The Evolution of Human Cooperation According to the Supernatural (Divine) Punishment Hypothesis

Several studies have now investigated the question of the impact of believing in a "mean" God versus a "kind" God, one who punishes versus one who forgives. And sometimes the belief in hell versus heaven. These beliefs then are correlated with diverse social outcome measures. This needs to be discussed because the results are not what we would necessarily be tempted to believe. The reason of why this happens also deserves elaborate explanations.

1. Theoretical grounds.

The divine punishment, more commonly named SPH, is believed to be the most powerful strength acting to make people cooperate and avoid what is called among the economists the public good problems, or commonly known as the tragedy of common goods and prisoner's dilemma, considered by most economists as market failure. This is a motivating topic, since we are usually told by most economists that cooperation can and should be enforced by government regulation, and on the other hand we are told by some (minority) austrian economists that free market provides a more efficient resource allocation. Now, we are told that what we need the most is religion. Johnson (2006, 2011) and Shariff et al. (2009) are among proponents of these ideas.

In small-scale social groups restricted to close genetically related individuals bound by kin selection, the religion (and gods) is not strongly connected to morality. One explanation, they say, is that shirking, free-riding, and defection, are much more likely in huge societies where anonymity is the norm. It is believed that a stronger figure of authority is needed in order to better discipline the individuals living in big societies.

Institutions, such as governments, are said to be not dissuading enough because of second-order cheatings, e.g., not being able to administer the punishment. Moreover, some people may believe to be able to escape from the government supervision. They will not put an end to their misdeeds. The idea of God, as figure of punishment, has no such costs. People who believe in God know already there is no way to escape from the supervision of God. The cost of their misdeeds will be paid in afterlife. The fear of death and the thought of not being able to go to heaven thus can easily be manipulated in order to ensure strong bonds and cohesion.

Once again, this is not to say other factors are not important. God aside, the most biggest fear of most humans is certainly the idea of being rejected by their own community, their own people with which they live. Thus, the opinion of the majority, perhaps better called tyranny of the majority, exerts a strong pressure against the act of free-riding.

As several proponents stated (Salter, 2007, ch. 6), what is good at the individual level may not be good at the group (community) level. Thus, it is needed to sacrifice one's own selfishness and interest in order to preserve the interest of the group, including its genetic interests (Salter, 2007).

Such ideas would be said to be provocative since they imply that individuals have the sense of morality not because they agree with being moral and honest but only because they are afraid of their consequences. Fear is the driving force behind morality. In other words, even when people act morally, they are still selfish. Once again, the idea does not necessarily implicate that people always act morally because they are afraid about retaliation. What the theory seems to imply, although none of the authors mentioned so far advanced the idea directly, is that a large portion of human behaviors is not driven by any sense of morality but only by fear. Otherwise, the idea of moralizing Gods needs not to expand with the size of community.

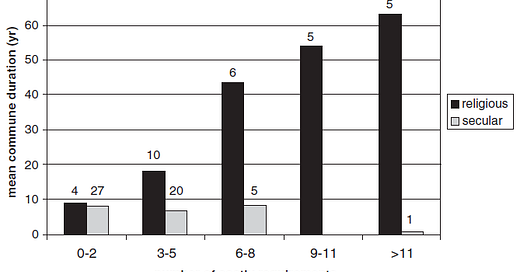

There is some (modest) evidence that SPH may be at work, even today. Sosis & Bressler (2003) examine 83 19th-century US communes having different ritual requirements (about behavior and habits, see Table 1) imposed on their members, which ideologies are "religious" versus "secular". In table 4, it is observed in the logistic regression model that religious communes are less likely dissolve themselves, while in the model with religious*requirement interaction, the large main effect of religiosity disappears under the effect of the interaction, which means that costly requirements solely explain the success of religious communes (in lowering dissolution) over secular communes. As predicted, there was no meaningful secular*requirement interaction at all. In table 5, it is observed that the communes with more stringent religious requirements show improvement in group commitment. The probability of commune dissolution owing to either internal dispute or economic failure (the dependent var) is not moderated by religious (stringent) requirement (independent var) but religious communes are still less likely to dissolve themselves, as compared with secular communes. Overall, the data seems to support SPH. In the regression models, there seems to be few controls for potential confoundings but the fact these communes were compared within the same country makes confounders such as cultural differences less likely to play a role.

Roes & Raymond (2003) examine 186 societies around the world and found that belief in moralizing God(s) correlates with society size, and independent of geographical areas, or population density, or class stratification, or (classical) religions type although it becomes smaller in this case. Nonetheless, there is an interaction between moralizing God and caste stratification, thus suggesting that religion is stronger for where inequality is made salient. Also, moralizing God is not associated with fewer internal conflicts. It must be noted that cultural differences between countries are quite large and controlling fo these factors can have an impact of the relationship, but adding more controls in regression models only makes sense if these cultural and socio-economic factors are largely independent of God's belief. Otherwise, any attempt to maintain these variables to be equal across societies would also fix God's belief to be equal (to some extent).

Johnson (2005) use the same sample of 186 societies (from SCCS database). Several (desirable) social variables, e.g., money exchange, credit source, community size, police, (less) taxation paid to community, sharing of food, sanctions, correlate with "high God" and most correlations were in the predicted direction (except internal warfare which should have been negative rather than being actually positive). When these variables are entered altogether into multiple regression, they don't seem to have independent effects.

But now, if religion has been driven human cooperation all this time, what is the nature of the factors at work ? Shariff et al. (2009) attempt to explain the evolutionary processes purely in terms of culture. They seem to refuse the possibility of genetically-driven pathways. Shariff et al. (2009) begin to explain :

As a result, the evolutionary mechanisms of kin selection and reciprocal altruism have favored the emergence of altruism toward relatives and in reciprocal dyads or very small groups. Among humans, indirect reciprocity, wherein reputations can be ascertained by third parties rather than only through personal interactions, has increased the number of potential dyadic partners. Indirect reciprocity, however, does not increase the size of the cooperative group and operates effectively only so far as these reputations can be very reliably transmitted and recalled for most potential partners (Henrich & Henrich, 2007). None of these mechanisms permits large-scale cooperation.

Thus, though humans have evolved to use each of these strategies, the extent of human social interaction was still, for much of human history, limited to cooperation in very small groups. There are two ways in which human sociality was limited. First, kin selection and reciprocity are limited to small cooperative units of two or three individuals and cannot explain interactions in which large of numbers cooperate in the same unit, such as in warfare, group hunting and food sharing, recycling, blood donation, voting, or community house construction. Second, because groups were likely regulated by reputational information and personal relationship, this caps the size at which individuals can maintain a generalized sense of trust toward fellow group members. Extrapolating from neocortex size, Dunbar (2003) estimated that human brains were designed to manage ancestral groups of about 150 members. Beyond this number, unfamiliarity abounds, trust disintegrates, reciprocity is compromised, and groups divide or collapse. Although this specific number can be disputed (e.g., Smith, 1996), it is apparent today from the size of modern human settlements that solutions have been found to the limitations that used to make such settlements unstable. This effect is demonstrated in ethnographic work in part of New Guinea, where villages routinely split once they exceed about 300 people (i.e., 150 adults). Tuzin (1976, 2001) detailed the historical emergence of an anomalous village of 1,500 people and showed how culturally evolved beliefs about social organization, marriage, norms, rituals, and supernatural agents converged to maintain harmony and galvanize cooperation in a locale where this scale was previously unknown.

... As background, the religions of small-scale societies including foragers often do not have one or two powerful gods who are markedly associated with moral behavior (Roes & Raymond, 2003). Many gods are ambivalent or whimsical, even creator gods. Gods, in most small-scale societies, are not omniscient or omnipotent.

This idea is quite correct. But their attempt to explain the process in terms of purely environmental factors fails badly. Contra Shariff et al. (2009), religious commitment cannot be made possible if the individuals in the group did not already have some sense of self-sacrifice for the interest of the group, due to earlier evolutionary processes resulting in the lower successful of the most selfish individuals to pass on their genes by reproduction. This has been explicited by Hart (2007, p. 37). The persons who attempt to save (and succeed in it) a close relative will have more surviving genes (the relatives plus his own genes) than persons who act selfishly and, as a consequence, will be favored by natural selection. Different selection pressures owing to difference in climate condition may explain the emergence of different religious habits because of the emergence of these genetic differences between populations. Religion with stronger commitment is expected to be found in groups where genes that dispose people to foster within-group cooperation are favored, thus helping to consolidate those genetically-induced traits. Obviously, if people choose cultural habits mostly in line with their own genetic predisposition, the resulting genetically-induced cultural background could produce a correlation between genotype and environment, the so-called rGE, most likely of active type.

Schloss & Murray (2011) doubt that the fear of supernatural forces was necessarily adaptive, and believe that non-believers who fake to be believers of God would incur the costs associated with fake acting. In addition, they believe that the human mind is biased toward under-estimation of risks. But, as Johnson (2011) remarks, there is also a benefit associated with religious conversion such as the participation of joint social activities which would surely more than counterbalance the disadvantage to endorse religious beliefs. More importantly, the simple fact that the majority of the community believes in God is in itself sufficient to induce religious belief. It is well known that the human mind is biased towards convergence to the views held by the majority. The Asch conformity experiment is the best illustration of this idea. The more people hold religious beliefs, the more likely the others will join, sooner or later. The majority thus exerts some sort of social pressure against the individual, similar to the typical situation described in the idea of the tyranny of the majority.

2. Empirical findings.

We will begin to present several studies showing relationship between religion and desirable social behaviors, the kind most needed for group cooperation.

Randolph-Seng & Nielsen (2007) conduct 2 priming studies on undergraduates (N=52, N=54) for which the primed words focus on religion concepts and the outcome of interest was honesty. They use Hartshorne & May’s (1928) circle task to measure honesty. The task required participants to write specific numbers in small circles while alone in a room with their eyes closed. Participants were induced to cheat by being provided with unrealistic expectations of performance and additional extra credit for high performance. The result was in the expected direction. For both students, participants primed with religious concepts are much more likely not to cheat.

Gervais & Norenzayan (2012) performed 3 priming studies on undergraduates. In study 1, the 277 participants (age=20) were presented with 13 adjectives (e.g., loving, distant) which participants were randomly assigned to rate based on different criteria. In the "Control" Prime condition, participants (N=81) rated the adjectives based on their perceived frequency in everyday speech. In the "God" Prime condition, participants (N=114) rated how well each of the 13 adjectives describe God. In the "People" Prime condition, participants (N=82) rated the extent to which each adjective describe the way that other people view them. They then complete a public self-awareness and religiosity questionnaires. Those who have a high belief in God shows larger self-awareness in prime situations, as evaluated by Cohen's d effect size of 0.45 and 0.67 for God-control and People-control comparisons. However, those who have a low belief in God shows lower self-awareness in when primed with God concepts, as the Cohen's d effect sizes are 0.38 and 0.42 for God-control and God-People comparisons. There was virtually no difference in the control (M=11.51) and People priming (M=11.67). Their interpretation reads as follows :

Aside from the surprisingly high public self-awareness in the Control condition, however, the pattern of results was consistent with the interpretation that, for Low Believers, thinking of God was not psychologically comparable to thinking of the social judgment of their peers. In other words, the initially puzzling pattern of results likely has more to do with Low Believers scoring high on public self awareness in the control condition than with any inconsistency regarding the effects of our two theoretically-relevant conditions where we juxtaposed thoughts of God and human social judgment.

In study 2, only 38 undergraduates (age=20) are studied, with 21 assigned in God prime and 17 assigned in control condition. They have to unscramble ten sets of five words by dropping one word and rearranging the others to form a sentence. In the God concepts condition, five of the sentences contained target God concept words (God, spirit, divine, prophet, sacred), whereas in the Control prime condition the words were unrelated to religion and did not have a coherent theme. Self-awareness score again increases substantially for God prime (M=13.57) condition versus control (M=9.71). Belief in God has no effect and it does not interact with God priming, but they rely on the p-values, a useless statistics, instead of effect size. Sampling error may explain why belief in God has no moderating effect on God priming.

In study 3, just 58 undergraduates (age=20) are studied, with 32 assigned in God prime and 26 in control condition. They indicate whether or not 11 statements are true of them. The statements concern either common, but socially undesirable, actions (“I am sometimes irritated by people who ask favors of me”), or unrealistically positive actions (“No matter who I'm talking to, I'm always a good listener”). The participants were thus forced to choose between giving an honest answer to each item, or to give a socially desirable answer. Among high believers in God, the God priming (M=4.93) shows larger social desirability score than in the control (M=2.79). Among low believers, the god (M=3.71) and control (M=3.67) conditions do not even differ.

A suspicion test is always needed in such studies. Hopefully, they affirmed that no one seemed to be aware of the real purpose in study 2 and 3, despite the religious priming, not hidden to them. But a suspicion test has not been conducted in study 1, apparently.

Thus, a bunch of studies confirm the relationship between religiosity and several desirable outcomes that are crucial for the development of communities, and not only in terms of size. Now, we will discuss the studies that show evidence of religiosity-punishment association.

McKay et al. (2011) conducted a priming study, which consists in displaying subliminal message on the screen in order to induce certain ideas to the participants (N=304, age=22). They use a two-player game where they are paid for their participations plus the total money earned in the game. In first stage, player A is given the choice to select the fair (e.g., 150;150) or unfair (e.g., 590;60) share of allocations or points (where 1 point equals 0.28 CHF Franc Suisse) for players A (left number) and B (right number). In second stage, player B is informed about the two options presented to A but has no information about what A has chosen. But B was given, for each option, the possibility to spent her points out of her allocation in order to punish player A by reducing her payoff. Each point spent by B reduces the money of A by 3 points. For example, if the allocation chosen by A is (590;60) and B spent 30 points, then A's money is reduced by 590-(3*30)=500 points and B's money is then 60-30=30 points. The researchers argue that knowing the response of A would not affect the behavioral patterns of B, i.e., the results are expected to be identical, assuming anonymity is preserved. The religion primes are : divine, holy, pious, religious. The punishment primes are : revenge, punish, penalty, retribution. The religion-punishment primes are : divine, revenge, pious, punish. The control primes are : northeast, acoustic, tractor, carton. Subliminal messages appear between the 2 stages of the game. Then, religion questionnaires are given, i.e., religious affiliation and a question regarding whether or not they have made donation to a religious organization during the last year.

None of the primes had large effect, either for fair or unfair choice. One interaction, however, seems to display a very large effect, religious_donation*religion_prime, but only for the unfair choice. No other donation*prime interactions were meaningful. The result, thus, seems to suggest that religious people tend to reinforce punishment when unfair choice is committed. The authors write in this regard :

How are we to account for these results? In line with Shariff & Norenzayan [17], we consider two possible proximate explanations. The first is that religious primes activate the notion that one’s behaviour is observed by a supernatural agent. In this case primed participants punish unfair behaviours because they sense that not doing so will damage their standing in the eyes of a supernatural agent. Recent studies suggest that even very subtle cues that one is being watched, such as stylized eyespots on a computer screen, can affect giving behaviour (e.g. [28,29]; cf. [30]). Some authors have suggested that such cues match the input conditions for evolved mental mechanisms that detect when one’s behaviour is observed [28]. Religious primes might likewise function as input for these mechanisms [17].

... If an individual believes that in order to avoid punishment herself she needs both to adhere to and to uphold cultural norms of fairness, then religious primes may affect punishment behaviours both by evoking a sense of being observed and by directly activating the relevant norms.

Laurin et al. (2012) predicted that experimental behavior would reflect real world behavior. Religious people are expected to rely less on individual or governmental intervention in punishment if they believe God will administer the final punishment to the defectors. In study 1, each undergraduate participant (N=20) imagines a dictator game involving 3 players, a sort of Third-Party Punishment Game (TPG), where player A is given 20 dollars and is free to share as many he wants with player B. Each participant imagines being the player C, who is given 10 dollars and who is free to spent the money (each dollar spent causes 3 dollars less in player A) to punish the unfair sharing of player A. They must imagine how much they would spent their money to reduce A's earnings for each possible way the player A can divide the money with player B. It was found that the players C with the strongest belief in a powerful (interventionist) God punishes the less. Conservatism correlated with religiosity but did not mediate religion-punishment association. In study 2, they recruit 55 undergraduates to participate in the 3 partners dictator game, with the particularity, here, that all participants play the role of player C although they were told they can endorse the role of either A, B, or C. Furthermore, they sought to study the causal effect of priming the concept of God by giving the (intervening) God belief and religiosity measures before DG (salient) for some participants and the (intervening) God belief and religiosity measures after DG (non-salient) for the other participants. Those who were given the God belief question before the DG punish less (β=-0.90) but no such effect was apparent (β=-0.12) among people for whom God beliefs were not salient (i.e., questions given after DG). Similarly, when religiosity was salient, more religious individuals punish more (β=0.90) but no such effect was apparent (β=-0.11) among individuals for whom religiosity is not salient. This is a strong suggestion of causal effect. Political orientation has no effect on the results. In study 3, they recruit 72 US residents who read about a corporate executive who was stealing from his company to maintain his gambling habit. Next, they indicate how many of their tax dollars they would like to see devoted towards state-sponsored (a) catching and (b) punishing of persons like this executive. This question serves to measure state-sponsored punishment. Consistent with studies 1 & 2, when God belief is made salient (non-salient), those who see God as a strong figure endorse less (more) state-sponsored punishment. For religious measures, the pattern was the opposite, with salient (non-salient) religiosity producing more (less) endorsement in state-sponsored punishment for more religious individuals. In study 4a, belief in strong God correlates with God's responsibility for distributing punishment (β=0.50), with perceived appropriateness of punishment, e.g., bad deeds deserve punishment, (β=0.19), but not with beliefs in free will (β=-0.07), among 25 participants. In study 4b, the researchers replicate study 1 with 76 US residents, and new variables. When attribution to God is salient, people who attribute more responsibility to God for punishment punish less (β=-0.48) but punish more (β=0.54) when the measure is non-salient.

Shariff & Norenzayan (2011) conduct an experimentation involving cheating. The 61 undergraduate students (mean age, 20) are given a computer-based test, specifically, reading comprehension task and math task (which is actually the cheating measure). The possibility of cheating on the test is made apparent by a sort of "glitch" which makes the response appearing briefly on the screen just after the question appeared, on the condition the participants do not press the spacebar immediately. They were obviously asked to do the task with honesty, i.e., by pressing the button "spacebar". Good news, they have cheated. And we can see how the results in study 1 look like :

The God questionnaires are given after the test (the contrary would have been problematic especially without dilution) with a few other questions rearding ethnicity and religious devotion. Thus, the participants can easily guess what the purpose of the test was after study 1 is done. The result, anyway, remains truly interesting.

Because they suppose these correlations can be mediated by other factors (e.g., personality), they repeat the same experience with the same persons in study 2, giving them another set of questions related with the figure of God, belief in God, and other questions susceptible to predict cheating. As mentioned above, if only a few questions have been given to them, the participants will guess the purpose of the study and this will nullify the validity of the study. The god questionnaire must be "diluted" into a mass of other questionnaires, so as to make the connection between god and the cheating experiments very unlikely. It is important that the intention of the researchers can be hidden from the subjects. Hopefully, the authors seem aware of this, as they dilute the God questionnaires into others, irrelevant ones, not included in the regression analysis, several days before the experimentation for study 2. The time interval between the questions and the test renders the guessing of researchers' intention more difficult, but the very fact that the God questionnaire has not been diluted in study 1 could have invalidated the results in study 2, unless the participants believe that the addition of a new set of questions was relevant for the new study even though it does not, i.e., that the purpose of study 2 was different than that of study 1. One possible way to check it is to give a suspicion probe test that asks the participants to guess the purpose of the study. The researchers have dropped those who correctly guess their intention. Nonetheless, it is unfortunate they haven't correlated these measures across the two studies, checked and compared their means and standard deviations. If the scores and correlations show great divergence, it renders interpretability somewhat difficult.

Anyway, the correlation between protective God and cheating was still present in study 2. The correlation between the figure of God (or belief in God) and cheating was -0.58 (or -0.12). The authors claimed there was no interaction between belief in god and the figure of god (mean vs. kind) because the p-value was not significant. This is because the sample size is small. The beta coefficient was -0.63, even higher than the main effect, which was not reported in the model including the interaction. This would have been an importan information because if the main effect disappear with the presence of interaction, it suggests that all of the effect is due to the interaction. The result shows that the negative effect of a protective God (with regard to cheating) is reinforced if people are stronger believers (in God).

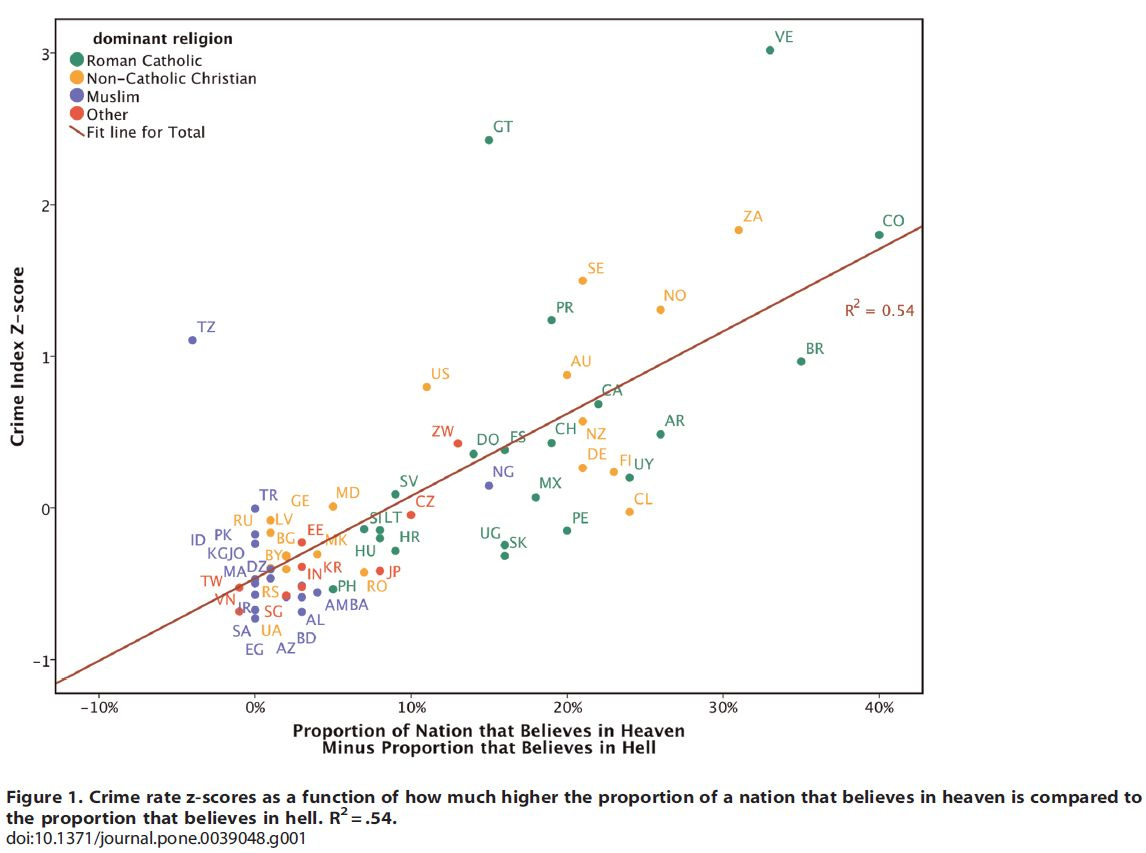

Subsequently, Shariff & Rhemtulla (2012) use the World Values Survey (WVS) and European Values Survey (EVS), data across nations. Multiple regressions are used. The dependent var. are diverse measure of criminality, such as assault, motor, burglary, drug, homicide, human trafficking, kidnapping, rape, robbery, theft, and finally, average of all crimes. The independent var. are religious attendance, belief in heaven, belief in hell, population imprisoned, Gini, GDP/capita, life expectancy, urbanicity, belief in God, conscientiousness, neuroticism, agreeableness, roman catholic, other christian, muslim.

When belief in heaven and in hell are the only independent var., for 1 SD increase in heaven (hell) is associated with almost 2 SD increase (decrease) in average crime. When all the covariates mentioned above are included, the Beta coefficients are 1.820 and -1.698, respectively. In other words, they are not affected this much. Belief in God and religious attendance have a coefficient of -0.475 and -0.124. The independent effect of attendance on crime reduction is apparently weak, but if it correlates with belief in hell/heaven, then the correct interpretation will be that the entire effect of church attendance (on crime) consists only of common effect that has been partialed out, thus the full extent of attendance has been hidden. The remaining variables had weak effect as well, perhaps for the very same reason. The next analysis involves correlation between crime and belief in hell/heaven by religion types, as depicted below.

Given the data points, the correlation seems to operate within each religion type, except muslim. But, as can be seen, this is due to the insufficient variance in the scores of belief in hell/heaven for. When severe restriction in variance is effective for any of the variables to be correlated, null correlation must be expected.

The main problem with the result is the involvement of cross-national comparisons. Countries certainly differ meaningfully in a large panel of characteristics, not just the ones they have included in their regressions. Furthermore, no interaction analysis had been conducted. Probably, the analysis provides only a modest support for the SPH.

In a sample of 41 countries, from the WVS data, Barro & McCleary (2003, Table 4) found belief in evil to be much more correlated with economic growth than is belief in heaven whether both are entered together or independently, and the inclusion of different types of religion does not reveal such specific effects. Independent of belief in hell or heaven, church attendance correlates negatively with GDP growth, in other words, the portion of attendance that is unrelated with belief in hell tends to reduce economic growth, and the authors are fully aware of this apparent intriguing result (p. 38). The pattern of growth holds after controlling for reverse-causation, which is done by including instrumental variables such as the existence of a state religion, the presence of government regulation of religion, the extent of religious pluralism, and the composition of adherence among the main religions, all highly correlated with attendance and beliefs, thus suggesting a stronger plausibility for the causal effect of attendance/beliefs. They hypothesize the following :

Church attendance might also proxy for the influence of organized religion on laws and regulations that affect economic incentives. Adverse examples would be restrictions on credit and insurance markets and general discouragement of the profit motive. Positive forces might include legislation and regulation related to fraud and corruption.

Overall, these research are coherent with the idea of Johnson & Bering (2006) that punishment is more effective than rewards. Indeed, carrots encourage people to cooperate but do not prevent all people from cheating.

If religion is socially important, one would ask what factor best predicts fidelity in religion. Using the Baylor Religion Survey (BRS 2007) for the US, Martinez (2013) conduct regression models with 4 measures of religious commitment, namely, church attendance, self-perceived religiosity, monetarily giving to a religious organization, faith sharing, successively, as a dependent variable. The independent variables of interest were belief in supernatural evil, authoritarian god, biblical literalist, friends in congregation. Other controls include sex, age, white non-hispanic, being married, education, income, south region, as well as a categorical variable which involves evangelical protestant (reference value), black protestant, mainline protestant, catholic, jewish, other, none. For church attendance and self-perceived religiosity, belief in authoritarian God has a Beta coefficient of 0.112 and 0.146. For the other two dependent var., authoritarian God shows no correlation at all. When belief in supernatural evil is included, the effect of authoritarian God on attendance and self-perceived religiosity has only a Beta of 0.047 and 0.060. The belief in evil has a Beta coefficient, for the 4 measures of religious commitment mentioned above, respectively, of 0.246, 0.430, 0.211, 0.134 (b coefficient in poisson regression). These effects are not small. What this suggests, then, is that the wrath of the Evil is a more effective way than the wrath of the God to elicit devoutness and loyalty among the individuals. But this would be a misinterpretation of multiple regression. In such models, the predictors have both a common and independent effect, and the coefficients only estimates the independent (not full) portion of the variables, and by removing all of the common effects. If belief in God disappears following the inclusion of Evil, it only means that the total effect of God is entirely subsumed into the common effect of Evil which is also removed in the estimation of the independent (not full) effects of the predictors, and thus no effect of God is left because the full effect of God consists almost of common effects. However, if belief in God causes belief in Evil, rather than the reverse, then the regression cannot evaluate the full effect of God because it was partialed out. Thus, the independent effects of predictors in regression cannot be said to be comparable, even expressed in standardized Beta coefficients. Nonetheless, the mere fact that belief in Evil has an independent effect, unlike God, suggests that Evil and God have different correlational structures with regard to commitment. The theory advanced by Martinez is presented as follows :

Stark and Bainbridge (1987) briefly discuss the importance of this belief and hypothesize that the belief in supernatural evil is a vital component of religious commitment. They offer the rapid decline within the liberal Protestant tradition as anecdotal evidence for the necessity of religions to maintain at least two ‘‘god’’ figures. They contend liberal Protestantism’s departure from the belief in supernatural evil is a contributing factor to their decline in popularity.

Stark and Bainbridge (1987) propose that the ability to have meaningful exchanges with a ‘‘god’’ figure requires that the god be predictable in ‘‘His’’ or ‘‘Her’’ exchanges with humans. The bifurcation of god figures into ‘‘good’’ and ‘‘evil’’ allow humans to be more certain of what they should expect to receive from their god, and therefore more committed to their religion. They go on to say that the desacralization of supernatural evil, quickly leads to a situation where a religion cannot plausibly offer supernatural compensators as part of its cultural system, giving the religion little to offer most people. Consequently, Stark and Bainbridge argue that a strong correlation should exist between the individuals who believe in supernatural evil and those who are committed to their religion.

This hypothesis is very tempting, and quite provocative, because it suggests (although not affirmed by the author) that part of the decline in religious beliefs, today, is due to the fact that people stop believing in the Evil.

Other studies don't use the concept of God but simply elicit the idea of being observed, and sometimes (as explicitly stated by the investigators) by an invisible force. Because the idea of divine punishment is not made clear to the subjects, it is quite possible that the impact of the treatment effect is somewhat under-estimated. These studies are still relevant in the sense that the feeling of being observed encourage sharing, cooperation, honesty, and other desirable social outcomes.

Piazza et al. (2011) studied children (39 5/6-year-olds, 29 8/9-year-olds) who were invited to play a game, throwing "Velcro" balls at a target and win some prizes (e.g., toy, diary, art supplies), under 3 restrictions, 1) using their non-dominant hand (having a wristband), 2) when facing away from the target and 3) without crossing the white line. The scene is depicted in the camera shot below, as they are secretly filmed in action. Three conditions are constructed. The first is when the children are told they are being watched by an invisible "Princess Alice" sitting on a chair (see below picture). The second condition is when an adult is sitting on the chair, observing the children. The third condition is the unobserved situation. There was no difference in cheating tendency between the first two conditions, but as expected the children were much more likely to cheat on the third condition. Interestingly, among the children under Princess Alice condition, the skeptical children who have cheated did so only after they managed to confirm the absence of Alice by inspecting the chair (as in the camera shot below).

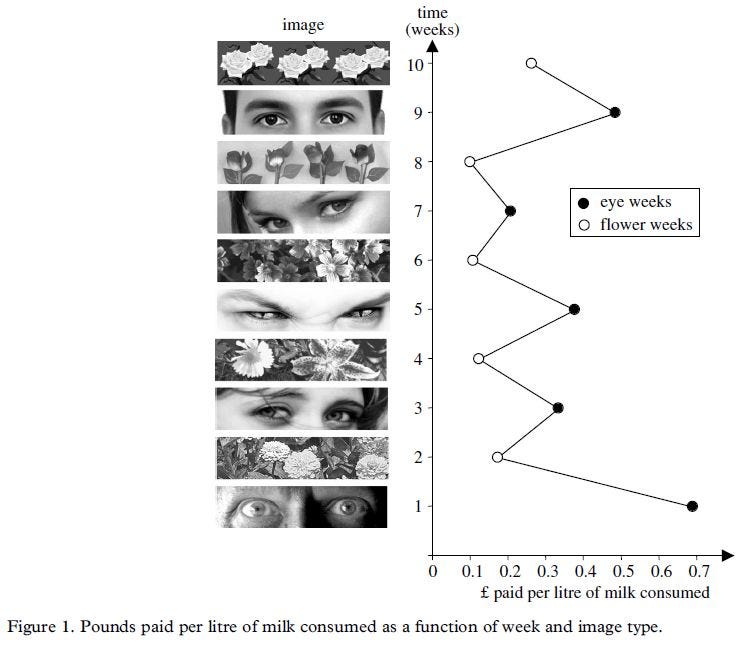

Bateson et al. (2006) examine 46 persons, apparently university students, who pay money for drinks through a so-called "honesty box". Pictures of eyes (experimental condition) or pictures of flowers (control condition) in a notice (150x35mm banner) are shifted each week during the period of experimentation. The persons who were facing pictures of eyes (shots taken from real persons) payed 3 times more money than those facing the picture of flowers.

Haley & Fessler (2005) conducted what is called the "dictator game" (single-round) where the players (248 undergraduates aged 22) are paired two by two and share money through a computer. The procedure, however, is misleading in its name because it is not really a game. Player 1 has a the role of dictator or decision maker, whereas player 2 the role of a mere receiver and has no possibility to influence the outcome or the decision of player 1. Specifically, player 1 is given 10 dollars and must decide if he shares any money at all and, if so, how much. The participants do not know which one they are paired with because the procedure takes place in total anonymity. 5 conditions are created; 2 controls (with and without sound-reducing earmuffs) and 3 experimentals (eyespots with sound, eyespots without sound, skewed eyespots). The research hypothesis was that under the condition of stylized-eye-like shape appearing on the desktop background, the player 1 will give more money, when compared with players under control conditions. Furthermore, it was predicted that when sound is added to the eyespots, the participants will give even more. It was also expected that the eyes that look directly toward the player will induce the dictator to share more money. As displayed in table 1 the average of all 5 conditions produce a share of US$ 2.85. And only 69.4% of the players accepted to share something, i.e., the remaining 30.6% share nothing at all and take all the money. The players in no-eyes with and without sound shared 2.45 and 2.32 dollars whereas players in silent-eyespots, skewed-eyes, and nonsilent-eyespots shared 2.72, 3.00, and 3.79 dollars. The averaged (3) experimental and (2) control conditions show a sharing of 3.14 and 2.38 dollars. The authors argue that the increase in dollar sharing, following the experimentation, was mainly due to the decision of the player to give or not to give any dollar at all, rather than by an increase in shared dollars. They warn about the necessity of complete anonymity for DG to be valid because the opposite causes participants not to act selfishly due to reputational concerns.

Shariff & Norenzayan (2007) conduct a classic dictator game (DG) on 50 students (age=20) under anonymity for their study 1. Before the beginning of DG, the subjects were required to unscramble 10 five-word sentences, dropping an extraneous word from each to create a grammatical four-word sentence. For example, "felt she eradicate spirit the" would become "she felt the spirit," and "dessert divine was fork the" would become "the dessert was divine." Five of the scrambled sentences contained the target words spirit, divine, God, sacred, and prophet, and the other 5 contained only neutral words un- related to religion, and forming no other coherent concept. The subjects in no prime condition left 1.84 dollars on average whereas those in religious prime condition left 4.22 dollars on average. Because a questionnaire on belief in God has been administered (after the game) it was possible to evaluate the impact of implicit priming of God among theists and atheists. In both cases, the prime condition led to increase in dollar sharing. The effect, thus, cannot be attributed to religiosity. In a second study, they recruit a more representative sample around the Canada (N=78, age=44). The DG condition has been modified here. The subjects were led to (wrongly) believe they are alternately assigned to be givers and receivers and that they randomly happen to be givers, so that whatever decision they made would affect the following subject. There are 3 prime condition, the neutral, which has no target word, the secular-prime which targets the words civic, jury, court, police, contract, and religious-prime which is exactly the same as in study 1. The participants share 4.56, 4.44, and 2.56 dollars under the religious, secular, and no prime conditions, respectively. They argue, based on p-value, that religious prime has no effect on atheists. Because they are subjected to artifacts such as sample size and because they don't evaluate effect size, the significance test can never be trusted. Only 5 participants had suspicions about the real intention of the study. Their exclusion did not modify the results.

The dictator game (DG) has been subjected to considerable criticisms among the economists due to the high sensitivity of the DG studies' results with contextual changes (Bardsley, 2008), notably added to this the suspicions that the subjects will attempt to guess the study hypothesis and thus react accordingly by trying to act as a "good" experimental subject, and the fact that behaviors in DG experiments are sometimes not reflected in real world behaviors, but the DG has been defended as well (Rigdon et al., 2009; Guala & Mittone, 2010).

As Binmore (1998, 1999) has argued, subjects bring inside the laboratory a whole set of experiences and social cues that help them coping with what is an otherwise unfamiliar and puzzling situation. Anthropologists who have played such games with hunter-gatherers in Africa, Asia, and South America (Henrich et al., 2004) largely confirm this insight. The Orma, a group of pastoral-nomadic people living in Kenia, for instance do not fail to notice that the Public Goods game is structurally similar to the harambee - an institution used for fund-raising and other collective projects - and behave accordingly (Ensminger, 2004).

Public Goods and Ultimatum Games elicit norms of this kind in virtue of their structure, and of the fact that games with such a structure are relatively common in many societies.9 The same, however, cannot be said of the DG. The DG has a remarkably simple structure - indeed too simple (we should perhaps say “poor”) to elicit a specific norm. It is an unusual situation too, for in real life one rarely deals with “windfall money” to be shared with an anonymous stranger.

Subjects have to deal with windfall money and anonymous partners in Ultimatum Games too, but the structure of the UG is rich enough to focus their attention on power asymmetries, and therefore elicit the fairness norms that apply in such circumstances. The DG in contrast is too “thin” for that, and experimental subjects are left to puzzle over which behavior is deemed appropriate for a situation of that kind.

One weakness in some of those studies is the absence of analysis regarding religiosity interaction effect. The questionnaire is not even always given. The hypothesis proposed in these studies would be stronger if the results are divided by religiosity level or the interaction effect studied. Another evident limitation is that most studies are conducted in the U.S., and some others in european countries, but not in countries where both religious beliefs (e.g., in strong God) and cultural habits are quite different.

Henrich et al. (2010) answered the question of cultural differences. They collect a large sample (N=2148) across 15 diverse populations, from Africa, North and South America, Oceania, New Guinea, and Asia, which also include small-scale societies of hunter-gatherers, marine foragers, pastoralists, horticulturalists, and wage laborers. They administer the Dictator Game (DG), Ultimatum Game (UG), and Third-Party Punishment Game (TPG). The UG is similar to DG, except that player is now able to refuse the offer of player 1. If he does, both players receives no money. Thus, if player 2 action is only and only motivated by money maximization, he will accept every non-zero amount of money proposed by player 1. Willingness to reject the money is a measure of punishment. In this way, the action of player 1 measures a combination of social motivations and an evaluation of the likelihood of rejection. The TPG resembles DG but involves a third player, C, who must decide how much he is willing to send his money to punish A's unfair sharing with B, for any given possible money sharing. C makes the decision before A is choosing his move. Because A is aware that C can punish him (although he ignores the punishing choices made by C), A's offer measures a mixture of his social motivation and an evaluation of punishment threat. If C is a money maximizer, he will never pay anything to punish A. It was predicted that the 3 measures of fairness (indexed by the 3 games) will correlate with market integration (MI) and world religion (WR). MI is measured at the household level by calculating the percentage of a household’s total calories that were purchased from the market, as opposed to homegrown, hunted, or fished, and then averaged to obtain a community-level measure. WR is measured by asking participants what religion they practiced, and coding these as a binary variable, with “1” indicating Islam or Christianity, and “0” marking the practice of a tribal religion or “no religion”. The regression includes control variables such as age, gender, education, income, wealth, household size, community size (CS). Mean DG (money) offers correlate with MI across the (studied) populations. The result is also supportive of the view that larger communities correlates with willingness to punish in UG and TPG. SPH easily predicts that such a pattern is the result of opportunities for free-riding due to anonymity in larger communities.

3. Some (critical) comments on the studies.

As noted above, the samples are not representative, and in most cases, the professors just use students for their studies, who always are about their twenties (e.g., 22 yrs-old). Old people are rarely tested. The sum of all these sample is reasonably large but larger sample is not necessarily correlated with higher degree of representativeness. And yet, the argument does not apply here. In IQ testing, most theories certainly predict that heritability can be lowered (increased) by increasing (decreasing) the environmental variance (i.e., standard deviation) of the sampled individuals. But here, the differential effects of God's belief according to individuals' social levels seems unlikely. A person's rank or standing is of little importance with regard to God who is omniscient and omnipotent. Instead, we can suspect that the effect of God's belief may differ according to religiosity levels or cultural disparities (those prevailing between populations). And perhaps by age as well.

The experimental laboratory studies may even under-estimate the full extent of the impact of God belief because low-stakes games, such as DG, involve only a few dollars. The situation does not maximize discrimination in behaviors.

When experimental studies are conducted, one is then tempted to ask whether such results are confined to the laboratory. Concerning religiosity however, Laurin et al. (2012) cogently noted that the real world is replete with reminders of religions and Gods, such as the situations actually experienced in the laboratory.

A major, serious defect of some of the above studies is the use of ANOVA without any report of effect size. Instead, significance test is used to evaluate the presence/absence of an effect, but chi-square based indices are affected by sample size artifact, making it totally unreliable and non-informative.

We may be tempted to disprove the SPH wby invoking Islam because it seems to be related with worse outcome (e.g., Kirkegaard & Fuerst, 2014). But Islam is probably a particular case, with a different history and culture behind this religion. A test of the SPH must involve the effect of belief in evil within a religion type, not between them.

Another question is about the measured religiosity. As an example, Murray (2012) noticed that belief in God is not as highly correlated with church attendance as it should be. Thus, he believes that people believing in God but who don't attend church cannot be considered as true believers. The church attendance, according to him, is a more accurate measure. Contra Murray, however, the simple fact that believers (in God) don't go to church does not necessarily imply their faith is not genuine at all.

Still related with church attendance variable is the fact that some authors did not even try to consider its interaction effects with God belief. We can imagine the impact of belief in heaven/hell or that of a punishing/loving god is present among those who do not attend (or unfrequently) to church, but that the effect was (almost) absent among those who attend church very often. This analysis is not constantly done.

Concerning the priming studies, most of them suffer from the very fact that rarely any effort has been made to hide the religious meaning of the primed words. It is thus interesting and at the same time puzzling that most participants did not guess the intention of the study. Randolph-Seng & Nielsen (2008) argue that :

To covertly prime participants with “God concepts” a scrambled-sentence test was used. However, there seemed to be flaws in the way the procedure was implemented; specifically, it appears that an effort was not made to hide the religious meaning of all the primed words participants received (e.g., “she felt the spirit”), and some of the primed words were exclusively religious in meaning (e.g., God, sacred). To say that the prime was not conscious, care must be taken in hiding the true meaning of the concept being primed, as the researchers did with the word divine (i.e., “the dessert was divine”; see Bargh & Chartrand, 2000).

It could be argued that even though some of the primed words were used in a religious context, participants were not consciously aware of receiving the religious words. After all, the same religious scrambled-sentence test was used in the second study in combination with a suspicion probe. Such probes reflect a standard means of assessing awareness of priming manipulations (see Bargh & Chartrand, 2000). The problem here, however, lies in how the suspicion probe was implemented. First, when checking for awareness of a prime, it is essential to apply that probe immediately after measurement of the dependent variable. If awareness is not measured until the end of the study, as done by Shariff and Norenzayan (2007), then it is more likely that the probe is measuring memory as opposed to conscious awareness (Dixon, 1981). Second, and more important, participants were never explicitly asked, “Did you see any religious-related words in the scrambled-sentence test? If so, what were they?” This type of question is the most important to ask when using a suspicion probe called a “funnel debriefing” that is specifically designed to check for awareness of primed information (Bargh & Chartrand, 2000).

Although these statements are all correct, Randolph-Seng & Nielsen (2008) commit a fallacy. The simple knowledge that the experiment is related to religious belief does not prove the subjects know exactly what the researchers expect them to do, e.g., being more generous. There is indeed much more to do to improve the robustness of the current studies, but there is no strong evidence that the methodologies are deeply flawed.

4. Further reflections.

Most researchers in this field seem to believe that religion has been used by humans in order to maintain cohesion and helps further expansion of the group. The way they explain it seems to imply that religion stories, such as what is told in the Bible, are all a lie. This is quite plausible, especially because they don't even attempt to clarify this issue. Unfortunately for them, there is no evidence of it. On the other hand, there is no evidence either that those stories are the truth. That is why religion is all about belief. At the very least, it is quite possible that humans may have attempted to manipulate religion to make it serves some causes, politically related or not.

The best example I could provide is Buddhism. Most people are probably unaware of the truth. Buddhism was not a religion. The best evidence comes from the very fact that the Buddha itself was an atheist. In opposition to the doctrine of brahmanas that, he believes, is wrong. Their doctrine will never help humans to achieve the illumination. It is not because he did not believe in God. He has never responded to such questions when he was asked, even by his disciples. The reason, he argues, is because religion will not and can not save us. When asked about the existence of Gods and afterlife, he did not respond. Buddha says that whether he tells that afterlife exists, that there is a self, a soul, the persons to which he is talking will, in reaction, follow diverse religious institutions, or be troubled if Buddha answers there is none. Either way, it cannot help to find the peace of the mind. What he taught is the ultimate truth (dhamma) where the soul (atman) is not even mentioned. For one simple reason : the idea of atman was not useful to make his path toward the illumination, and he was only concerned about this path.

When people talk about Buddhism that taught compassion, what most people have in mind is actually inaccurate. This is worth noting because of the recent interest of white people for Buddhism, even though Buddhism espouses many ideas that violate the sacrosanct ideology (e.g., free will, oneself) proned by white people. The only possible reason to this is that white people are completely ignorant of the slightest thing about Buddhism. What the Buddha really taught is how to kill himself. He says all in this world is suffer. There is always suffer. There is only suffer. Here, of course, the occidentals will surely interpret the word "suffer" to mean "conflict" and "war". Missed again. What Buddha means is that the "desire" itself is the source of suffering. And the desire is caused by one's will, which is to eliminate. The only way he learned to escape the never-ending circle of suffering is by killing oneself. When he is hurt, he says we should not think about "my body hurts" "I am suffering" "someone/something makes me hurt". But instead we should say "this body is bleeding" "this is suffer". Indeed, he says we need to kill the "me", the "I", the "my", the "mine". Said it plainly, to kill the "idea of myself". What he taught exactly is how to separate the body with oneself. Try to act as if my mind, my spirit was not in my body. In brief, Buddha was a philosopher, not a religious. My main source of information comes from the writings (books) of Walpola Rahula.

Then, why Buddhism became a religion is indeed a question worth asking. Only few authors I have read made the same remark as mine but were never clear. However, they suspect, as I am, that some followers may have distorted (whether intentionally or not) the nature of Buddhism. If so, that will be in line with the expectation of the most social researchers about religious beliefs becoming "harsher" when the size of community needed more regulating systems. Using the figure of Buddha can indeed serve as a figure, name of authority, to be listened. This being said, there are recently some accounts about the possible (likely?) reincarnation of Buddha, in India (Nepal) under the name of Ram Bahadur Bomjon, as if to say those stories about the historical Buddha have some part of truth in them.

Despite the plausible hypothesis of religion(s) being manipulated, belief in god is certainly a good thing. But most people, if I understand, accept to believe in god if they find some utility. To illustrate, I have seen many times, in the realm of fiction, people who stop believing in God because something bad happened to them (e.g., their children died horribly). I have the feeling this is also how most people feel about god, but I disapprove all the speech about the nature of God. As if they pretend to understand deity. The whole enterprise is self-defeating. And yet I am quite confident that most people conceive god in this way because they don't feel like they are ready to trust or believe in God if they don't understand it (or him). If God is not seen as a guide, and if its belief does not even elicit any good feeling, I assume people don't find it useful to trust God, even if he exists. People are attached to what is good, thus want God to be attached to the idea of good. This brings them peace and calm to their mind. God is thus personified in order to satisfy human needs. But, in my view, trying to personify God is to kill him.

The decline in religion and belief in God can be symptomatic of how most individuals did see God. If they attribute misfortune to God but are later told that this is a matter of climate and seasons, thus, knowing this, most people can indeed be tempted to turn away from God, because of the way they have conceived God from the very beginning. Perhaps the best illustration of this idea is that the Catholic church did go some troubles believing, accepting the idea that the Earth moves around the sun.

Personally, I can (and I do) believe in god, but my conception is different from what white people generally conceive it. I don't conceive a God who forgives people who commit sins or a God who punishes people who commit sins because the bad and good are notions defined by humans, not by god(s). To me, a divine entity must be above the good and the evil because such conception makes sense only in the realm of the human world. What God does (e.g., the creation of the world) cannot be defined either as good or bad. Even though most individuals see it as a good thing. People perhaps want to feel God to be close to them in order to believe in God. But neither God nor heaven can be understood in these terms, and I doubt the divine can be understood by humans. It's outside the human realm.

5. References (including those not cited in the article).

Bardsley, N. (2008). Dictator game giving: altruism or artefact?. Experimental Economics, 11 (2). pp. 122-133.

Barro, Robert J., and McCleary, Rachel M. (2003). Religion and Economic Growth across Countries. American Sociological Review, 68, 760-781.

Bateson, M., D. Nettle, and G. Roberts (2006). Cues of being watched enhance cooperation in a real-world setting. Biology Letters 2:412–414.

Burnham, T., & Hare, B. (2007). Engineering cooperation: Does involuntary neural activation increase public goods contributions?. Human Nature, 18, 88–108.

Engel C. (2011). Dictator games: A meta study. Experimental Economics 1–28.

Gervais, W. M., & Norenzayan, A. (2012). Like a camera in the sky? Thinking about God increases public self-awareness and socially desirable responding. Journal of Experimental Social Pychology, 48, 298-302.

Guala, F. & Mittone, L. (2010) Paradigmatic experiments: The Dictator Game. Journal of Socio-Economics 39(5):578–84.

Haley, K. J. & Fessler, D. M. T. (2005). Nobody’s watching? Subtle cues affect generosity in an anonymous economic game. Evol. Hum. Behav. 26, 245–256.

Hart, M. (2007). Understanding human history: An analysis including the effects of geography and differential evolution. Atlanta: Washington Summit Publishers.

Henrich, Joseph, et al. (2010). Markets, Religion, Community Size, and the Evolution of Fairness and Punishment. Science 327 (5972): 1480–84.

Johnson, D. D. P. (2005). God’s punishment and public goods: A test of the supernatural punishment hypothesis in 186 world cultures. Human Nature, 16, 410-446.

Johnson, D. D. P. (2011) Why God is the best punisher. Religion Brain Behav 1: 77–84, Commentary in, Schloss, J.P., & Murray, M.J. (2011). Evolutionary accounts of belief in supernatural punishment: a critical review. Religion, Brain & Behavior 1:46-99.

Johnson, D. D. P., & Bering, J. M. (2006). Hand of god, mind of man: Punishment and cognition in the evolution of cooperation. Evolutionary Psychology, 4, 219–233.

Laurin, K., Shariff, A. F., Henrich, J., and Kay, A. C. (2012). Outsourcing punishment to god: Beliefs in divine control reduce earthly punishment. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 279, 3272–3281.

Martinez Brandon C. (2013). Is Evil Good for Religion? The Link between Supernatural Evil and Religious Commitment. Rev Relig Res, 55:319–338.

McKay, R., Efferson, C., Whitehouse, H., and Fehr, E. (2011). Wrath of God: Religious primes and punishment. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 278, 1858–1863.

Piazza, J., Bering, J.M., & Ingram, G. (2011). “Princess Alice is watching you”: Children's belief in an invisible person inhibits cheating. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 109, 311–320.

Randolph-Seng, B., & Nielsen, M. E. (2007). Honesty: One effect of primed religious representations. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 17, 303–315.

Randolph-Seng, B., & Nielsen, M. E. (2008). Is God really watching you? A response to Shariff and Norenzayan (2007). The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 18, 119-122.

Rigdon, M., Ishii, K., Watabe, M., & Kitayama, S. (2009). Minimal social cues in the dictator game. Journal of Economic Psychology, 30, 358–367.

Roes, F. L., & Raymond, M. (2003). Belief in moralizing gods. Evolution and Human Behavior, 24, 126–135.

Ruffle, Bradley J., and Sosis, Richard (2006). Cooperation and the In-Group-Out-Group Bias: A Field Test on Israeli Kibbutz Members and City Residents. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 60, 147-163.

Ruffle, B. J., & Sosis, R. (2007). Does it pay to pray? Costly ritual and cooperation. The BE Journal of Economic Analysis and Policy, 7, 1–37.

Schloss, J. P., & Murray, M. J. (2011). Evolutionary accounts of belief in supernatural punishment: A critical review. Religion, Brain and Behavior, 1, 46–99.

Shariff, A. F., & Norenzayan, A. (2007). God Is Watching You: Priming God Concepts Increases Prosocial Behavior in an Anonymous Economic Game. Psychological Science, 18, 803–809.

Shariff, A. F., & Norenzayan, A. (2011). Mean Gods make good people: Different views of God predict cheating behavior. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 21, 85–96.

Shariff, A. F., Norenzayan, A., & Henrich, J. (2009). The birth of high Gods: How the cultural evolution of supernatural policing agents influenced the emergence of complex, cooperative human societies, paving the way for civilization. In M. Schaller, A. Norenzayan, S. Heine, T. Yamagishi, & T. Kameda (Eds.), Evolution, culture and the human mind. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Shariff A.F., Rhemtulla M. (2012). Divergent Effects of Beliefs in Heaven and Hell on National Crime Rates. Plos One 7.

Sosis, R. and Bressler, E. R. (2003). Cooperation and commune longevity: A test of the costly signaling theory of religion. Cross-Cultural Research, 37: 211-239.