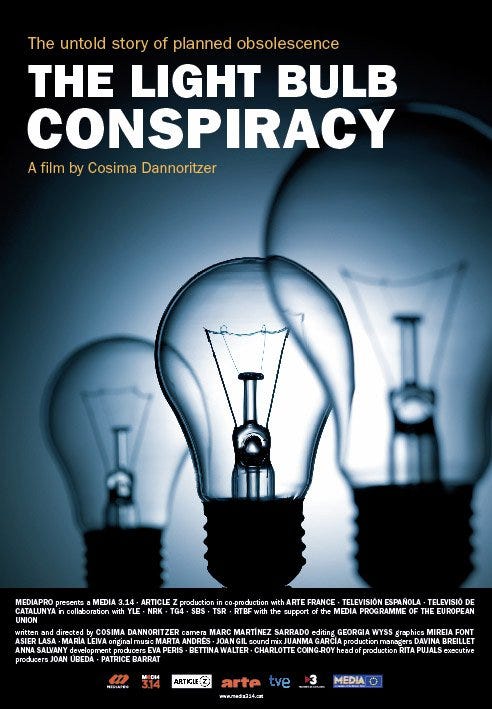

“The Light Bulb Conspiracy” is a 2010 documentary realized by Cosima Dannoritzer aiming to denounce the planned obsolescence which consists in degrading the life expectancy of consumer goods with the final goal to ‘induce’ people to buy more and more of their products, leading to a perpetual overconsumption. An outcome allowed by cartels and monopolies.

CONTENT

Cognitive biases

The true story of the bulb obsolescence

Theoretical fallacies of planned obsolescence & monopoly price

Cognitive biases

The tendency to idealize the past, believing that life was better before, believing the goods had longer-life expectancy, is a good illustration of survivorship bias. Perceptual and cognitive biases lead us to believe that the products were more durable before, because we remember the very old refrigerators in working condition today, due to standing before our very own eyes, while we have forgotten the hundreds of machines that have ended up in the landfill. That is best known as survivorship bias. But anecdote is not data.

In an affluent society where we were raised like spoiled children, we do not even realize all these things that work, because it seems so usual. When something breaks, it feels like the world is collapsing around us. The frustration is felt more strongly when we are reminded that advertisements are everywhere and that big companies make so much money. The idea that this defect was due to an external cause is even more tempting. Faced with disappointment, the consumer convinces themselves that their purchase wasn’t a result of their own choice but rather the seductive advertisements, which, as if by some mysterious influence, compelled them to buy products they neither like nor ever will.

In fact, such opinions are totally inappropriate. In an article published in Slate, Engber reports a study showing that people’s perception of temperature depends more on political views than on temperature deviations.

Is Air Conditioning Bad for You? The biology and ideology of home cooling. By Daniel Engber/Posted Thursday, Aug. 2, 2012, at 3:45 AM ET

So much so, in fact, that the people surveyed all but ignored their actual experience. No matter what the weather records showed for a given neighborhood (despite the global trend, it had gotten colder in some places and warmer in others), conservatives and liberals fell into the same two camps. The former said that temperatures were decreasing or had stayed the same, and the latter claimed they were going up. “Actual temperature deviations proved to be a relatively weak predictor of perceptions,” wrote the authors. [...]

People’s opinions, then, seem to have an effect on how they feel the air around them. If you believe in climate change and think the world is getting warmer, you’ll be more inclined to sense that warmth on a walk around the block. And if you tend to think instead in terms of crooked scientists and climate conspiracies, then the local weather will seem a little cooler.

This is exactly what Dan Gardner explained in his 2008 book “Risk: The Science and Politics of Fear” (page 135) :

The power of confirmation bias should not be underestimated. During the U.S. presidential election of 2004, a team of researchers led by Drew Westen at Emory University brought together 30 committed partisans - half Democrats, half Republicans - and had them lie in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) machines. While their brains were being scanned, they were shown a series of three statements by or about George W. Bush. The second statement contradicted the first, making Bush look bad. Participants were asked whether the statements were inconsistent and were then asked to rate how inconsistent they were. A third statement then followed that provided an excuse for the apparent contradiction between the statements. Participants were asked if perhaps the statements were not as inconsistent as they first appeared. And finally, they were again asked to rate how inconsistent the first two statements were. The experiment was repeated with John Kerry as the focus and a third time with a neutral subject.

The superficial results were hardly surprising. When Bush supporters were confronted with Bush’s contradictory statements, they rated them to be less contradictory than Kerry supporters. And when the explanation was provided, Bush supporters considered it to be much more satisfactory than did Kerry supporters. When the focus was on John Kerry, the results reversed. There was no difference between Republicans and Democrats when the neutral subject was tested.

All this was predictable. Far more startling, however, was what showed up on the MRI. When people processed information that ran against their strongly held views - information that made their favoured candidate look bad - they actually used different parts of the brain than they did when they processed neutral or positive information. It seems confirmation bias really is hard-wired in each of us, and that has enormous consequences for how opinions survive and spread.

It is quite possible that individuals having anti-market bias simply exaggerate trivial events. Insofar as inequality increases, the growing sense of injustice could push more individuals to adopt anti-market positions. Interestingly, Napier and Jost (2008) reported that conservatives are happier than liberals, and that the growth of inequality affects the level of happiness more among liberals than among conservatives, because liberals do not accept inequality as easily as the conservatives. But overall, income inequality seems to reduce happiness as reported by individuals (see also, Kahneman et al., 2006). The fact that the rich are getting richer at a faster rate than the poor is obviously not an idea that is accepted among most people. But when a device ceases to function without any apparent, comprehensible reason, resentment against capitalism is even more stimulated. Hence the temptation to blame the big firms increases along with the feeling that the products become less and less sustainable.

The true story of the bulb obsolescence

But if some products are less durable today than they were before, it should be kept in mind that goods are not homogeneous. Some products benefit from being durable, and others from being less. It could be argued that a bulb lasting 50 years may have its advantages, as we avoid the trouble of changing the bulb and take the risk of falling from a ladder. In contrast, a car lasting 50 years will soon become obsolete over time. That a product benefiting from being durable has seen its life expectancy falling does not prove that obsolescence was planned, especially because of the difficulty in distinguishing between the obsolescence that is “planned” or “adapted” to the ever-changing consumers’ preferences. The explanation is that a producer has to make a compromise. Greater efficiency can be implemented at the expense of life expectancy, and vice versa. If a bulb gains to be sustainable, it also gains to be effective. If durability has been reduced, it is because the luminous efficiency has become a more important criterion for the consumer’s point of view.

Some historical points have been reported in the documentary. We are told that a cartel between producers of bulbs during the 1920s planned to reduce the life expectancy of the bulbs for the sole purpose of encouraging consumers to excessive purchases.

But the facts tell us another story. Here’s a passage from the 1951 Report on the Supply of Electric Lamps :

125. The main factors in the design of a filament lamp are its life on the one hand and its luminous efficiency, i.e. the amount of light per unit of power (watt), on the other. A lamp designed to give high luminous efficiency has a shorter life than one designed to give a lower luminous efficiency and a long life ; in other words, an increase in the life of a lamp can only be obtained at the expense of efficiency. The cost of production of the lamp would be much the same whatever the life. For ordinary lighting, therefore, the relative importance of luminous efficiency and of long life (from the consumer’s point of view) depends on the relative costs of replacing lamps and of power. Where power is relatively expensive it is more economical to use high efficiency lamps and vice versa. In practice a single standard only of life has been adopted both here and in many other countries. The current B.S.I, specification for ordinary lamps, No. 161, lays down a minimum life of 1,000 hours and minimum values of luminous efficiency. The life of 1,000 hours is adopted as a standard in many countries though the United States adopts a lower figure for some ratings; it has been used in the United Kingdom since 1921, during which period the luminous efficiency has been substantially increased. Any figure chosen must be a compromise as the cost of power to different classes of consumer varies considerably and there is, therefore, no single optimum.* Some commercial users, however, have told us that they obtain longer life by “under-running” lamps (i.e. using lamps designed for, say, a 240 volt system on a 230 volt supply), particularly in positions where the cost of replacing lamps is considerable. (Chapter 9: Quality and Standards)

It has often been alleged — though not in evidence to us — that the Phoebus organisation artificially made the life of a lamp short with the object of increasing the number of lamps sold. As we have explained in Chapter 9, there can be no absolutely right life for the many varying circumstances to be found among the consumers in any given country, so that any standard life must always represent a compromise between conflicting factors. B.S.I, has always adopted a single life standard for general service filament lamps, and the representatives of both B.S.I, and B.E.A., as well as most lamp manufacturers, have told us in evidence that they regard 1,000 hours as the best compromise possible at the present time, nor has any evidence been offered to us to the contrary. (Chapter 17: Conclusions and Recommendations)

Theoretical fallacies of planned obsolescence & monopoly price

Now, a cartel has no reason to thrive in a free market economy. This is due to the possibility of opportunistic behavior which remains a constant threat to the stability of any cartel. The more intense the competition, and the more difficult it is to coordinate strategies. The only way to maintain the cartel is to impose barriers to entry in order to limit competition. For example, Reisman (1996, pp. 377-380) explains how the government creates and maintains monopolies.

Specifically, in addition to lower prices, competition leads to improved product quality, not to their deterioration. The fear of losing a customer to a competitor is a sufficient deterrent to planned obsolescence. Refuting the theory of natural monopoly would discredit at the same time the theory of planned obsolescence.

In fact, a monopoly in itself is not a threat if it is unable to charge a monopoly price (Mises, [1949] 1996, pp. 278, 357-391, especially p. 370). But such a monopoly can not arise in a free market. As the economy becomes more complex and advanced, the products will become more and more heterogeneous, the differentiation being more pronounced at the consumer level than at the producer level, and this, with the increase of the level of education that facilitates the discrimination between products (Rothbard, [1962] 2009, pp. 666-667, footnote 28). It follows that the establishment of a monopoly price is not necessarily easier in an advanced economy even in spite of information asymmetries. Competition will not even allow monopoly prices to be settled (pp. 681-686), the concept being itself completely meaningless since it is perfectly impossible to detect the so-called “monopoly price” (pp. 690-695, 700-702). Even economies of scale in a context of inelastic demand is not an obstacle to competition (Rothbard, 1962, ch. 9 and ch. 10).

Another line of attack against the theory of monopoly prices would be to consider the response of the prices of factors of production when a large firm reduces its supply of consumer goods in order to increase prices. If this happens, its own demand for factors of production, necessary for the production of consumer goods, will decrease. Eventually, the prices of factors of production would decline, providing an opportunity for competing firms which can now reduce their production costs. They are thus able to lower their prices and challenge the monopoly (in a cut-throat competition). Even imagining an unrealistic scenario where the monopoly substitutes for the competitors to the purchase, on a regular basis for preventing the prices from falling, of all the factors of production in excess, the accumulation of those ‘idle’ productive resources is a great loss because such amount exceeds what he needs to replace his existing capital goods. It would be far more advantageous to increase its production to capture a larger market share, causing lowered prices due to reduced average cost of production, making a big-scale production more profitable.

It should be kept in mind that regulations (taxes, price controls, pro-union legislation) could promote obsolescence. A tax increase would lead, for example, to an increased difficulty in providing inputs that would otherwise have improved the quality of the products. Reisman has an interesting discussion on planned obsolescence (Capitalism, 1996, pp. 214-216) where he explains why an industry would greatly increase its profit if it produces longer-lasting goods, except when production cost exceeds the benefits to produce more durable items.

We have yet to deal with one key argument of the documentary. The Epson chip inside of the printer, programmed to “break” the machine after a predefined number of printed pages, is somewhat obscure. At first glance, it is clear that this is an attempt to encourage consumers to buy more printers. But companies have no reason to degrade the printer, to the extent that most of their profits come from the sale of ink cartridges. It would be silly to block the printers if they really want to encourage the purchase of their cartridges.

Even if this obsolescence was planned, as this Epson chip suggests, it does not mean that all companies have an incentive to adopt the same strategy. Especially if this strategy is not profitable in the long term, which means that such a phenomenon is in any case quite ephemeral.

If firms planned to degrade their products, this means that their demand for factors of production (labor, natural resources...) will automatically increase since they have to increase the production of consumer goods. Then, the prices of those factors will also increase, leading to an increase in costs of production. Not in profit.

Needless to say, in the long run, such a strategy is unlikely to be profitable. If obsolescence persists, it is not “planned”. The most probable interpretation is that preferences are shaped by cultural and technological changes, such that firms must respond to the ever-changing consumers’ preferences. In times of frequent technological improvement, it is also desirable for manufacturers to avoid dumping more resources into making products last past their usefulness. Shorter lifespan can even guard against uncertainty. Landsburg (1999) mentioned an interesting case:

What brings all this to mind is the recent controversy over Monsanto Co.’s development of infertile seeds–seeds that yield crops that don’t reproduce so that farmers have to buy new seeds each year. From the farmer’s point of view, the opportunity to buy infertile seeds can be a great boon. Instead of paying $100 for seed that should last 10 years, you pay $10 for new seed each year, which insures you against the possibility of a disastrous and expensive crop loss.

For the same reason planned obsolescence cannot induce people to buy more and more, ads cannot encourage consumption as a whole. This is because the rise in consumption without any rise in savings will lead to an increase in prices of factors of production, and thus an increase in costs of production, since no more resources are devoted to produce more capital goods allowing an increase in production of consumer goods. It is only when people decide to consume less and save more that the prices of goods will become cheaper, allowing them to purchase more consumer goods in the future due to the enhancement of productive capacity by a prior increase in savings. This is clearly at odds with the assumption that ads can induce more purchases. Instead, one must ask why private savings is low, whether it is due to social benefits or not.