicate the amount of dissaving that would occur if income were zero. Since all income is either consumed or saved, and c is the marginal propensity of consume, 1-c is the “marginal propensity to save.”

It should be noted that there is more than a little equivocation in the way the symbol Y is used. When it appears in connection with the production function, it refers to physical output — to “real income.” When it appears in connection with saving, however, it becomes money income, out of which cash hoarding occurs. Please note in this connection that the horizontal axis of the production function and the saving function are presented as identical, and so is the horizontal axis of the IS curve. Y is the measure of all three.

The third diagram — the equilibria of saving and investment — in the upper-right portion of Figure 18–4, shows investment equal to saving at every point. The vertical axis of this diagram is identical with the vertical axis of the saving-function diagram. Thus it too represents saving. The equality of investment, which is shown on the horizontal axis, with saving, is accomplished by the drawing of a 45-degree line through the origin. Every point on this line represents an equal distance on both axes of the diagram, and thus represents an equality of saving and investment. The purpose of this diagram is to set the stage for showing why investment cannot in fact be equal to saving when saving is substantial. Its purpose is to ask what would happen if all that were saved at every level of real income were actually invested.

The answer to this last, and very critical question is supposedly supplied in the fourth diagram, the marginal-efficiency-of-capital schedule — mec schedule for short — in the center-right portion of Figure 18–4. Here, the horizontal, investment axis of the diagram above is repeated, while the rate of return on capital is shown on the vertical axis. It is claimed that the greater is the volume of net investment, the lower is the rate of return on capital. This is shown by the mec schedule sloping downward to the right, with the greater being the size of I, the smaller being the size of r. (The reasons advanced in support of the mec doctrine will be presented shortly. For the moment, it can be taken at face value, simply in order to understand the derivation of the IS curve. It is important to note in this connection, that the vertical axis of the mec schedule and the vertical axis of the IS curve are also identical.)

Given the production function, the saving function, the equilibria of saving and investment, and the mec schedule, the derivation of the IS curve is not difficult. We can begin by picking a low level of employment. Let us take point N0 on the vertical axis in the bottom-left diagram. Reading over to the production function, along the dashed line, we see that this implies a definite level of output (real income). Call that level of output Y0. Now we read up a dashed line, all the way to the saving function. There, we find that Y0 output (income) implies S0 of saving. Reading across, along the dashed line, to the investment-equals-saving diagram, we find that S0 of saving requires I0 of net investment, if the saving is not to be hoarded. Reading down now, along the dashed line to the mec schedule, we find that I0 of net investment implies an r0 rate of return. If we now connect the Y0 output produced by the N0 volume of employment, with the r0 rate of return that results from the investment of the savings generated by that level of output (income), we have a point on the IS curve.

Down in the bottom-left diagram, let us pick a second, higher level of employment on the vertical axis, namely, the amount denoted by N1. Reading over to the production function, we see that this implies another definite level of output — a higher one. Call it Y1. Again, we read up along the dashed line to the saving function. There we find a second, higher level of saving. Call it S1. Reading across to the saving-equals-investment diagram, we find that S1 of saving requires equivalent I1 of investment, if the saving is not to be hoarded. Reading down to the mec schedule, we find that I1 of investment implies a lower, r1 rate of return. If we now connect the r1 rate of return with the Y1 level of output, we obtain a second point on the IS curve. This is a point of greater output and a lower rate of return. What is present here is that more employment means more output (real income), more saving, the need for more investment to prevent the hoarding of that saving, and a lower rate of return on investment, if that investment actually takes place.

Finally, let us pick a third, still higher level of employment on the vertical axis in the production-function diagram. Let us call it “full employment, and denote it by the letters Nf. Once more reading over to the production function along a dashed line, we find that the higher level of employment goes with a higher level of output. Call this level of output Yf, the full-employment level of output. Reading up along the dashed line to the saving function, we see that there is a higher level of saving corresponding to the full-employment level of output. Call it Sf, the full-employment level of saving. Reading over to the saving-equals-investment diagram, we see that Sf of saving, if it is not to be hoarded, requires the correspondingly larger amount If of net investment. Reading down to the mec schedule, we see that If of net investment is accompanied by a further reduction in the rate of return to rf, the full employment rate of return. The rf rate of return and the Yf level of output constitute a third point on the IS curve. Unfortunately, say the Keynesians, this rate of return is simply below the minimum acceptable rate of return of 2 percent, and so full employment cannot be achieved, or if somehow achieved, cannot be maintained.

A fall in wage rates and prices is held to be useless in achieving full employment because all of the above relationships are supposed to hold true in physical terms. Nf of employment means Yf of output, means Sf of saving, requiring If of net investment, which causes too low a rate of return. These same physical relationships allegedly hold irrespective of the wage-and-price level. Specifically, at a lower wage-and-price level, it is held, no more physical investment is profitable (yields more than 2 percent) than before.

If, for example, initially there is 250 of investment at a 2 percent rate of return and, say, approximately 10 percent unemployment, a fall in wage rates and prices to 9⁄10 their initial level will not achieve full employment — indeed, it will supposedly not achieve any increase in employment at all. This is because investment will allegedly have to fall 10 percent to 225 — that is, in full proportion to the fall in wage rates and prices. It is claimed that investment must fall in this way because all the investment that there is room for at a 2-percent-or-greater rate of return is, allegedly, that physical amount of investment — for example, so many steel mills, cement factories, bicycle shops, and so forth — which at the initial price-and-wage level requires 250 to purchase. At a price-and-wage level 9⁄10 as high, that physical amount of net investment requires only 225 to purchase. Net investment cannot remain at 250 in money, because then 250 of monetary net investment would be equivalent to approximately 278 of net investment at the initial price-and-wage level (viz., at 9⁄10 times the initial price-and-wage level, 250 would be equivalent in buying power to 10⁄9 times 250, which is 278). This greater physical amount of net investment would mean a rate of return below 2 percent. Thus, all that net investment can be at the 9⁄10 price-and-wage level is 225, because now 225 represents the alleged maximum physical quantity of net investment that is profitable.

In exactly the same way, if the wage-and-price level were to fall all the way to half, the monetary amount of net investment would supposedly have to fall in half — to 125 from 250. It allegedly could not remain at 250 or even at 225, because monetary amounts of net investment at those levels would now represent real, physical net investment equivalent to what 500 purchased at the initial price-and-wage level, or what 450 would purchase at 9⁄10 the initial price-and-wage level. Such volumes of net investment would allegedly thus result in a rate of return all the more below 2 percent. At a halved wage-and-price level, net investment cannot get beyond 125 in money, it is held, because that sum now represents the maximum physical amount of net investment that is profitable. [25]

These results are shown in Figure 18–5. Below the horizontal axis in this figure are three different scales of measurement of net investment, each one corresponding to a different price-and-wage level, namely, the initial price-and-wage level, one that is 9⁄10 as high, and one that is only half as high. Because the same maximum physical amount of net investment is allegedly all that is profitable — namely, the amount that is profitable down to a rate of return of 2 percent and no lower — the effect is that each successive scale of measurement at lower prices and wages moves correspondingly to the right. Thus, the net investment that initially required 250 to purchase, successively requires only 225, and then only 125. Continued net investment in the amount of 250 at the 9⁄10 price-and-wage level, and then at the halved price-and-wage level, would allegedly result in rates of return on capital respectively equivalent to those produced by 278 and 500 of net investment at the initial price-and-wage level.

Thus, despite the fall in wage rates and prices, the problem that allegedly remains is that there cannot be an outlet for saving in excess of the given physical amount of net investment that is profitable (i.e., that yields 2 percent or more). And thus there cannot be a real income (output) that results in any such greater level of saving, nor, finally, a volume of employment that would result in any such level of output. The volume of employment is thus allegedly limited to that amount that results in a level of output (real income) out of which saving is no greater than is consistent with the allegedly limited physical volume of profitable investment opportunities.

In other words, according to the Keynesians, there cannot lastingly be a level of employment, output, and real income greater than what produces the limited volume of saving that can be accommodated by the limited volume of profitable investment opportunities. If the volume of employment is greater than the one that produces such a limited level of saving, then saving supposedly exceeds the limited profitable investment opportunities that exist, thereby driving the rate of return on capital below the minimum acceptable level. The alleged consequences are that hoarding results, spending drops, and sales revenues, employment, and output all decline. Their decline then represents a drop in real income. Out of the smaller real income, less saving occurs. The drop in employment, output, and real income must allegedly be great enough to reduce the volume of saving to the point where it no longer exceeds the allegedly limited profitable investment opportunities available.

In sum, full employment, or any employment beyond a fixed, given amount, cannot exist, or at least cannot be maintained, according to the Keynesians, because it would produce a physical volume of output out of which there would be a physical volume of saving requiring a physical volume of net investment that would put the rate of return below the minimum acceptable rate. In essence, the Keynesian argument is that full employment cannot exist in a free economy because if it did, the economic system would, in effect, choke on the allegedly excessive saving that would accompany full employment. Keynes himself states the essence of his position in the following words (where helpful, I insert my own clarifications in brackets):

Perhaps it will help to rebut the crude conclusion that a reduction in money-wages will increase employment “because it reduces the cost of production”, if we follow up the course of events on the hypothesis most favourable to this view, namely that at the outset entrepreneurs expect the reduction in money-wages to have this effect. It is indeed not unlikely that the individual entrepreneur, seeing his own costs reduced, will overlook at the outset the repercussions on the demand for his product and will act on the assumption that he will be able to sell at a profit a larger output than before. If, then, entrepreneurs generally act on this expectation, will they in fact succeed in increasing their profits? Only if the community’s marginal propensity to consume is equal to unity, so that there is no gap between the increment of income and the increment of consumption [i.e., there is no additional saving]; or if there is an increase in investment, corresponding to the gap between the increment of income and the increment of consumption, which will only occur if the schedule of marginal efficiencies of capital has increased relatively to the rate of interest [i.e., either the mec schedule must somehow move to the right, which there is allegedly no reason for its doing, or the rate of interest must fall, which it can’t do, if it is already at 2 percent]. Thus the proceeds realised from the increased output will disappoint the entrepreneurs and employment will fall back again to its previous figure, unless the marginal propensity to consume is equal to unity [i.e., there is no additional saving] or the reduction in money-wages has had the effect of increasing the schedule of marginal efficiencies of capital relatively to the rate of interest and hence the amount of investment [Keynes means, of course, increase the amount of investment that is profitable — i.e., yields 2 percent or more]. For if entrepreneurs offer employment on a scale which, if they could sell their output at the expected price, would provide the public with incomes out of which they would save more than the amount of current investment, entrepreneurs are bound to make a loss equal to the difference; and this will be the case absolutely irrespective of the level of money wages. [26]

I have italicized the last sentence because if any single sentence of Keynes can express the theoretical substance of his doctrine, that is the one. [27]

[27] Another passage from Keynes that provides conclusive support for my exposition of his views is this one, which appears earlier in The General Theory: “. . . the position of equilibrium, under conditions of laissez-faire, will be one in which employment is low enough and the standard of living sufficiently miserable to bring savings to zero. . . . Assuming correct foresight, the equilibrium stock of capital . . . will, of course, be a smaller stock than would correspond to full employment of the available labour; for it will be the equipment which corresponds to that proportion of unemployment which ensures zero saving. Ibid., pp. 217–218.

The Grounds for the MEC Doctrine

It is now necessary to present the reasons Keynes and his followers advance in support of the declining mec doctrine — of the claim that as net investment increases, the rate of return on capital must fall. Keynes himself writes:

If there is an increased investment in any given type of capital during any period of time, the marginal efficiency of that type of capital will diminish as the investment in it is increased, partly because the prospective yield will fall as the supply of that type of capital is increased, and partly because, as a rule, pressure on the facilities for producing that type of capital will cause its supply price to increase . . . . Thus for each type of capital we can build up a schedule, showing by how much investment in it will have to increase within the period, in order that its marginal efficiency should fall to any given figure. We can then aggregate these schedules for all the different types of capital, so as to provide a schedule relating the rate of aggregate investment to the corresponding marginal efficiency of capital in general which that rate of investment will establish. We shall call this the investment demand-schedule; or, alternatively, the schedule of the marginal efficiency of capital. [28]

[...] To express these ideas in terms of a simple example, we might imagine that initially the price of a machine that turns out widgets is $1,000 and that its use enables the same quantity of labor to produce 10 additional widgets every year, which have a selling price of $10 each. On the simplifying assumptions that this machine will last forever and that the cost of materials and fuel can be ignored, the implied rate of return is 10 percent per year: 10 additional widgets times $10, divided by $1,000. Now, however, there is a demand for two such machines. As a result, the purchase price rises above $1,000 — say, to $1,050. In addition, the selling price of widgets will fall somewhat, because of their larger supply — say, to $9.50. Finally, because of diminishing returns, it may be possible to obtain only 9 additional widgets instead of 10 by virtue of the employment of the second machine. The operation of any one of these factors, it is held, reduces the rate of return. Their combined operation in this example must reduce the rate of return to not much more than 8 percent: $9.50 times 9 widgets, divided by $1,050. In these ways, more net investment is held to reduce the rate of return on capital. [30]

3. Critique of the IS-LM Analysis The Declining-Marginal-Efficiency-of-Capital Doctrine and the Fallacy of Context Dropping

The use of the declining-marginal-efficiency-of-capital doctrine enables the Keynesians to end up claiming that a fall in wage rates and prices cannot achieve full employment, precisely by dropping the context of a fall in wage rates and prices and rise in employment, and switching to an altogether different, indeed, opposite context, which could exist only if wages rates, production costs, and prices rose instead of fell. For the context to which the Keynesians deftly switch is one of a rise in the prices of capital assets, no fall in the costs of production but constant or, indeed, rising costs of production, and no increase in the quantity of labor employed relative to the supply of capital goods in existence, but, on the contrary, a further increase in the supply of capital goods relative to the supply of labor that is employed.

Recall that the first reason advanced in support of the falling marginal efficiency of capital was the claim that as more net investment took place to offset the additional saving accompanying the additional employment, the prices of capital assets would rise, in response to the increase in demand for capital assets allegedly constituted by the additional net investment. [...]

The fact is that the additional net investment presupposes and is in response to lower prices of capital assets, and can endure only so long as the prices of the capital assets are lower. It does not operate to raise those prices. And this is true even if one were to grant the legitimacy of conceiving of the additional net investment as representing an additional total expenditure of money for the capital assets. It would still be necessary to keep in mind that the larger expenditure of money was in response to lower prices and could endure only so long as the prices of capital assets remained lower. [34]

[34] In reality, of course, it is an error to conceive of net investment as an actual expenditure. As we know, rather than being an expenditure, net investment is in fact the difference between productive expenditure, which is the actual expenditure present, and business costs, which are largely an accounting abstraction, based on the productive expenditures of previous accounting periods. On this point, see above, pp. 702–705.

Recall that the second reason advanced for the declining marginal efficiency of capital was the claim that more net investment means more capacity in place, which means lower selling prices of products, which, other things being equal, means a fall in profitability. … Again, the Keynesians contradict the context. They argue that a fall in wages, costs, and prices cannot achieve full employment because if all that occurred were the fall in selling prices and no fall in costs — indeed, a rise in costs because of the alleged rise in the prices of capital assets — the rate of return on capital would fall. … This dropping and switching of context enables the Keynesians to fail to see that the lower selling prices of products are offset and in fact more than offset by a fall in costs of production, and thus that there is not only no fall in the rate of profit (the “marginal efficiency of capital”), but an actual rise in the rate of profit in consequence of the fall in wages and costs of production.

Finally, it should be recalled that the third reason advanced in support of the declining marginal efficiency of capital was the claim that diminishing returns would accompany the additional net investment that was required to offset the additional saving taking place as employment, output, and real income expanded. Now putting aside the actual irrelevance of the law of diminishing returns to the rate of profit, and assuming for thesake of argument that it did have a determining effect,the truth is that in the context of a fall in wage rates and prices and increase in the volume of employment and output, the physical returns to capital goods would increase rather than decrease. This is because as the economic system moves from mass unemployment to full employment, the supply of labor employed in production increases at a more rapid rate than the supply of capital goods. This is so because in the conditions of mass unemployment a substantial supply of capital goods previously used in production continues to exist in the form of idle machines and factories. Its existence relative to the diminished number of workers employed constitutes an unusually high ratio of capital to labor. As the workers come back into the factories and once again take up the use of these capital goods, the ratio of capital to labor sharply declines.

[...] Indeed, the whole process by which the Keynesians reach the conclusion that a fall in wage rates and prices cannot achieve full employment is nothing more than a refusal to consider its actual existence. Instead of considering the existence of a fall in wage rates, costs, and prices and the employment of a larger number of workers, they choose to consider the totally different and opposite case of a rise in the prices of capital assets, of no fall in the costs of production but only in the selling prices of products, and of no increase in the supply of labor employed but only of an increase in the supply of capital goods that derives from that employment.

The Marginal-Efficiency-of-Capital Doctrine and the Claim That the Rate of Profit Is Lower in the Recovery from a Depression Than in the Depression

There are further major criticisms which must be made of the Keynesian analysis in connection with the marginal-efficiency-of-capital doctrine. The Keynesian claim that a fall in wage rates and prices cannot achieve full employment, because at full employment the rate of return on capital would be too low, is a claim that the rate of return in the recovery from a depression is lower than it is in the depression.

What the Keynesians claim is that the economic system cannot recover from mass unemployment and depression because if somehow it did, the rate of return on capital would fall — which means that it would be lower in the recovery from the depression than it was in the depression. In effect, the Keynesians tell us that if we think the rate of profit is low now, in the conditions of mass unemployment and depression, we should wait and see what it will look like in the recovery. In the state of mass unemployment and depression, it is already at the minimum acceptable level (in the neighborhood of 2 percent) and at full employment it would have to be lower still, they say. Indeed, according to the Keynesians, if somehow the economic system did temporarily manage to recover and achieve full employment, it would immediately have to return to the conditions of mass unemployment and depression as the means of elevating the rate of profit — above the still lower level that is supposed to exist in the recovery. This is the actual meaning of the whole Keynesian argument for the unemployment equilibrium. If there is any doubt about this fact, the reader should look once again at the standard Keynesian diagrammatic relationships presented above in Figure 18–4 of this chapter and reread the extensive passage quoted from Keynes himself some paragraphs later, in which he claims to “rebut the crude conclusion that a reduction in money wages rates will increase employment.”

The Unemployment-Equilibrium Doctrine and the Claim That Saving and Net Investment Are at Their Maximum Possible Limits at the Very Time They Are Actually Negative

An equally profound and closely related reversal of economic reality on the part of the Keynesian analysis is its belief that in a depression [net] saving and net investment are at their maximum possible limits, and the problem is that full employment requires that they be carried still further. [36] This, of course, is the alleged proximate cause of the marginal efficiency of capital having to be pushed below its minimum acceptable level. The actual fact is, however, that far from being at their maximum limits, saving and net investment are extremely low or even negative in a depression. For example, in the Great Depression following 1929, corporate saving (undistributed corporate profits) was negative in every year from 1930 to 1936 and again in 1938; personal saving was negative in 1932 and 1933 and barely more than zero in 1934; net investment was negative in the years 1931 to 1935 and again in 1938. [37] [Note : under continued substantial inflation, saving and investment are unlikely to be negative]

There should be nothing surprising in these facts. They are logically implied in the very nature of a depression and mass unemployment. When people are out of work, they must live off their savings. In a state of mass unemployment, the consumption of savings in this way is necessarily very considerable. At the same time, corporations are under pressure to continue to pay dividends to their stockholders, even though they are currently earning little or no profits. To pay dividends under such conditions, they must dip into their accumulated savings — their earned surplus accounts. Unincorporated businesses, of course, are under the same kind of pressure; they too must frequently continue to support their owners even though their current profits are insufficient to do so. In these ways, the current saving of those individuals and business firms who are still in a position to save out of income is more than offset, and saving in the economy as a whole becomes nonexistent or, indeed, becomes negative.