I have highlighted in bold what I consider to be the most important passages.

Capitalism: A Treatise on Economics

by George Reisman, 1996.

CONTENT

CHAPTER 12 MONEY AND SPENDING

CHAPTER 13 PRODUCTIONISM, SAY’S LAW, AND UNEMPLOYMENT

PART B SAY’S (JAMES MILL’S) LAW

5. Falling Prices Caused by Increased Production Are Not Deflation

CHAPTER 16 THE NET-CONSUMPTION/NET-INVESTMENT THEORY OF PROFIT AND INTEREST

Capital Intensiveness and the Monetary Component in the Rate of Profit

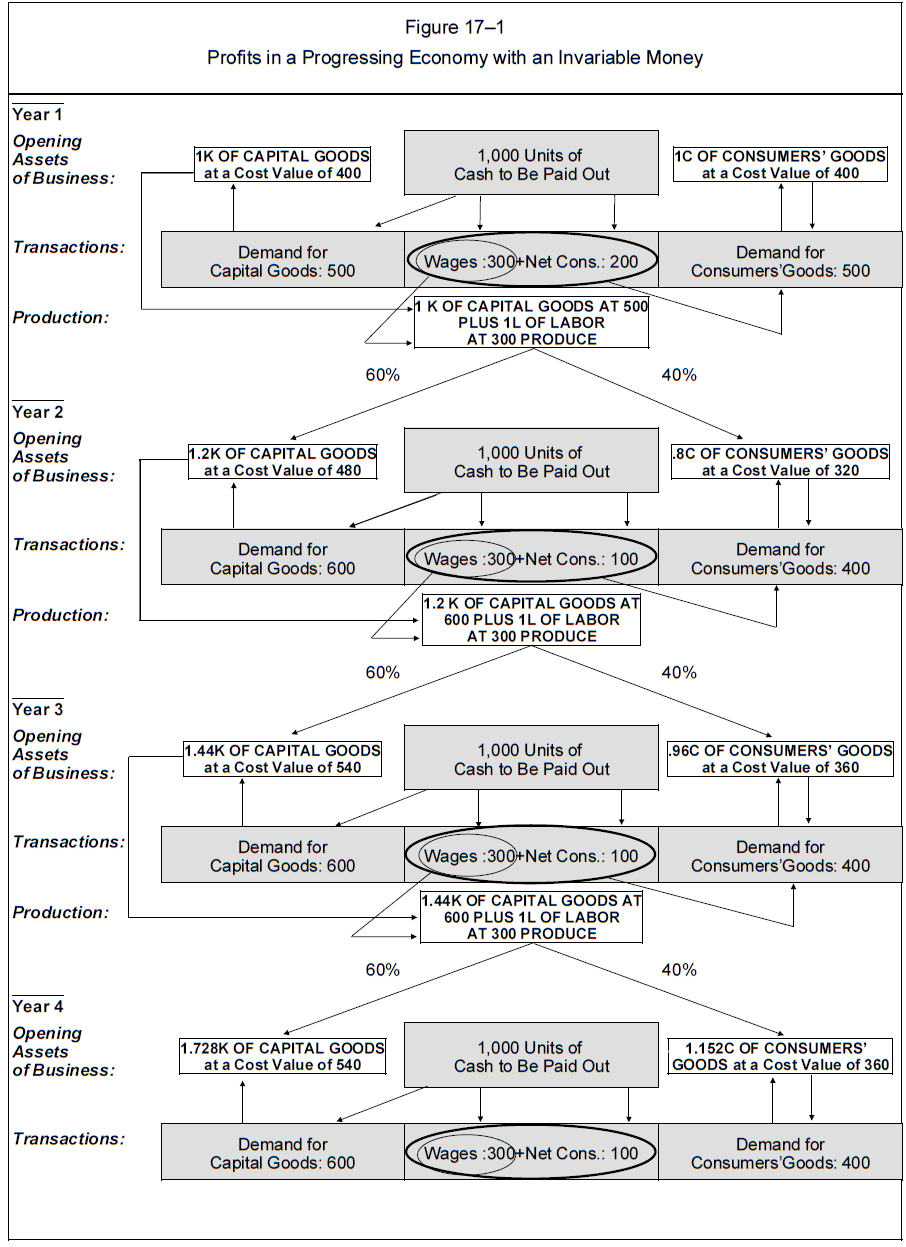

CHAPTER 17 APPLICATIONS OF THE INVARIABLE-MONEY/NET-CONSUMPTION ANALYSIS

Confirmation of Fact That Falling Prices Caused by Increased Production Do Not Constitute Deflation

CHAPTER 12 MONEY AND SPENDING

3. The Quantity of Money and the Demand for Money

[…] The demand for money is determined by a variety of factors. One of the most important, and, indeed, the most fundamental, is the security, or lack of security, of property. Where property is insecure — where it is subject to arbitrary confiscation by the government or to plunder by private gangs — saving and provision for the future will be low, because people will not be in a position to count on benefitting from it. But such saving and provision for the future as does occur will largely take the form of holding precious metals and gems — items easily concealable and easily transportable. A gold money in such circumstances has a very low velocity of circulation. 23

23. For the sake of brevity, in what follows I generally refer to gold and gold money, but, of course, my discussion applies equally to silver and silver money.

By the same token, under conditions in which property is secure from confiscation and plunder, the demand for gold for holding will be less, and thus the velocity of circulation of a gold money will be greater. The same result is aided by the development of financial markets and financial institutions, which make it easier and more profitable for people to invest their savings rather than hold them in the form of precious metals or precious stones.

Interestingly, the effect of lack of security of property is very different on a paper money than on a gold money. In conditions in which a government loses the power to stop private plunder or itself becomes a looter, people switch their savings from assets denominated in the government’s paper to precious metals and precious stones. They lose the desire to hold such paper, because it becomes more and more likely that the government will sharply reduce its value by rapidly increasing its supply. Thus, the velocity of a paper money tends to rise in such circumstances.

The velocity of money can also be increased by such developments as improvements in transportation, which reduce the time money is in transit and correspondingly increase the speed with which it is available for respending. The development of clearing houses reduces the amount of money that is required to perform a given volume of transactions: instead of all of the transactions needing to be effected by means of the transfer of money, only the settlement of the net amounts owed or owing, after the canceling of offsetting debts by the clearing process, needs to be effected by means of the actual transfer of money. The money set free by the clearing process is thereby made available for spending for other things. Thus, the total spending that the same quantity of money can effect is increased.

What is especially worthy of note is the fact that in the context of an economic system with developed financial institutions and financial markets, saving operates to raise the velocity of circulation of money. (This may be the cause of some surprise, in view of the popular fallacy that confuses saving with hoarding.) There are two reasons for this. First, under such conditions funds that are saved are likely to be made available for spending sooner than funds that are held for consumption. For example, the part of his paycheck that an individual deposits in his savings account is available for lending by the bank almost immediately. However, the part of his paycheck that he retains in his possession in the form of cash that he plans to spend on consumers’ goods in the coming days or weeks prior to his receipt of his next paycheck will enter into the hands of others only over the length of this considerably longer period. Second, to the extent that the availability of additional savings contributes to credit being readily available, it becomes possible for individuals and business firms to substitute to some extent the prospect of obtaining such credit for the holding of money as the means of providing for their future need for funds. To this extent, they reduce their cash holdings and thus bring about a rise in the velocity of circulation of money. 24

It should be realized that in the conditions in which the velocity of circulation of a gold money rises, there is unlikely to be any fall in the purchasing power of gold as a result. This is the case because the rise in velocity here is the accompaniment of a process that sharply increases the physical ability to produce — above all, the growth of saving and the channelling of those savings into productive investment. In addition, a further factor that must be mentioned, which is especially relevant in appraising the effects of the development of clearing procedures, is that the productive process also tends to become more complex at the same time that the demand for gold holdings falls. Because of the intensification of the division of labor, which is inextricably bound up both with the growth of saving and investment and the increase in production, a tendency exists toward an increase in the number of payments needed in the production and distribution of ultimate consumers’ goods. For example, instead of a farmer selling his food to a consumer, he sells it to a food processor, who sells to a wholesaler, who in turn sells to a retailer. Possibly several processors and wholesalers are involved. The intensification of such specialization and its requirement for additional acts of exchange more or less keeps pace with the decline in the desire to own balances of gold. Consequently, while the total of spending of all types combined rises relative to the quantity of gold, it does not follow that spending specifically for consumers’ goods rises relative to the quantity of gold. In other words, the velocity that actually rises is the so-called transactions velocity, but not necessarily income velocity, or certainly not to the same degree. (Furthermore, it should not be assumed that either the fall in demand for gold holdings or the growth in complexity of the productive process necessarily goes on indefinitely.)

CHAPTER 13 PRODUCTIONISM, SAY’S LAW, AND UNEMPLOYMENT

PART B SAY’S (JAMES MILL’S) LAW

5. Falling Prices Caused by Increased Production Are Not Deflation

[...] The fact that the falling prices resulting from increasing production are not accompanied by a decline in the general or average rate of profit represents an enormous departure from the conditions of a genuine deflation. In a genuine deflation, business profits are almost universally depressed, if not eliminated altogether. But we have seen that the aggregate profit of the economic system can be represented by the difference between the spending of consumers to buy products and the wages paid by business to produce them, and that so long as those magnitudes, and thus the difference between them, remain the same, the aggregate profitability of business is totally unaffected by the physical volume of goods and services produced and sold. Thus, when production increases, prices fall. That is perfectly true. But the general rate of profit does not.

By the same token, when prices fall because of an increase in production, there is nothing present that would cause any general increase in the difficulty of repaying debts, which is the most prominent symptom of a genuine deflation. A fall in prices resulting from more production in the face of constant sales revenues does not mean that there is any greater difficulty of earning any given sum of money. If, over a period of years, an increase in production, let us say a doubling, is achieved by virtue of business firms becoming more efficient, then the conditions of the case imply that the mathematically average business firm produces twice the output just as easily as it previously produced its original output. True enough, a unit of output sells for only half the price. But, by the conditions of the case, the average business firm has twice the units to sell. Its sales revenues in money are, therefore, just as great as they were before, and no more difficult to earn. Whatever money it is obliged to repay, does not come to it with greater difficulty than was originally the case.

It is certainly true that individual firms and whole industries could find it more difficult to repay their debts as prices fell. These would be the firms that did not improve their efficiency while their competitors did, and the industries that were relatively overexpanded. These firms and industries would suffer a decline in sales revenues and profits, and probably incur outright losses. But for every firm and industry in this position, there are other firms and industries that enjoy correspondingly increased sales revenues and profits and a correspondingly enhanced ability to repay their debts. Namely, the firms that introduce improvements ahead of their competitors, and the industries that are relatively underexpanded. There is no overall pressure on debtors here — nothing present that operates against debtors as a class.

Thus, it is simply incorrect to think of falling prices per se as “deflation.” The falling prices caused by more production share only one symptom of deflation — namely, the fall in prices itself. They do not share two further, essential symptoms of deflation — namely, the sudden reduction or total elimination of business profitability and the increased difficulty of repaying debts.

What accounts for the combination of these three symptoms of deflation together is not any increase in production or supply, but a decline in monetary demand — a contraction of spending — which occurs as the result of a drop in the quantity of money or at least a slowing down of its rate of increase. A drop in total spending reduces prices. That is one of its effects. In addition, and totally unlike an increase in production and supply, it also reduces total business sales revenues. This reduces the availability of funds with which to repay debts. It makes it more difficult for the average seller to earn any given sum of money, because there is simply less money to go around. In addition, and again totally unlike an increase in production and supply, a drop in total spending reduces the general rate of profit, because while sales revenues fall immediately as a consequence of a decline in spending in the economic system, total costs of production in the economic system fall only with a time lag. For example, depreciation cost continues to reflect the larger volume of spending on account of plant and equipment that existed in the past. [...]

The Anticipation of Falling Prices

[...] The first thing that must be pointed out is that even if the prospect of falling prices caused by increases in production did increase the demand for money, which it does not, the increase would be of an essentially one-time nature. Once the increase in the demand for money took place, further increases in production and the falling prices they caused would take place with no further increase in the demand for money.

For example, let us suppose that there is a given, fixed quantity of money in the economic system and that initially the aggregate demand for consumers’ goods is 500 monetary units and the aggregate demand for labor is 400 monetary units ... We can assume that initially production and prices are both constant from year to year. And now we assume that production begins to rise and prices to fall from year to year and, for the sake of argument, in response to the fall in prices and the prospect of the fall continuing, the demand for money rises. If it occurred, the rise in the demand for money would have the effect of reducing the monetary demand for consumers’ goods and labor. For the sake of illustration, let us assume that the effect would be to reduce the demand for consumers’ goods and labor by 10 percent, namely, from 500 and 400 respectively to 450 and 360 respectively. From this point on, it is clear, production would increase and prices would fall with no further increase in the demand for money and no further fall in the monetary demands for consumers’ goods and labor.

[...] The only reasonable basis for a further rise in the demand for money based on the anticipation of falling prices caused by increases in production would be if the rate of increase in production and fall in prices accelerated. In that case, it might plausibly be argued that there would be a one-time further increase in the demand for money and a one-time further fall in the aggregate demands for consumers’ goods and labor.

Thus, even if the argument alleging deflationary effects were correct, which it is not, it would still be essentially false. For at most, it would apply only to a transition phase. Thereafter, once the additional demand for money was satisfied and the volume of spending in the economic system stabilized at a lower level, production could go on increasing and prices go on falling at any given rate with no further increase in the demand for money, exactly as I have described.

[…] Insofar as the increasing production and falling prices are the result of improvements in the productivity of labor, the falling prices do not lead to a postponement of consumption and thus do not increase saving at the expense of consumption. This is because they are the accompaniment of the average person having a higher real income and thus being better off in the future than in the present, which prospect gives him as much motivation to consume more as the prospective increase in the buying power of money gives him to postpone consumption and save more. 52 Inasmuch as the two incentives are thus mutually offsetting, there is no overall tendency for consumption spending to fall, or saving to increase, as the result of falling prices caused by increases in production — not insofar as the increases in production and fall in prices are the result of a higher productivity of labor.

When increases in saving do occur, the demand for money does not increase, but, if anything, decreases. This is because … the average rate of profit and interest in the economic system is always both positive and sufficiently high — in the absence of monetary contraction — to make it worthwhile to invest savings that are available for any significant period of time rather than hoard them. In such an environment, as we saw in the last chapter, the effect of an increase in saving is actually to reduce the demand for money, both because funds that are saved are normally available for spending sooner than funds that are held for consumption and because savings are the source of credit, the prospective availability of which reduces the need to hold money. 53 […]

Economic Progress and the Prospective Advantage of Future Investments Over Present Investments

[...] Thus, to the extent that there is economic progress, the machines of the future will be more efficient than those of the present and therefore today’s machines will be at a competitive disadvantage in comparison with them. The question that arises is whether this circumstance might operate to depress current investment by creating the prospect of losses or, at any rate, lower profits than could be obtained by delaying investment, and whether it might thus operate to cause an increase in the demand for money as well as to inflict losses on the producers of plant and equipment, who would have to cut their prices in the present in order to be competitive with the plant and equipment of the future.

The answer is that if economic progress took place only once, or were just about to take place for the first time, then it would be true simply that the machines of the present would be at a competitive disadvantage with the machines of the future, with the result that a rise in the demand for money might ensue and the new machines of the present might have to be sold at a loss if their competitive disadvantage were major. Observe, however, that the increase in the demand for money would exist only until the expected more advanced machines arrived on the market, and the loss would be borne only by the machines which did not embody the progress. The arrival of the more advanced machines would put an end to any increase in the demand for money. They would be in demand and would not sell at a loss. More importantly, it should be realized that if improvements in machinery are a repeated occurrence and are expected, there is no increase in the demand for money and no problem of the owners or producers of machinery incurring losses because of the prospective introduction of more efficient machines in the future.

This is because in such conditions, while the machines of next year may be expected to be more efficient and at a competitive advantage over the machines of this year, the machines of this year are, for their part, more efficient and at a competitive advantage over the machines of last year and previous years. Because of their greater efficiency and higher productivity, the machines of this year account for a disproportionately large share of total production, when compared to the machines of last year and previous years.

[...] Similar observations apply to the case of inventory and the fear that business would always have to sell its inventories at a loss, because of continuously falling costs and prices. The fact is that to the same extent that older inventories must be sold at a loss, newer inventories can be sold at a correspondingly enhanced profit. This proposition can be demonstrated for the case of any given rate of increase in production and any given ratio of inventories to sales. If, for example, production were to double from period to period, and half of current production were always to remain in and constitute inventory, then in any given period sales would represent half of the production of the current period plus half of the production of the previous period, which was half as great. Thus, two-thirds of current revenues would be attributable to half of the production of the current period and one-third of current revenues would be attributable to half of the production of the previous period. To the same extent that the half of the production of the previous period brought in deficient revenues, the half of the production of the present period that is currently sold would bring in additional revenues. Thus, the general rate of profit would not be affected. What is present here is nothing fundamentally different from the fact that businesses are profitable despite the fact that they run clearance sales on which, considered in isolation, they incur a loss; the losses on the clearance sales are compensated for by the profits on regular operations.

I have said that if economic progress took place only once, or were just about to take place for the first time, then it would be true simply that the machines of the present would be at a competitive disadvantage with the machines of the future, with the result that a rise in the demand for money might ensue and the new machines of the present might have to be sold at a loss. This is actually an overstatement of matters, because unless such a situation were pervasive, that is, applied to the greater part of the economic system at the same time, the decline in expenditure to buy the machines even of a fairly substantial number of industries would almost certainly not represent a decline in expenditure in the economy as a whole. The funds not expended for the machines in question would be made available for other purposes and be expended elsewhere. The only way that spending in the economic system as a whole would be reduced is if economic progress throughout the economic system, or at least in the greater part of the economic system, were about to take place for the first time or, what would be very similar, were about to undergo some significant acceleration. Only in such unusual cases, would spending in the economic system as a whole temporarily fall, awaiting the appearance of the improved machines. [...]

CHAPTER 16 THE NET-CONSUMPTION/NET-INVESTMENT THEORY OF PROFIT AND INTEREST

Net Investment Versus Negative Net Consumption

Because of net investment, it would be possible for an aggregate profit to exist in the economic system even in the complete absence of net consumption — indeed, even in the face of negative net consumption.

Net consumption falls below the consumption of businessmen and capitalists to the degree that wage payments fail to be accompanied by equivalent consumption expenditures. At the crudest level of analysis, one might imagine a portion of wage payments simply being hoarded by the wage earners. To this extent, receipts from the sale of consumers’ goods to wage earners would be less than wage payments, and the excess of total receipts from the sale of consumers’ goods over wage payments would be correspondingly diminished. The excess of total sales revenues over total productive expenditure would, of course, also be equivalently reduced, inasmuch as it reflects merely the addition of the demand for capital goods both to the demand for consumers’ goods and to the demand for labor. The addition of equals to both sides of a diminished inequality does not alter the diminution of the inequality.

More realistically than being hoarded, a portion of wage payments might be used to finance additional productive expenditures. One can imagine, for example, employee stock-purchase plans, under which a portion of wages is turned back to business firms and used by the firms for the purchase of additional capital goods (or even for the payment of wages to additional workers). The same results would follow to the extent that the savings of wage earners that were deposited in banks were used in making loans to business firms, which then expended the proceeds of the loans in these ways. If — for lack of a better description — such secondary productive expenditures should exceed the financing of wage earners’ consumption by means of loans extended by business firms, then, to that extent, consumption on the part of wage earners as a group would be less than the payment of wages.

The implication of a fall in net consumption here can also be seen in the fact that each dollar of wage income paid by business that is used to make productive expenditures represents two dollars of productive expenditure for every one dollar of sales revenues. This is because there is first a dollar of productive expenditure in the payment of the wages, and then, to the extent that the wages themselves are used to finance productive expenditure, a second dollar of productive expenditure in the expenditure of the wages. There is only one dollar of sales revenue, however, which occurs when the wages are expended in the purchase of capital goods, or when the wage earners whose wages are paid by means of secondary productive expenditure, purchase consumers’ goods.

In these cases, total sales revenues in the economic system would still be the same, but productive expenditure would be larger and net consumption, therefore, as the difference between sales revenues and productive expenditure, would be equivalently reduced. Looked at in more detail, to the extent that the wage earners’ savings were used to buy capital goods, receipts from the sale of capital goods would replace receipts from the sale of consumers goods to wage earners. This fall in receipts from the sale of consumers’ goods, in the face of the same wage payments, would represent diminished net consumption. To the extent that the wage earners’ savings were used to employ additional producers’ labor, whose wages, it may be assumed, were themselves fully consumed, the result would be that while receipts from the sale of consumers’ goods stayed the same, the total wages paid by business would rise. Either way, net consumption would be reduced.

It could also be the case, of course, that the savings of wage earners that were turned back to business would make possible merely the continuation of the same amount of productive expenditure in the next period instead of a larger amount of productive expenditure in the current period. In this case, the situation would resemble the case of hoarding on the part of the wage earners, in that sales revenues in the current period would be reduced by the amount of such saving, and thus the difference between sales revenues and productive expenditure — i.e., net consumption — would again be equivalently reduced. Unlike the case of hoarding, however, business would receive back the cash it had expended, though in the form of loans or receipts from the sale of securities rather than in the form of sales revenues.

If businessmen and capitalists themselves consumed little or nothing, say, 5 or 10 monetary units instead of 100 or 200 monetary units, and at the same time there were a significant excess of secondary productive expenditure over the granting of new and additional consumer loans by business to wage earners — that is, if the net amount of secondary productive expenditure were significant — the excess of wage payments over the consumption of wage earners would mean the existence of negative net consumption. But even in such an unlikely case, a significant aggregate profit and average rate of profit could still exist in the economic system on the strength of net investment alone. This is illustrated in Tables 16–8 and 16–9.

Table 16–8 assumes that the consumption of businessmen and capitalists is zero and thus that productive expenditure is the only source of sales revenues. It further assumes that a portion of wage payments is simply hoarded. It shows that despite this, an aggregate profit can exist on the basis of net investment. Specifically, the table assumes that the demand for capital goods is 500, and that while the demand for labor is 300, the wage earners consume only 200, because they have chosen to hoard 100 of their wages. Thus, sales revenues in the economic system turn out to be only 700 (500 + 200), while productive expenditure is 800 (500 + 300). The underlying basis of this shortfall of sales revenues in comparison with productive expenditure, namely, that wage earners consume only 200, while their wages are 300, represents negative net consumption in the amount of 100 — viz., 200 of consumption minus 300 of wages. Nevertheless, even with sales revenues less than productive expenditure, an aggregate profit exists in Table 16–8 by virtue of the costs deducted from sales revenues being further below productive expenditure than are sales revenues. With aggregate costs of 600, as the table assumes, there is an aggregate profit of 100 on the 700 of sales revenues. At the same time, the subtraction of these aggregate costs from 800 of productive expenditure results in net investment of 200. Thus 200 of net investment offsets 100 of negative net consumption and results in an aggregate profit of 100.

The excess of productive expenditure over sales revenues described in Table 16–8 could continue virtually indefinitely if, instead of the current saving of the wage earners being hoarded, which is a case so unlikely that it actually deserves hardly any consideration, they were used in financing loans to business or in purchasing securities from business. In this way, business could repeat its current level of productive expenditure in the next period.

Table 16–9 arrives at an essentially similar result to that of Table 16–8 under the assumption that a portion of wages is used to finance secondary productive expenditure in the same accounting period. It shows the wage earners’ saving of 100 of their incomes resulting in a secondary productive expenditure of 100, which is added to the original, primary productive expenditure of 800, thereby bringing total productive expenditure to 900. For the sake of simplicity, the secondary productive expenditure is assumed to be entirely in the form of an additional demand for capital goods. Thus, Table 16–9 shows a demand for capital goods of 500 + 100 and identical receipts from the sale of capital goods of 500 + 100. By the same token, while it shows 300 of demand for labor, it shows only 200 of receipts from the sale of consumers’ goods to wage earners. Thus, while productive expenditure is 900 (500 + 100 + 300), sales revenues are only 800 (500 + 100 + 200). The reason for the disparity, it must be recalled, is that the use of wages to buy capital goods adds to productive expenditure, but does not add to sales revenues; the expenditure for the capital goods merely takes the place of expenditure for consumers’ goods. Because wages themselves are part of productive expenditure, the use of wages to make further productive expenditures has the ability in an extreme case such as the present, to raise productive expenditure above sales revenues.

Thus, in this case, there is again a shortfall of sales revenues relative to productive expenditure in the amount of 100, which represents negative net consumption in the amount of 100 (viz., only 200 of consumption accompanying 300 of wages). But once again, an aggregate profit exists on the strength of net investment — viz., on the strength of costs being below productive expenditure to an extent sufficient to enable them to be below the sales revenues that are below productive expenditure. In Table 16–9, net investment in the amount of 300 is accompanied by profit in the amount of 200. The net investment reflects the fact that while productive expenditure is 900, costs are only 600. Profit is 200, because even though sales revenues are 100 less than productive expenditure, costs are 300 less, which means that costs are 200 less than sales revenues. Thus, in this case, 300 of net investment offsets 100 of negative net consumption and results in an aggregate profit of 200. 51

51. Net investment and profits are 100 larger in Table 16–9 than in Table 16–8 — i.e., 300 and 200 respectively versus 200 and 100 respectively — because the 100 of wage-earner saving is spent for capital goods rather than being hoarded or turned back to business in the form of loans or securities purchases to finance productive expenditure in the following period. In being spent in this way, it adds 100 both to productive expenditure and to sales revenues. In enlarging both productive expenditure and sales revenues by 100 in the face of the same aggregate costs of 600, it adds 100 to both net investment and profits.

It must be stressed that the possibility of negative net consumption is extremely remote to begin with, since most savings of wage earners are used to finance consumption expenditures, such as the purchase of homes or personal automobiles, and to the extent that they are not, are largely or entirely offset by loans to wage earners from business for such purposes. Thus, as a practical matter, as I have already said, it is reasonable to assume that virtually 100 percent of wages has a counterpart in consumption expenditure. Moreover, to the extent that savings are used to finance loans for consumption expenditures, the payment of interest on such loans represents a source of return on savings over and above ordinary net consumption — a source that may be termed secondary net consumption.

This is the case because the use of wages to pay interest on consumer loans not only constitutes consumption expenditure from the perspective of those who pay the interest, and, at the same time, interest income from the perspective of those who receive the interest, but also does not diminish the demand for the products of business. This last is because the recipients of the interest are able to spend the proceeds in buying goods or services from business. Thus the demand for the products of business remains the same, while the total of consumption expenditure and the total of interest income in the economic system are increased.

For example, total wage payments in the economic system could be 300 monetary units, of which the wage earners consume 270 monetary units in buying consumers’ goods from business and pay 30 monetary units in interest on consumers’ loans. The recipients of the 30 in consumers’ interest — who could well be wage earners themselves, insofar as they had saved, and their savings had been lent to consumers — could then expend that 30 in buying consumers’ goods of their own from business. As a result, everything would be the same except that 30 more in consumers’ interest had been paid. The situation would be analogous to the case of the wage earners using part of their wages to employ consumers’ labor — or paying taxes to the government, which uses the proceeds to employ consumers’ labor.

In those cases, the effect is to increase the overall demand for labor while leaving all other spending magnitudes the same. 52 Here, the interest on consumer loans is not at the expense of the profits and interest earned on the capital invested in ordinary business firms, but stands as a further source of net consumption and thus of aggregate profit and interest in the economic system. In fact, insofar as it is equivalent to net income, the payment of such interest constitutes a direct addition to the amount of net consumption in the economic system. This is because it is both consumption and, not being wages, an addition to the amount of consumption in excess of wage payments. 53 (Of course, the rate of interest on consumer loans, like the rate of interest on loans to business firms, is governed by the rate of profit on capital invested in business. This is because investing in business or lending to business is typically an alternative for whoever lends to consumers. At the same time, if additional funds are required for loans to consumers, the sources will most likely be parties presently engaged in these activities.)

However, what is decisive is that even if negative net consumption were to exist, however unlikely that might be, its existence would necessarily be strictly temporary and would be followed by the resumption of a significantly positive rate of net consumption. As the analysis of the next subsection will show, this is because net investment can be indefinitely prolonged. As net investment occurs, the amount of capital invested in the economic system increases. So too, of course, does the volume of accumulated savings, which is comprised both of capital, which is by far its main constituent in any modern economic system, and savings invested in the financing of loans to consumers. In the context of an economic system with an invariable money [i.e., money of invariable value, see pp. 536-540], in which the sales revenues of business have a fixed limit and all other spending magnitudes are also constrained by the fixity of the quantity of money, the increase in accumulated capital and savings is not only an absolute increase, but also an increase relative to consumption expenditure and incomes. In other words, it constitutes an increase in the degree both of capital intensiveness in the economic system and in provision for the future relative to provision for the present. As a result, its effect is to provide the basis for greater and greater consumption expenditure relative to income, which puts an end to all possibility of negative net consumption. 54

The Process of Capital Intensification

A related approach for understanding the process whereby net investment ultimately must disappear under an invariable money [see pp. 536-540], is to observe just how the economic system becomes more capital intensive as the result of a process of saving. At the same time, this will provide further understanding of the fact that any possible negative net consumption that might temporarily exist as the result of saving on the part of wage earners, must also disappear.

This approach requires tracing out the process of capital intensification step by step. This is done in Table 16–10. In this table, the economic system is assumed to begin with an annual aggregate expenditure for consumers’ goods of 500 units of money. The total value of the capital employed in this economic system at all stages of production combined is assumed initially to be 1,000 units of money. This sum is the value of all the land, buildings, fixtures, plant, and equipment of business firms, less accumulated depreciation reserves, plus the value of all the inventories and work in progress that business firms possess. It also includes the quantity of money held by business firms. 66 Please note that what is referred to here is the value of the capital stock of the economic system, not the annual expenditure for capital goods.

The ratio of accumulated capital to consumption, or, more precisely, to the sum of consumption plus net investment, is typically called the capital-output ratio. More correctly, of course, it should be called the capital-net-output ratio, inasmuch as consumption plus net investment represents the net product of the economic system, not the actual total output. 67 Because of the equality between net product and national income, the ratio can also be expressed as the ratio of capital to national income. 68 Its closeness to the ratio of capital to consumption makes it obvious that the so-called capital-output ratio can be taken as a measure of the degree of capital intensiveness in the economic system, alongside the ratios we have mainly used up to now, namely, the ratio of capital to consumption, wages, and sales revenues respectively. 69

What is necessary at this point is to trace out how saving brings about a rise in the capital-net-output ratio from its initial level to a higher level. For the sake of simplicity, the example describes how the ratio is raised from an initial level of 1,000⁄500 to 1,500⁄500, or from 2:1 to 3:1. It should go without saying, that the principles contained in this example are applicable to the process of capital intensification in general, that is, to a rise in the capital-net-output ratio from any given starting level to any other given level, and for any absolute values of consumption expenditure (or consumption expenditure plus net investment) and the capital stock.

The table assumes that the process of capital intensification is brought about by a reduction in consumption expenditure from 500 to 450 for a period of 10 years. It assumes that in each of these 10 years 50 of savings out of net income are invested and added to the preexisting value of the accumulated capital stock, which means that 50 of net investment occurs in each year. It further assumes that once the value of the capital stock has been increased by a cumulative total of 500, so that the ratio of accumulated capital (savings) to income stands at 3:1, people are content with their degree of provision for the future and thus restore their consumption expenditure to 500.

The first column of the table is simply a series of years. The second column, K, presents the amount of accumulated capital year by year; the third, C, the amount of consumer spending year by year; and the fourth, I, the amount of net investment year by year. For the sake of simplicity, I follow my usual practice of assuming that all financial transactions take place on the first day of the year. ... Thus, for example, the accumulated capital of 1,050 shown for Year 3 both incorporates the 50 of net investment made in Year 3 and serves in the production of the net output that becomes available at the start of Year 4.

For each year, the fifth column of the table, K/(C+I), presents the ratio of accumulated capital to the so-called net national product (NNP), which, of course, is equal to the sum of consumption plus net investment and to national income. Initially, NNP is equal to 500 of consumption expenditure alone, and will be once again, at the conclusion of the process. But in the interval, as the process of capital intensification takes place, NNP is equal to the sum of 450 of consumption plus 50 of net investment. Because the net product of the economic system comes to be divided into these two portions, 450 of consumption and 50 of net investment, the total accumulated capital stock of the economic system comes to be divided into two corresponding portions: the one portion serving in producing the part of the net product purchased by the consumers, the other portion serving in producing the part of the net product that constitutes net investment.

The division of the capital stock in this way is shown in the last two columns of the table, headed K1/C1 and K2/I1. It should be observed that C1 is the demand for consumers’ goods of the following year, and, accordingly, K1 is the portion of existing accumulated capital employed in the production of consumers’ goods to be sold in the following year. By the same token, I1 is the volume of net investment of the following year, and K2 is the portion of existing accumulated capital employed in the production of the portion of next year’s NNP that is represented by net investment. (This aspect of the table is similar to Figures 16–1 and 16–2, in which the disposition of the factors of production within each year is assumed to conform to the pattern of the relative demands for consumers’ goods and capital goods in the following year. The difference is that now the disposition of the net output in the following year between consumption and net investment is taken in place of the relative demands for consumers’ goods and capital goods, which categories of goods, of course, are the components of gross output. 70)

In Table 16–10, Year 1 represents an initial equilibrium. It shows how the economic system has been operating up to this point. The value of the capital stock is 1,000, the demand for consumers’ goods is 500, and the capital-net-output ratio is 2:1. 71 In Year 2, consumption spending continues to be 500 and saving and net investment continue to be zero. But in this year, the allocation of capital undergoes an important change, in anticipation of the drop in consumption of 50 and emergence of 50 of net investment that is to occur in Year 3, and which will be maintained for a total of 10 years, viz., through Year 12. Accordingly, in Year 2, 100 of capital is transferred from the production of consumers’ goods for Year 3 to the production of the part of the net output of Year 3 that will be represented by net investment. Hence, in Year 2, K1/C1 is 900⁄450 and K2/I1 is 100⁄50. To describe matters in terms of concretes, what will happen in Year 3 is that there will be 50 less of spending for such goods as residential housing and personal automobiles, and 50 more of spending for such goods as factory buildings, trucks, and freighters. Accordingly, in Year 2, 100 of capital is shifted from the production of such goods as residential housing and personal automobiles to the production of such goods as factory buildings, trucks, and freighters.

In Year 3, 50 of saving and net investment occur and result in a rise in the accumulated capital of the economic system from 1,000 to 1,050. This additional 50 of capital is divided between the production of consumers’ goods for Year 4 and the production of the portion of the net output of Year 4 which is represented by net investment; that is, it is divided in the ratio of Year 4’s demand for consumers’ goods to Year 4’s net investment, i.e., in the ratio of 450:50, or 9:1. Thus, 45 of the additional capital is devoted to the production of consumers’ goods of Year 4, and 5 of the additional capital is devoted to the production of the part of the net output of Year 4 that is represented by net investment. Observe that from this point on the employment of capital in the production of consumers’ goods begins rising. Both the production of consumers’ goods and the production of the goods represented by net investment become progressively more capital intensive.

The process of increasing capital intensiveness in the production both of consumers’ goods and the portion of net output represented by net investment continues from Year 3 to Year 11. By Year 11, total capital has risen from 1,000 to 1,450, of which 1,305 are employed in the production of consumers’ goods for Year 12, and 145 in the production of the part of the net output of Year 12 that will constitute net investment. In Year 12, however, the final 50 of additional capital is accumulated, and, at the same time, the allocation of capital is shifted back from the industries producing for net investment and the increase in capital intensiveness to the industries producing consumers’ goods. This is because having achieved the desired higher ratio of accumulated savings to current income by Year 12, people once again consume the whole of their nominal incomes starting in Year 13.

Of course, both the beginning and the end of the process need not be as abrupt as I have described it. There could be a gradual increase in saving and net investment accompanied by a gradual shift in the allocation of capital to the production of goods representing net investment. And the later, reverse movement could be equally gradual. Nor is it necessary that the changes in the consumption/saving pattern be anticipated with the precision I have presented. Any lack of anticipation of the initial shift will result in comparatively higher profits for the capital goods industries and comparatively lower profits for the consumers’ goods industries, because to this extent there will be a greater demand relative to supply in the case of capital goods and a smaller demand relative to supply in the case of consumers’ goods. By the same token, lack of anticipation of the later, reverse shift will result in comparatively higher profits for the consumers’ goods industries and comparatively lower profits for the capital goods industries, because now the opposite imbalance would ensue.

Under all conditions, however, at the end of the process, the net effect is that people end up with greater provision for the future (both absolutely and relatively), production is more capital intensive, the supply of goods is more abundant and can go on increasing more rapidly (thanks to the increased ability to implement technological advances that more capital intensiveness makes possible), and people restore their consumption expenditure in a condition in which they are better able to afford to do so. It thus works out to be the same as for an individual, who first saves and, as a result, later on puts himself in the position of being able to afford to step up his consumption.

And in just this way, any saving on the part of wage earners which did have the effect of bringing about negative net consumption would prove temporary. It would go on only until wage earners had accumulated savings sufficient to enable them to consume the whole of their wages, at which point, everyone in the economic system would be better off than he had been before. (To be sure, the wage earners would not only consume the whole of their wages but the whole of any profits or interest currently earned on the capital they had accumulated.)

It should be realized, although it is not stated explicitly, that the accumulation of capital and savings in the present analysis leads to a reduction in productive expenditure along with the restoration of consumption expenditure, just as in the previous analysis. This fact is present implicitly in the restoration of consumption expenditure and disappearance of net investment.

7. The Inherent Springs to Profitability

This chapter has shown how the productive process generates its own profitability through net consumption and net investment. It has shown how net investment in the context of an economy with an invariable money, in raising the degree of capital intensiveness, lays the foundation for capital accumulation and rising production and thereby an increasing quantity of commodity money. It has shown how this last, in raising the level of spending from year to year, both perpetuates net investment and adds a corresponding positive component to the rate of profit.

What must be realized now is that these sources of profit are virtual springs to profitability, which operate to restore profitability whenever it might temporarily be lacking for any reason (notably, because of a financial contraction and ensuing depression). Insofar as net consumption exists — and it must exist, whenever savings have been accumulated in a sufficient ratio to income and consumption — the only thing which can prevent the existence of an aggregate profit is negative net investment, which certainly cannot be more than a temporary phenomenon. An increasing quantity of money and rising volume of spending, the by-product of capital accumulation and increasing production, also cannot fail to reestablish profitability.

The potential for net investment, which always exists, constitutes an even more powerful spring to profitability, one whose power increases as the prevailing rate of profit decreases. Whenever aggregate profitability is lacking, not only is net investment sufficient to restore it, but, in addition, as I will show, net investment is more and more encouraged by the fact that the lower is the rate of return on capital, the higher is the degree of capital intensiveness that pays, and thus the more powerful is the stimulus to the existence of net investment, as the means of achieving a higher degree of capital intensiveness. Thus, the economic system is so constituted that if the rate of profit should ever become unduly low, or disappear, that very fact encourages a move toward further capital intensiveness and thereby the calling into being of net investment, which restores the rate of profit. Once I have demonstrated these propositions concerning net investment, it will be possible not only better to understand what causes and perpetuates depressions and unemployment, but also to appreciate just how alien such phenomena are to the actual nature of a capitalist economy.

In order to understand the principle of potential additional net investment serving as a spring to profitability, the context of discussion must be carefully defined. The context is the general rate of profit in the economic system as a whole. More than that, it is the general rate of profit in the economic system as a whole as determined apart from changes in the quantity of money and the overall volume of spending. In other words, it is the rate of profit insofar as it is determined by the rate of net consumption and by the rate of net investment apart from changes on the side of money.

The naming of the first proviso, that it is the general rate of profit in the economy as a whole that is under consideration, should make it possible to avoid committing the fallacy of composition and making an invalid generalization from the consequences of a low rate of profit in an individual industry to the consequences of a low rate of profit in the economic system as a whole. In the case of an individual industry, a low rate of profit means a low rate of profit relative to rates of profit in other industries. The effect of this, of course, is to discourage investment in that industry, indeed, to encourage the withdrawal of capital previously invested. But the context under discussion here is ... that of a low rate of profit prevailing throughout the economic system. If this is kept in mind, then it will not be difficult to see how in these conditions, a low rate of profit actually works to encourage more capital investment rather than less.

[...] Let us consider, first, the case of a railroad company which is contemplating whether it should construct its line straight through a mountain by digging a tunnel, or detour around the mountain. Digging the tunnel, we assume, constitutes the more-capital-intensive method in that it requires a greater initial capital investment than the alternative. But once in existence, the tunnel would make possible, virtually forever, an annual saving in operating costs, because it would reduce the time required for trains to reach their destination. In reaching its decision, what the railway company considers is how much money the tunnel would potentially save it every year on the basis of savings of train-crew time, fuel consumption, and wear and tear of rolling stock, versus how much more it must invest to construct the tunnel in comparison with the less-capital-intensive detour around the mountain.

The railroad company will decide in favor of the tunnel if the annual savings the tunnel achieves are, when divided by the extra capital its construction requires, greater than the going rate of profit on capital. It will decide against the tunnel if the savings the tunnel achieves are, when divided by the extra capital its construction requires, less than the going rate of profit on capital. For example, imagine that the existence of the tunnel would make possible an annual saving in operating costs of $1 million per year in comparison with the alternative route, and that at the same time, the construction of the tunnel requires $10 million more of capital investment than the alternative route. In this case, the railroad company will decide in favor of the tunnel if the going rate of return on capital is less than 10 percent. It will decide against the tunnel if the going rate of return on capital is more than 10 percent. This is because its investment in the tunnel will yield a rate of return of 10 percent ($1 million per year divided by $10 million). Whether or not this investment should be undertaken depends on a comparison of its profitability with the profitability of other investments. If the profitability of other investments is greater than 10 percent, then the capital that might be devoted to this investment should instead be devoted to them. If, on the other hand, the profitability of other investments is less than 10 percent, then this investment represents the better alternative, and it should be undertaken.

The essential point here is that the lower is the general rate of return on capital, the better does this particular investment appear by comparison. With a general rate of return of greater than 10 percent, this particular investment is submarginal — that is, it is insufficiently profitable to be undertaken. With a general rate of return of 10 percent, it becomes borderline. With a general rate of return of less than 10 percent, it becomes relatively attractive, and more and more so, the further below 10 percent the general rate of return falls. And as the general rate of return falls below 10 percent, still other investments become attractive by comparison. Capital-intensive improvements representing annual savings in cost equal to only 9 percent, 8 percent, 7 percent, and so on, successively become relatively attractive as the general rate of return falls below these levels. And not only in railroading, of course, but in every area of the economic system. In effect, the general rate of return operates as a standard, a test, which each particular capital-intensive improvement must pass in terms of the size of the annual cost reductions it achieves relative to the additional capital it requires. As the general rate of return falls, the standard — the passing grade, as it were — is reduced, with the result that a growing number of capital-intensive investments become relatively profitable, and the degree of capital intensiveness that pays is increased throughout the economic system. Furthermore, what applies to cost reductions applies equally to quality improvements. The additional revenues derived from these, relative to the additional capital that needs to be invested to achieve them, becomes less and less, as the general rate of return falls.

It pays to examine the same principle at work in another example. Thus, imagine a product that can be produced in a given quantity by any of three different methods of production, representing three different degrees of capital intensiveness. (The differences in capital intensiveness can be taken as reflecting different combinations of production by hand or by machine. The most-capital-intensive method uses the most machinery. The least-capital-intensive method uses the least.) We call these three methods, simply, A, B, and C. As shown in Table 16–16, method A is the least capital intensive, but also the most costly. It requires an investment of $10,000 of capital and results in $9,000 of annual costs to produce a given quantity of the product. Method B requires $20,000 of capital to produce the same quantity of the product but enables production to take place at an annual cost of only $8,000. Finally, method C requires $30,000 of capital to produce the same quantity of the product but enables production to take place at the still lower annual cost of only $7,000.

In the conditions of this example, as the revenue derived from the sale of a given quantity of the product declines, and thus, in the face of given costs, reduces profitability, the effect is to favor methods of production of greater capital intensiveness. The stimulus given to methods of greater capital intensiveness is shown in Table 16–16 by the effects on profits and the rate of profit of three different magnitudes of sales revenues. The largest magnitude of sales revenues, $11,000, which appears in the upper portion of the table, in the row labeled “Annual Sales Revenues (1),” is accompanied by profits of $2,000, $3,000, and $4,000 for methods A, B, and C respectively, and thus by corresponding rates of profit of 20 percent, 15 percent, and 131⁄3 percent respectively. These results appear lower in the table, in the respective rows “Annual Profits (1)” and “Annual Rate of Profit (1).” With sales revenues at $11,000, method A, the least-capital-intensive method, is the relatively most profitable.

When sales revenues for the same quantity of product fall to $10,000, the profits of methods A, B, and C, with their respective costs of $9,000, $8,000, and $7,000, fall to $1,000, $2,000, and $3,000, respectively. This results in the three methods of production now earning the same rate of profit on capital, given their respective capital requirements. These results are shown in the rows labeled “Annual Profits (2)” and “Annual Rate of Profit (2).”

When, finally, sales revenues fall to $9,000, as shown in the row labeled “Annual Sales Revenues (3),” the profits of method A are totally eliminated. Method B continues to show a profit of $1,000, which yields a rate of profit of 5 percent on the $20,000 of capital which must be invested in that method. But method C continues to show a profit of $2,000, which represents a rate of profit of 62⁄3 percent on the $30,000 of capital which must be invested in it. By comparison method C, the most capital intensive of the three methods, is now favored. These results appear in the rows labeled “Annual Profits (3)” and “Annual Rate of Profit (3).”

This outcome should in no way be thought paradoxical. What brings it about is the fact that the more-capital-intensive methods are the lower-cost methods. As sales revenues for a given quantity of the product fall, the only way to remain profitable is by achieving lower costs of production. The way to achieve that is by investing more capital. 94

As I have indicated, a lower rate of profit favors more capital intensiveness not only in cases in which more capital intensiveness achieves lower-cost methods of production, but also in cases in which more capital intensiveness achieves a better quality of products. An example which clearly brings out this principle is the case of thirty-year-old scotch versus eight-year-old scotch. Thirty-year-old scotch is a much higher-quality scotch than eight-year-old scotch. Its production also requires the use of substantially more capital per unit of output and is thus correspondingly more capital intensive. If thirty-year-old scotch is to be produced on a regular basis, then for every unit of scotch reaching the market in any particular year, there must be twenty-nine other units, age one through twenty-nine, in the hands of its producers. If eight-year-old scotch is to reach the market on a regular basis, there need be only seven other units — the units age one through seven — in the hands of its producers, for every unit that comes to the market in any given year.

The rate of profit on capital invested is one of the determinants of the prices of goods. And its role is the more pronounced, the more time consuming and capital intensive the production of a product is, and also the higher is the rate of profit. If the rate of profit is 10 percent per year, then for every $100 invested in a quantity of raw scotch, the price of eight-year-old scotch must provide $214, for that is the sum required to yield a 10 percent annual rate of profit on $100 compounded for eight years. By the same token, for every $100 invested in a quantity of raw scotch, the price of thirty-year-old scotch must provide the vastly larger sum of $1,745, because that is the sum required to yield a 10 percent annual rate of profit on $100 compounded for thirty years.

Observe. In this case, with the rate of profit at 10 percent, the thirty-year-old scotch must sell for more than eight times the price of the eight-year-old scotch, so greatly does the 10 percent rate of profit influence its relative price. But now let us see what happens if the rate of profit were 5 percent instead of 10 percent. To yield a rate of profit of 5 percent compounded for eight years, the eight-year-old scotch would have to sell for $148. To yield a 5 percent rate of profit compounded for thirty years, the thirty-year-old scotch would have to sell for $432. In this case, with the rate of profit at 5 percent, the thirty-year-old scotch need sell for only 2.9 times the price of the eight-year-old scotch, instead of more than 8 times the price of the eight-year-old scotch ... The lower is the rate of profit, the smaller is the premium which must exist in the price of the older scotch. If the rate of profit were zero, the price of thirty or even one-hundred-year-old scotch would need to be no higher than the price of the eight-year-old scotch.

Now what is significant from the point of view of the present discussion, about the prices of the two scotches moving closer together as the rate of profit falls, is that this development is bound to favor the demand for the older, better-quality scotch. As the premium on this scotch falls, people will be able to give greater and greater consideration to its superior quality. As a result, the share of the market served by this more-capital-intensive product increases, and thus the need is created for the overall degree of capital intensiveness in this industry to go up. [...]

The principle here sheds further light on the effects of a fall in the rate of profit on the use of more-capital-intensive methods of production in general. For example, with a rate of profit of 10 percent per year, a machine which costs $1,000 and lasts 10 years, must, if it is to be worthwhile, bring in each year the sum of $150 in the sales revenue of the product it helps to produce. This sum reflects an annual depreciation charge of $100 plus a 10 percent rate of return on the average capital outstanding in the machine over its life, which latter is one half of the initial capital invested, viz., $500. Thus, over its ten-year life, the machine must bring in a revenue over its cost of $500 — i.e., 10 times ($150-$100). But if the rate of profit were 5 percent instead of 10 percent, then the machine would need to bring in each year only $125, and thus, over its ten-year life, only $250 in revenue over its cost. With the reduction in the premium in the revenue from the sale of the product that is required to make a machine pay, the value of the machinery employed in production necessarily tends to increase. And, of course, identically the same principle applies to the value of the buildings employed in production. Thus, the wider principle that capital intensiveness is favored as the rate of profit falls receives further confirmation.

In a very similar way, it can be shown that as the rate of profit falls, the growth of the more-capital-intensive industries in the economic system is favored relatively to the growth of the less-capital-intensive industries ... This is shown in Table 16–17. There, Industry A, with a ratio of sales to capital of 10:1, is the least capital intensive. Industry B, with a ratio of sales to capital of 1:1, is more capital intensive. Industry C, with a ratio of sales to capital of only 1:3, is the most capital intensive. (We can think of Industry A as representing supermarkets, which have an extremely rapid turnover of the portion of their capitals that is invested in inventories, and thus a very high overall ratio of sales to capital. Industry B can be taken as representing the automobile industry. And Industry C, finally, can be taken as representing the electric utility industry, almost all of whose capital is invested in power plants and wires underground, both with an extremely long life.)

The fact that these industries have such unequal rates of capital turnover (the sales to capital ratios) requires, of course, that they have correspondingly unequal profit margins — that is, profits as a percentage of sales — if they are all to earn the same rate of profit on capital invested. 95 Thus, in order for Industry A to earn a 10 percent rate of profit on capital invested, it requires a profit margin of only 1 percent. If it earns a profit of a mere 1 percent of sales, but its sales are 10 times its capital, it earns a 10 percent rate of profit on its capital. Industry B needs to earn a profit margin of 10 percent, if, with its 1:1 ratio of sales to capital, it is to earn a 10 percent rate of profit on its capital invested. And, of course, Industry C needs to earn profits on sales of fully 30 percent, if, with its 1:3 ratio of sales to capital, it is to earn a 10 percent rate of profit on its capital invested. All this is shown in the top half of Table 16–17.

The bottom half of Table 16–17 shows the profit margins that are required in the three industries if the rate of profit on capital invested is 5 percent instead of 10 percent. These lower profit margins are ½ percent, 5 percent, and 15 percent, respectively.

Now inasmuch as these lower profit margins are brought about by a fall in the selling prices of the products of the three industries, Table 16–17 implies that a decline in the rate of profit causes a relatively greater reduction in the prices of the products of more-capital-intensive industries than of less-capital-intensive industries. As the rate of profit falls from 10 percent to 5 percent, the price of the product of industry C falls by 15 percent, that of B by 5 percent, that of A by only ½ percent, for these are the extent of the price declines needed to achieve the respective reductions in profit margins. Because of this pattern of price reductions, the demand for the products of more-capital-intensive industries is favored, and therefore the need for capital intensiveness in the economic system is once more increased.

Thus, to summarize, a lower rate of profit on capital invested encourages greater capital intensiveness in the economic system by reducing the cost savings that more-capital-intensive investments must achieve relative to the additional capital required. This was shown in the example of the railroad tunnel. It is also accompanied by a more rapid wiping out of the profit margins of higher-cost, less-capital-intensive methods of production than of the profit margins of lower-cost, more-capital-intensive methods of production, with the result that the more-capital-intensive methods are rendered the comparatively more profitable. This was shown in the example of the three methods of producing the same quantity of the same product. In addition, a lower rate of profit reduces the premiums in price or in revenue that more-capital-intensive products, more capital-intensive-methods of production, and more-capital-intensive industries must bear relative to less-capital-intensive products, methods of production, and industries. This was shown in the example of scotch of different ages, the example of the additional revenue required to make the use of machinery or buildings pay, and, finally, the example of the industries of different degrees of capital intensiveness. In all these ways, a lower rate of profit favors a higher degree of capital intensiveness.

If this principle is understood, then it should now be possible to understand the claim made earlier that if for any reason the rate of profit is wiped out or made unduly low, the basis exists for an automatic restoration of profitability through net investment. All one has to realize is that when confronted with an unduly low rate of profit, businessmen are motivated to divert outlays for factors of production from some of their present lines to lines representing a higher degree of capital intensiveness, because, by comparison, these will appear as more profitable lines. Thus, if most businesses are earning little or no profit with the employment of their present amounts of capital, then what they need is more capital, in order to reduce their annual costs of production and/or to increase their sales revenues by virtue of having improved products to sell. In this situation what will happen is a withdrawal of capital from some of its present lines of employment and diversion to more-capital-intensive lines, as representing a more profitable use of existing capital. For example, unprofitable retail businesses will withdraw some of their capital from the retailing trade and make it available in the loan market, where it will be borrowed and used for the construction of things like additional railway tunnels. At the same time, some of the retailers will merge with one another, in order to carry on business more capital intensively and more economically. Such retailers will themselves probably seek additional capital.

What is present here is a shifting of productive expenditures from points less remote from showing up as costs of production to points more remote from showing up as costs of production, with the result that for a more-or-less-extended period of time a reduction takes place in the costs business subtracts both from its outlays for factors of production and from its sales revenues. 96 This reduction in costs deducted is the reflection of a larger proportion of the output of the economic system being retained within business firms, instead of being turned over to customers in the sale of inventories or lost through depreciation or expensed expenditures. On the one side, it represents the accumulation of assets, which is a hallmark of net investment and the growth in capital intensiveness. On the other side, it represents an increase in profitability. Thus, the effect of the impetus toward additional capital intensiveness is a restoration of business profitability on the strength of the additional net investment entailed.

Of course, as my discussion of the sources of profit has shown, the restoration of profitability achieved by additional net investment is not confined to the existence of that net investment itself. The net investment spring presently under discussion tends to activate the other springs to profitability as well. This is because the higher degree of capital intensiveness that is brought about operates to increase production and thus, in the long run, and indirectly, the rate of increase in the supply of a commodity money. 97 The net investment spring also activates the net consumption spring in that the elimination of negative net investment immediately allows net consumption to generate profits equal to itself. 98 Moreover, in the conditions of recovery from a depression, the accompaniment of the net investment spring is a reduction in the demand for money for holding, which, in the short run, further adds to net investment and the nominal rate of profit, by raising productive expenditure and sales revenues relative to costs.

Wage Rate Rigidities and Blockage of the Springs

Given the existence of the various springs to profitability that have now been explained, the question arises of why the economic system does not in fact always spring back to profitability in the midst of a depression. One part of the answer, of course, is that the process of financial contraction and deflation must first come to an end, so that the financial losses inherent in that process can be avoided. Another essential part of the answer, which is necessary to limit the extent of the financial contraction and deflation, is that there must be a sufficient fall in wage rates. Before the critical net-investment spring can be activated, wage rates must fall to the level required for full employment in the face of the existing demand for money and quantity of money — a demand for money that is greater than it was before the depression, and a quantity of money that is very possibly smaller than it was before the onset of the depression. The demand for money in a depression is greater both because it has been deprived of the stimulus to spending created by inflation and credit expansion, and because of the existence of the process of financial contraction itself, especially when accompanied by bank failures under a fractional reserve banking system, which serve to reduce the quantity of money.

As I explained in Chapter 13, the failure of wage rates to fall to the full-employment point causes a postponement of investment expenditures, and thus a wiping out of net investment and profitability, indeed, causes negative net investment and losses. 99 The operation of the springs to profitability comes into play only when wage rates reach the new, lower level that has become necessary for full employment, thereby eliminating the threat that present investments will be rendered unprofitable by substantial wage-rate reductions in the year or two ahead. At that point, the operation of the springs guarantees the restoration of net investment and profitability.

Capital Intensiveness and the Monetary Component in the Rate of Profit

[...] A question now arises concerning specifically the monetary component that is added to the rate of profit by virtue of the more rapid increase in the supply of commodity money that a higher degree of capital intensiveness brings about. Namely, does the monetary component in the rate of profit operate to reverse the increase in the degree of capital intensiveness that brought it about in the first place, as would a rise in the rate of net consumption or a rise in the rate of net investment brought about by carrying on the process of capital intensification too rapidly?

There is some important evidence for believing that the rise in the rate of profit caused by the monetary component does not have this effect, that it does not react back, as it were, and undermine the higher capital intensiveness on which it rests. This is because there is reason for believing that the relationship between capital intensiveness and the rate of profit pertains exclusively to that portion of the rate of profit that does not reflect the increase in the quantity of money.

The case of the thirty-year-old scotch versus the eight-year-old scotch can be used to perform an intellectual experiment that will demonstrate this point. We have seen how a fall in the rate of profit from 10 percent to 5 percent encouraged capital intensiveness by causing the price of the older scotch to fall to a greater extent than that of the younger scotch and thus to encourage the purchase of the older, more-capital-intensive scotch at the expense of the purchase of the younger, less-capital-intensive scotch. Now what we will do is see if this encouragement to greater capital intensiveness is reversed by virtue of a more rapid rate of increase in the quantity of money that restores the rate of profit to 10 percent.

We saw that the fall in the rate of profit from 10 percent to 5 percent caused the price of the thirty-year-old scotch to fall from $1,745 to $432, while it caused the price of the eight-year-old scotch to fall from $214 to $148. This implied a fall in the ratio of the price of the older to the younger scotch from over 8:1 ($1,745⁄$214) to less than 3:1 ($432⁄$148). The test of whether or not an addition to the rate of profit by virtue of an increase in the quantity of money undermines the higher capital intensiveness on which the increase in the quantity of money rests will be whether or not the change in the relative prices of the two scotches is reversed by the more rapid rate of increase in the quantity of money.

For the sake of simplicity, we can assume that a more rapid rate of increase in the quantity of money takes place that is sufficient fully to restore the rate of profit, namely, to raise it all the way back up to 10 percent from the 5 percent to which it fell on the basis of a reduction in the rate of net consumption. If in raising the rate of profit back up to 10 percent, the increase in the quantity of money raises the ratio of the price of the thirty-year-old scotch to the price of the eight-year-old scotch back to 8:1, then we will have to conclude that the rise in the rate of profit caused by the more rapid increase in the quantity of money that is attributable to greater capital intensiveness does, indeed, work against the capital intensiveness on which it rests. If, on the other hand, we find that the rise in the rate of profit attributable to the more rapid growth in the quantity of money is not accompanied by any rise in the ratio of the price of the thirty-year-old scotch to the price of the eight-year-old scotch, then we must conclude that this kind of rise in the rate of profit does not work against capital intensiveness.

Well, what do we find? We find that if the quantity of money and volume of spending in the economic system now begin to increase at an annual rate of 5 percent (which is what will operate to raise the rate of profit from 5 percent to approximately 10 percent), the price of thirty-year-old scotch tends to be elevated by a factor of 1.0530, which is an increase of 4.32 times. 100 Thus, instead of being $432, it will tend to be $432 x 4.32, or $1,867. By the same token, the price of eight-year-old scotch will tend, in eight years, to be elevated from $148 to $148 x 1.058, or to $218. On this basis, it may appear that the old 8:1 ratio is restored.