Segerfeldt collected a wealth of evidence about the improved efficiency and increased water access, particularly for the poor, after privatization in developing countries. Child mortality dropped due to improved water quality. Yet privatization sometimes involved price hikes because public utilities of water supply struggle to cover costs, limiting investment in infrastructure and expansion, leaving many without access to safe water. Indeed, political corruption is common and water pricing is often too low due to heavy subsidies, both of which lead to inefficiencies in supply and distribution. The performance of privatization was also limited due to regulations, such as the abolishment of currency parity and perverse pricing system in Buenos Aires, such as ownership limit in the Philippines. The highlight is that privatization can only work without those binding regulations.

Below, I highlighted the important passages in bold.

Water for Sale: How Business and the Market Can Resolve the World’s Water Crisis

Fredrik Segerfeldt, 2005.

Originally published as Vatten till salu : Hur företag och marknad kan lösa världens vattenkris, copyright ©2003 Timbro, Stockholm.

CONTENT [Jump links below]

Chapter 3: Shortage of Good Policies, Not of Water

Chapter 4: Water Rights — The Solution to Many Problems

Chapter 5: Markets and Conflicts

Chapter 6: The Price of Water

Chapter 7: The Possibilities of Privatization

Cambodia

Guinea

Gabon

Casablanca

More Examples

Chapter 8: Hazards of Privatization

Cochabamba

Buenos Aires

Manila

South AfricaCHAPTER THREE

Shortage of Good Policies, Not of Water

Weaknesses of Water Bureaucracies

The politicization of water distribution and the corruption this entails are no less problematic. When politicians have complete control of where, when, and how water is to be produced and distributed, this entails any number of risks. First, major infrastructure projects are undertaken for political rather than economic reasons, in which case, more often than not, they go wrong. [...]

Another problem is that water is usually handled by state-owned enterprises that are used to channel assets to the politicians themselves and their supporters. Researchers have shown that corruption is common in large public water projects, and in the Third World the interests of water producers are often put before those of the urban poor. Corruption also occurs on a lesser scale, in the form of employees selling water on the side (e.g., by charging customers to turn a blind eye to illegal mains connections), tampering with users’ bills, or allowing people to cut in line for mains water supply.

Politicians are above all anxious to please the constituents and groups on whom they depend for their reelection. Often these people are not the ones most in need of water, but advantaged groups like urban middle classes and well-organized big farmers. It can even happen that politicians deliberately retain systems that are economically inefficient but politically useful, because of the power that politicians and bureaucrats derive from them. This is the case, for example, when the price of water is kept down in order to raise demand. Politicians can then use quotas or other instruments to ensure that the water goes where it will do them, not the nation, the most good. Not surprisingly, quotas are also the most common way of regulating water demand in the least developed countries (LDCs). Landowners as a group often benefit greatly from low water prices, because when the price of water goes down, farmland prices go up. In this way, politicians can both butter up the big farmers and keep them to heel.

… For example, water is often steered, by means of quotas and subsidies, into agriculture, which is then able to produce more water-intensive crops than necessary, while industries that could make a bigger return on the same amount of water either have to go without or else have to pay more for it. André de Moor has estimated public subsidies to irrigation in developing countries to be between $20 and $25 billion annually. 42 Economic efficiency is then distorted, and the country as a whole is made poorer than it otherwise would be.

One aspect of water policy that is frequently overlooked is the lack of free trade in agricultural produce. This kind of trade could be thought of as trade in virtual water. Water is the most important input commodity for agricultural produce, so when buying produce from another country one is above all consuming that country’s water. There are extensive trade barriers where agricultural produce is concerned, and many countries apply a policy of self-sufficiency in foodstuffs. As a result, many agricultural products are grown in places where conditions for growing them are less favorable than elsewhere, and so agriculture consumes an unnecessarily large amount of water. Freer trade in agricultural produce, then, would reduce water consumption worldwide.

CHAPTER FOUR

Water Rights — The Solution to Many Problems

Perhaps the dilemma of the common is not such a dangerous problem in the case of, say, a Stockholm park, but things get more serious if the same argument is applied to a vital resource like water. In parts of California’s Mojave Desert, for example, water rights are linked to land ownership. Many landowners extract water from the same aquifer. Because water rights have not been regulated among the landowners themselves, many of them are extracting water in such quantities that the supply is dwindling. From the point of view of the individual landowner, it is of course rational to bag as much water as possible before the supply runs out. This could be termed ‘‘the tragedy of the common water.’’ Lack of property rights, in other words, causes overexploitation. The solution to this problem is private water ownership. Technically the true substance of ownership can be hard to pin down, at least where water flowing in a watercourse is concerned. There are various ways of overcoming this problem, but that is too technical an issue for our present purpose. 45

Chile introduced private ownership of water, with very good results. At the beginning of the 1980s the Chilean government granted farmers, companies, and local authorities the right to own local water. This enabled them to sell it in a free market, and the effects have been outstanding. Water supply has grown faster than in any other country. Thirty years ago only 27 percent of Chileans in rural areas and 63 percent in urban communities had steady access to safe water. Today’s figures are 94 and 99 percent respectively — the highest for all the world’s medium-income nations. 46 The Chilean success story can be attributed to several factors, such as prices matching the true cost of water and positive economic development in general. 47 But the most important reform was the introduction of the right to own water and to buy and sell it at freely determined prices.

Trade in water increased people’s access to water in two ways:

• The amount of water available increased, because the owners (farmers) now had a strong incentive to avoid spillage and produce and deliver as much as possible. The more they sold, the more money they made.

• The price of water fell, because the introduction of water rights led to a far-reaching decentralization of water management, thereby improving efficiency and reducing waste. In addition, the growth of supply put downward pressure on prices.

Farmers can often save water by using more efficient techniques of irrigation. Drip irrigation, for example, is more efficient than the traditional method. Only half the water used by the world’s farmers generates any food. Most of Chile’s new fruit farmers use water-saving irrigation techniques. Farmers can also switch to crops requiring less water. There is huge room for improvement here.

But farmers were not alone in husbanding water resources more carefully. When EMOS, Chile’s largest water utility (publicly owned at the time but since privatized), realized that it could no longer get water free of charge but would have to buy it from the owners, it invested in a program for heavily reducing wastage.

… It is quite common in poor countries for big farmers with good water supplies to grow water-intensive crops instead of those needing less water. In the latter case they could sell the surplus, for example, to industry. But you can’t sell what doesn’t belong to you. [...]

Chilean agriculture has accomplished a massive transformation, thanks to the trade in water. Most important, it has moved from low-value activities, such as cattle-farming and cultivation of cereals and oleaginous plants to fruit and wine production, which is much more lucrative. Between 1975 and 1990, without any major infrastructure investments being made, Chile raised its agricultural productivity by 6 percent annually, and today it is the world’s largest exporter of winter fruit to the Northern Hemisphere. 48

Water that is sold to a city instead of to another farmer will be used either by industry or by private individuals. Both cases mean good business for the farmer. Industry produces more value for the same water input, and private persons are ready to pay more for the water than the farmer can earn from crops. Either way, the price will be adjusted in such a way that the water goes where it will do the most good. The net gains of trading in rights can equal, or be several times greater than, the value of the rights themselves. 491

Trade also benefits urban dwellers. The Chilean city of La Serena, for example, has for years now been able to keep up with rising demand by purchasing water from farmers in outlying areas far more cheaply than if the city’s taxpayers had been forced to finance the dam construction project originally planned. [...]

Pakistan is another example. A survey by the Pakistani Water and Power Development Authority revealed water trading in 70 percent of the watercourses investigated. In places where the trade had been legalized, farmers’ incomes had risen by 40 percent. 50

As a third example we can take the Crocodile River in Mpumalanga, South Africa, where, historically, political control of water resources has had severe social, economic, and environmental consequences. But during a heavy drought in the early 1990s, the farmers began trading illegally in their water rights. Events showed that they were ready to pay up to three times the price officially set by the government. In this way, the water ended up where it did the most good and was used more efficiently. Much of the water shortage was remedied as a result. The authorities, perceiving the benefits of the water trade, eventually legalized it. Not only did this trade help farmers to weather a severe drought, it was also a stroke of fortune in purely economic terms. The net profit on the water trade is estimated at 25 million South African rands. As another positive effect of the water trade, plans could be shelved for building a great dam that would otherwise have cost 230 million rands of taxpayers’ money. 51

CHAPTER FIVE

Markets and Conflicts

Let us illustrate with the city of Warangal in the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh. Warangal has a problem with people stealing water from the canal that is its main source of water supply. Farmers quite simply divert water from the canal to enormous areas beyond surveillance. As a result the city’s water supply is constantly threatened, and the local authorities constantly have to negotiate with central authorities for a bigger allocation from the dam that feeds the canal. The city also builds small dams of sandbags, which are then removed by people dependent on the water downstream.

The farmers really have no choice but to steal water. The politically determined allocation is insufficient for their needs, and they have no possibility of buying water, because there is no such thing as a water market. But in other parts of India the appearance of tradable water rights has made water legally procurable. Added to which the water trade has led to more efficient use and, consequently, less shortage, which in turn reduces tensions and the likelihood of conflict.

CHAPTER SIX

The Price of Water

The big problem regarding the price of water in poor parts of the world is that it is too low for supply and demand to converge. Instead of water being made to bear its own costs, the production and distribution of it are subsidized out of taxation revenue. 64 No less than $45 billion a year is spent on subsidizing water in the Third World. In developing countries, the price of water is so low that on average it covers only about 30 percent of the water supplier’s expenses. Some experts estimate that the water sector is subsidized by an average of about 80 percent of expenses. 65

If not even current expenditure or working expenses are covered, there will be even less money to spare for maintenance and infrastructure investments to improve the distribution or quality of the water, and the supply network cannot possibly be enlarged in order to serve those who at present are without safe water.

Equally important, perhaps, is the determination of the water distributor to reach as many users as possible. If the price of water is so low that extending the supply network to new users costs more than the distributor can expect to recoup by means of charges, there is very little reason indeed why the distributor should want to enlarge the network at all, still less make the extra effort required in making such connections. Why invest in a guaranteed loss-maker?

… At the People’s World Water Forum that took place in Mumbai, India, in January 2004, Prakash Amatya, a Nepalese NGO worker, complained that ‘‘[t]he water shortage in Kathmandu is because water is almost free.’’ 66

But supply is not the only thing affected by price controls. If the price of water is politically set below the market price, demand will also become excessive, with a number of unfortunate consequences.

First, water will be wasted. Users have fewer incentives for economizing or limiting their use of water if it is too cheap. In the home, for example, no one stops to consider whether to use the same water for two loads of wash or whether more than one child can use the same bath water. The big savings, though, are to be made in agriculture, a point we shall be revisiting. Wastage helps to cause both water shortage and environmental destruction. The problem of waste becomes graver still when instead of water being quantitatively priced, the user pays a fixed charge. That completely eliminates any incentives for economizing.

South Korea offers a blatant example of water wastage. In 2002, when the country was experiencing a shortage of water, it emerged that South Koreans use more water per capita than any other OECD nation, despite their income level being one of the lowest. Water was heavily subsidized, and so wasting it cost very little. Compounding the complexities and vagaries of water management, the water bureaucracy numbered no less than five different public authorities. 67 […]

Industrial and agricultural use of water is even more important than domestic consumption. Between them, industry and agriculture account for 92 percent of world water consumption, and so this is where the big savings are to be made. 69 But they have little incentive for reducing their consumption when water is underpriced.

Farmers, who account for 70 percent of the world’s water consumption, are often hugely uneconomical about it. 70 For example, in growing water-intensive crops they derive a less-than-optimal nutrition content from a given quantity of water. Agriculture, in fact, is one of the real villains of the global water drama. The less developed a country is, the larger the proportion of its water is consumed by agriculture. So more efficient water use in agriculture will have the greatest effect in poor countries.

Half the water used by the world’s farmers generates no food. Minor changes, therefore, can result in much water being saved. A 10 percent improvement in the distribution of water to agriculture would double the world’s potable water supply. Here is another example: Tomato growing by traditional irrigation requires 40 percent more water than with drip irrigation. The water needed to grow rice on one hectare of land would keep 100 rural households supplied for four years. 71 If water costs what it is really worth, instead of being subsidized, farmers are very likely to make investments aimed at reducing the amount of water needed for food production.

One very clear example of the perverse effects of mistaken water pricing comes from California. Heavy subsidies give farmers a copious supply of water at very low prices. Urban dwellers pay nearly a thousand times as much for their water as farmers do. And so rice is grown in the desert, a water-guzzling enterprise, at the same time that Californian cities are spending huge sums of money on desalination plants converting sea water into fresh water. 72 […]

… Placing water distribution in private hands does not necessarily mean the price will be determined by the market. There is nothing to stop politicians from still controlling the price of water supplied under private auspices. … Instead, prices are most often determined politically, even after commercial interests have become involved. The most common arrangement is for the price to be inscribed in the contract drawn up between the public authority and the private player when the latter is admitted to the business of water distribution. [...]

The most common way for poor city-dwellers in developing countries to obtain water is by purchasing it from small-time vendors in kiosks, or those who either have a local well (with often polluted water) or deliver water by motor vehicle or by some other means. Contractors often drive tankers to poor districts, selling water by the can, in which case the very poorest of the world’s inhabitants are already exposed to market forces but on very unfair terms, because water obtained like this is on average twelve times more expensive than water from regular water mains, and often still more expensive than that. 74 (See table 6.1.) This is a very important point that tends to be completely ignored by anti-privatization activists. […]

For example, in Port-au-Prince, the capital of Haiti, people with mains water supply pay $1 per m3, whereas those lacking a main water connection pay $10 for the same amount. So the poor of Port-au-Prince would benefit from a price rise, even if water were made as much as nine times more expensive. 75 The same goes for most other Third World cities. In Vientiane, Laos, informal vendor water costs 136 times more than network water; in Ulan Bator, Mongolia, it costs 35 times more; and in Bandung, Indonesia, as much as 489 times more. 76 Unserved populations in these cities all stand to benefit from higher prices for mains water.

There are also survey reports showing that poor people in the developing countries are ready to pay more for their water than they are paying at present. 772 Other surveys show that price elasticity, that is, the sensitivity of consumption to rising prices, is lower in households than in agriculture and industry. 783 This, it might be argued, is only natural, since the consequences of being without water are direr for people than for farmers and industry. But on the other hand this confirms the possibility of conserving water by means of higher prices, since, as we saw earlier, agriculture and industry account for 92 percent of the world’s water consumption.

There are good examples of cities where higher prices have had very salutary effects. In Bogor, Indonesia, prices were substantially raised and the utility was able to connect more households to the main supply network, giving a greater number of poor people access to cheaper water. In Tegucigalpa, the capital of Honduras, groups of poor precincts joined force and signed an agreement with the water utility whereby the consumers themselves were to pay for the mains connection. Eighty-five percent of all households bought the connection and in this way had water brought to their homes, at the same time reducing their expenditure on water. 79

Another aspect to bear in mind when discussing the price of water from the viewpoint of the poor is the costs they already incur by not having access to piped water. As we saw in chapter 2, hundreds of millions of people spend several hours a day fetching water. During that time they can neither work nor study, and so they lose earnings. These losses are hard to quantify, but it would seem to be a reasonable supposition that several hours of unpaid, low-productive work a day means heavy losses, both to the individuals themselves and to the community as a whole. [...]

… Public water utilities cover only 30 percent of their costs. The remaining 70 percent is made up with subsidies from taxation revenue. Those who at present do not have access to any mains supply network are not reached by any subsidies either. In certain developing countries, between 80 and 90 percent of the wealthiest fifth of the population have access to publicly distributed water, as against only 30 to 50 percent or less of the poorest fifth. In Colombia, for example, 80 percent of all beneficiaries of water subsidies are people in medium and high income brackets. A study of six Central American cities showed that it was mainly the wealthiest 60 percent who were reached by subsidies. 814 In practice, then, it is mainly the well-to-do, such as the middle class and farmers, who benefit. [...]

In Chile, however, water subsidies have targeted the very poorest. Because water is self-financing, the majority of people pay the true cost of it, while extremely poor people are given a reduced rate. South Africa has a different system, but based on a similar principle, namely that of giving the poorest citizens access to water without encouraging overconsumption. All families are entitled to 25 liters of water daily, free of charge, while volumes in excess of that amount are a good deal more expensive. 83 But the South African model entails two problems. First, subsidies benefit everyone, not just the poor; and second, water utilities have little incentive for extending the water supply system to poor people who are not expected to consume much.

… Subsidies are expenditure that the state finances out of taxation revenue contributed by the population. Those who benefit from subsidized water, then, are to a great extent the people who also pay for the benefit, albeit indirectly. The only people who pay for the subsidies without deriving any benefit from them are in fact the very poorest, who do not have access to mains water.

Chile’s former secretary for agriculture, Renato Gazmuri, points out that the former Chilean system of state-subsidized water actually implied a regressive redistribution of wealth. Since low-income earners consume a larger portion of their income than the well-to-do, a larger part of their income goes to taxes (consumption being taxed more heavily than savings and investments). And since low-income earners consume less water and thus obtain a smaller share of the subsidies, water subsidies in practice imply a transfer of resources from the poor to the better-off. The middle class gets cheap water and the poor foot the bill. 84

Andrew Nickson, who has written a report on the subject for the UK Department for International Development (DFID), aptly summarizes the whole matter as follows:

The publicly-operated water sector in low and middle-income countries is failing to meet the needs of the urban poor. Instead it has ended up subsidizing the convenience interests of the rich. 85

The cost of subsidies directed at the Chilean poor amounts to $40 million. The general subsidies were costing no less than $100 million, that is, more than twice as much. [...]

Another way of helping underprivileged households when subsidies vanish is by distributing water vouchers that entitle them to a certain level of water consumption and for which the water utility then invoices the state. Where feasible, this is probably the best way of guaranteeing that poor households can afford the basic amount of necessary water, while at the same time making sure that the operators get the capital and incentive to reach the poor with their networks. [...]

One reason for expecting prices to rise is that any public subsidies will disappear once commercial interests are admitted. It would be quite possible to go on subsidizing water distribution by transferring funds to the private firm, but usually this does not happen, because one reason for governments transferring water distribution to private enterprises is that they are short of resources and want to cut costs and use public funds for different purposes. [...]

… Nor is it certain that investments will lead to higher prices in the slightly longer term. Let us consider an example from another industry. When Volvo invests millions in a new car model, it counts on getting its money back. The new model is attractive in the eyes of customers, and so it sells well. A new production line is more efficient than the old one, enabling cars to be sold for less. The customers get a car that appeals to them, and more people can afford it. Thanks to the growth of efficiency, the employees working on the new production line are more productive and can therefore be paid more (perhaps they have also undergone some kind of training), which in turn stimulates the economy around them. The public sector pulls in more taxation revenue from the company’s profits and the employees’ earnings and also from the purchases made by the new car owners. In short, everyone benefits.

Or consider an even clearer and perhaps more immediate example from the pharmaceutical industry. After investing heavily, a company invents a new drug that will enable thousands of people to recover their health and return to work, becoming a source of income instead of an item of expenditure to the public sector.

The same goes for water. In the longer term, investments lead to a growth of earnings and a fall in expenditure. Private enterprise reaches more users with fewer employees and at lower cost.

CHAPTER SEVEN

The Possibilities of Privatization

Opponents of private involvement in poor countries tend to put a privatization label on all forms of entrepreneurial involvement in water distribution. … In fact, there are very few systems in the world today with completely privatized water assets and completely deregulated suppliers. Only a tiny proportion of the private investments made in the water sector in developing countries represent outright privatization. Most often they represent various forms of cooperation between public- and private-sector or government and business. These connections are frequently labeled water privatization. 86

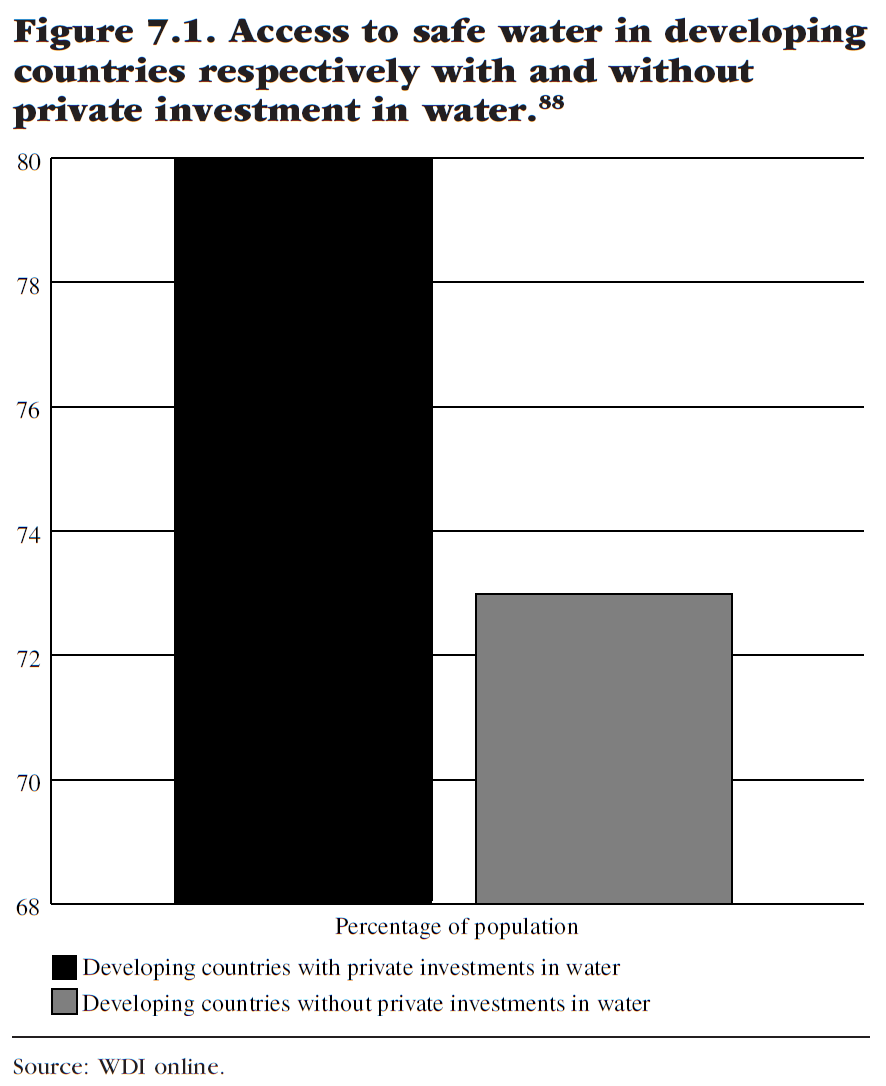

… Third, companies have perceived that water sales to the poor can be an important part of the market that they simply cannot afford to disregard. The poor, then, have great commercial value as consumers. Often they make up no less than 50 percent of a country’s total market and thus cannot be ignored, politically or economically. So the challenge of supplying the poorest citizens with water is an integral part of corporate business planning. And, as shown in figure 7.1, companies have succeeded quite well in this respect.

… The greater the involvement of the private sector in water supply, the greater the number of people with access to water. 875 [...]

The superior results achieved by private water distributors are also confirmed by a long line of studies, mostly of distributors in the industrialized world. The World Bank, though, has made a larger comparison between 50 water distributors in developing countries of Asia and the Pacific, showing private firms to be more efficient. 906

Cambodia

Cambodia, like most other developing countries, has water distribution problems. 917 … In three provincial cities, a private company was licensed to distribute water for three years. In a fourth city, no public resources were transferred. Instead, a private concern was granted permission to build a water supply network of its own in those outlying city districts that were not already served by the public water supply network. In the other 19 provincial cities, water distribution was entirely under public management.

Unfortunately, procurement in the first three cities was conducted without transparency, which left room for corruption and trade restraint, added to which the contracts were unclear as to what was required of the companies and on what terms their contracts would be renewable. Even so, the companies invested large sums of money in improving the water distribution system.

Cambodian politicians were of various minds as to whether the admission of commercial interests was a good or a bad thing, and so a survey was carried out, comparing water supply in the four cities with private involvement with that in four other cities where the supply remained public. The findings were unambiguous. Distribution worked better in the cities where commercial interests had been admitted.

Households in the cities with private water distribution were far more satisfied with the distributors’ service than those in cities with public water utilities. Availability was better, in the sense of there being water in the faucets more often. All but one of the towns with private distribution had water on tap 24 hours a day. In cities with public distribution, water was available for between 8 and 12 hours a day. Cities with private water systems also had fewer disruptions of supply and better-quality water.

There were several reasons for the superiority of the private distributors. First, they had better-qualified, better-paid personnel. Second, their network maintenance was more regular, and they introduced programs for carefully monitoring the quality of the water. Last but not least, the private distributors were more strongly motivated to pursue customer satisfaction. So the strong points of private water distributors in Cambodia were very much an inversion of the weaknesses of public water utilities in developing countries: corporate management, quality-awareness, and incentives for uninterruptedly supplying good-quality water to as many people as possible.

True, the price of water was somewhat higher in cities with private water, but the difference was barely 6 percent. This slight difference was more than offset by the benefit of a regular domestic supply of safe water. What is more, the private distributors issued receipts for the greater part of their earnings, which leads one to suspect that the public utilities had a certain amount of income that went unreported, and that the real price of the water supplied by them was higher than officially stated.

Guinea

Guinea offers one of the earliest and most widely noticed instances of a poor country admitting private interests to its water sector. 92 In 1989, when water management in the cities was handed over to a private company, little more than two Guinean urban dwellers in 10 had access to clean, safe water. Twelve years later, in 2001, the figure was no fewer than seven in 10 (see figure 7.2). The welfare benefit from privatization has been estimated at no less than $23 million. 93

It is astonishing that the number of people with access to clean, safe water should have risen so dramatically in little more than a decade. Changes of this kind have been seen in countries developing very rapidly, but this is not the case with Guinea, which is a very poor country. Much of its economic growth has been eaten up by a growing population and servicing of the national debt. Instead the remarkable improvement can be put down to the private company, unlike Guinea’s government and civil service, having the capital, competence, and incentive to deliver clean, safe water to as many people as possible. [...]

Guinea is well off for water. It is estimated to have 166 billion m3 renewable water, although many of its water sources are shared with other countries. But the end of the 1980s found its national water supply in complete disarray. As illustrated in figure 7.2, only 23 percent of the urban population had access to clean, safe water. Only 10 of the country’s three cities had water mains. In Conakry, the capital, the situation was critical. The population was increasing rapidly, and people’s needs could not be met by the public distributor.

According to Ménard and Clarke, ‘‘Despite substantial loans from international donors, coverage was low and many non-connected residents drank water from polluted wells. Because of this, water-borne diseases were the main cause of death of infants and children and there were periodic cholera epidemics. The public enterprise responsible for the sector, the Entreprise National de Distribution de l’Eau Guinéenne (DEG), was poorly managed, overstaffed and practically insolvent.’’ 94 It was able to produce only about 25 m3 per inhabitant annually. There were only 12,000 connections (end-user pipes) in the whole country, and of these only 5 percent were fitted with meters (see table 7.1).

The reasons for this situation, once again, were lack of resources and administrative ineptitude. Guinea’s bureaucratic weaknesses were perhaps even more conspicuous than Cambodia’s. The allocation of responsibilities among various authorities was unclear, water management was fragmented, and civil service efficiency was very poor.

In 1989, a public–private partnership (PPP), 95 funded with credits supported and underwritten by the World Bank, was formed by a national water utility and a private water company. The national utility, which has greater autonomy and flexibility than the civil service, is tasked with planning, running, and owning the water infrastructure. This is then leased to the private company, which collects payment from users in the form of connection and consumption charges.

It must be said that this PPP has not run altogether smoothly and that not all the project targets have been achieved. But there have been dramatic improvements. Delays and cost overruns on various construction projects were substantially reduced. The water supply network has been extended to more cities, and the number of connections has risen steeply. The proportion of urban dwellers with access to clean, safe water has nearly tripled, and Conakry’s water production has doubled.

Everyone in Conakry seems to agree also that the quality of the water was superior after privatization — the general public, the World Health Organization, and local consumer organizations, as well as the manager of the local Coca-Cola plant (who should have quite deep knowledge of the matter). The effect, then, has been quite the opposite of that alleged by the detractors of commercial-interest involvement. 96 […]

Privatization in Guinea boosted efficiency tremendously. The fact of 95 percent of all end-user pipes now having meters enables the company to collect payment for the water supplied. In this way the company earns money and can pay the rent for the infrastructure to the government, which in turn can use the rent money for investments in infrastructure, both new and old. More and more people gain better and better access to clean, safe water.

The question of water pricing is bound up with incentives. The price paid for water in Guinea, by the few people connected to the public water mains, was heavily subsidized. In other words, it was so low that the proceeds from water sales did not cover costs. And so the system was badly run, the existing infrastructure was poorly maintained, and there was a shortage of investment capital for reaching more users. Since the investment, the price of water has gone up quite a lot, from 15 cents per m3 in 1989 to almost a dollar in 2000. To offset these price rises, a sliding-scale subsidization scheme was introduced, which was phased out in 1995.

The most important point in the pricing discussion, however, is that before privatization the majority of Guineans had no access to mains water at all. They do now. And for these people, the cost of water has fallen drastically. The moral issue, then, is whether it was worth raising the price for the minority of people already connected before privatization in order to reach the 70 percent connected today. Given the dreadful consequences of being without clean, safe water, this question can only be answered in the affirmative. 97

Gabon

Some opponents of private involvement in water supply in poor countries concede that it may have had positive effects in a few Third World cities. But, it is argued, the majority of people in poor countries who are short of water live in rural areas, where urban logic does not apply. Distances are far greater than in the towns and cities, and lack of infrastructure in the form of roads and other public works would make the enlargement of the water supply network a very expensive business. Costs being so high, it would be hard for private companies to achieve profitability without raising prices beyond what poor people could afford. Privatization, then, is no panacea for water shortage in developing countries.

This objection does not hold, for several reasons. In the first place, 48 percent of the earth’s population live in urban communities, and by 2030 this will have risen to 60 percent. Most of the additional 3 billion people born over the next 50 years will be urban dwellers, as will two-thirds of the people that need to be connected to a water network to reach the Millennium Development Goals. 98 William Finnegan, in a New Yorker article, puts it neatly:

This enormous slow-motion public-health emergency is, in large measure, a result of rapid, chaotic urbanization in the nations of the Global South. 99

Furthermore, UN-Habitat has shown that the seriousness of the problem in urban areas seems to have been underestimated, and that the lack of water and sanitation causes more serious harm in cities than in rural areas. For example, a water source a few hundred meters away from a household in an urban setting can mean hours of waiting in line, whereas in rural areas this can be a relatively convenient solution. Also, defecation in the open is obviously less hazardous where there is plenty of space. 100

Last but not least, there are good examples of private investments with successful outcomes in rural areas too. One of these comes from Gabon, where in 1997 the government signed a contract with a French company to take over the distribution of both water and electricity nationwide. 1018 The contract defined targets for the percentage of the population to be reached by the national grid and the water supply network and stipulated that prices were to be reduced by 17.25 percent. At the time of privatization the public utility was delivering water to 32 communities, but large parts of the countryside had neither electricity nor mains water.

The privatization has been a great success. In only five years, the company made 40 percent of the investment the contract stipulated for a period of 20 years. These investments have had the effect of raising water quality and lowering prices. The private distributor has also achieved all the network enlargement targets defined, and in some cases exceeded them. Fourteen percent more households than previously now have access to the water supply network. 1029

… Among other things, as private operators have done in numerous cases, it has devised innovative methods for delivering water to households at very low cost. 103 The most convincing proof of how well water distribution is working today compared with its public-sector days is people’s opinions. Customers, that is, the population of Gabon, are more satisfied with water distribution today than when it was operated as a public utility.

Casablanca

Centralization is one of the great problems besetting water supply in poor countries. Local players and representatives are far removed from power over water, which is wielded by politicians and bureaucrats in the capital cities, often in close collaboration with aid donors and producer interests. These, in turn, are remote from the users and have little incentive for making improvements. After all, they themselves are not directly affected. … We saw the positive effects of decentralized ownership in the Chilean example described earlier. But decentralized power can also yield positive results. The closer the decisionmakers are to the users, the more incentive they will have for improving distribution. Casablanca, Morocco, is a case in point. 104

Demand for clean water in Morocco rose steeply at the beginning of the 1980s, partly because the urban population grew from 8.7 million in 1982 to 13.4 million in 1994. Meeting this added demand would call for investments — investments that the government, with its limited resources, had neither the capital nor the competence to make. So the government opted for a strategy comprising a number of measures. Two of them were the decentralization of power over water management and the admission of private interests. The cities, quite simply, were given a freer hand in deciding how to tackle the problem.

During the 1990s, a number of cities decided to invite private interests. Casablanca, the largest city in Morocco, formed a PPP that entered into force in 1997. A contract was signed with a private consortium consisting of a number of international and local players.

This private concern invested the equivalent of about $250 million between 1997 and 2002, inclusive. This, coupled with the firm’s modern technology and management capacity, led to a whole string of improvements. Greater efficiency and reduced spillage enabled the company to supply growing numbers of customers with more water, even though it was producing less. The quality of the water improved. In addition, the company improved the management of effluent, even though this was not included in the contract.

The company has cut down on personnel strength. But on the other hand, more employees are undergoing further training today than when water distribution was a public operation, and personnel mobility within the enterprise is far higher than it used to be, with the result that more employees are landing in positions where both they and their employer are satisfied with their jobs. Wages have risen and are now decided more by the competence and performance of the individual employee. Health and safety conditions have improved, and an information technology system has been installed.

Furthermore, response to the users, who are treated like customers by the company, has improved immensely. Consumption is being metered more efficiently, distribution is far more dependable, complaints are fielded in a positive spirit, and faults are dealt with more quickly than they used to be. The local authorities, for their part, no longer have to devote a large proportion of public funds to water distribution but can instead make the social investments on which the cities of Morocco so strongly depend.

More Examples

Other examples can be quoted of water distribution in poor countries benefiting from decentralization. A study comparing water distribution in Senegal and the Ivory Coast arrived at the conclusion that, although conditions were similar in both countries, water distribution worked better in Senegal. Greater decentralization and local influence in that country can help to explain the difference. 105

In addition to figures at the macro level and the cases we have nowreviewed, there are a number of studies comparing water supply network coverage before and after privatization in various Third World cities. A trawl through a number of studies by the World Bank showed privatization to have increased people’s access to water in all the cases investigated. 106 In addition to the cities and countries that have already been mentioned in this book, the review covered three cities in Colombia and one in Argentina as well as the increase resulting from privatization there. (See figure 7.3.)

Privatization and commercial involvement in water distribution also have a positive environmental impact. There are eloquent examples of public water–infrastructure ventures with very adverse environmental consequences. Political regulation of water pricing and supply has also had disastrous effects. In Pakistan, for example, low prices have led to overconsumption, causing sensitive mangrove swamps to disappear and biodiversity to diminish. 107 It is common knowledge, from statistics and case studies alike, that privatization of public utilities generally has a favorable impact on the environment. 108 Private businesses bring with them new capital, new techniques, and management skills. Their pursuit of competitiveness leads them to use resources efficiently. This includes the water sector. […]

As regards the protection of water as a natural resource, things are not looking good in the world today. For example, 20 percent of all freshwater fish species are endangered or have recently been exterminated. The worst situation of all prevails in the developing countries. In the Nile Delta, 30 out of 47 commercial fish species have been exterminated and a fishing industry that once employed a million people has been obliterated. On average in the developing countries, between 90 and 95 percent of all domestic wastewater and 75 percent of all industrial waste is discharged straight into the surface water, without any purification whatsoever. New Delhi discharges 200 million liters of raw sewage and 20 million liters of industrial effluent daily into the River Yamuna, which flows through the city on its way to the Ganges. 109

Western companies, with the competence and capital to manage water and sanitation in keeping with quite different environmental stipulations from those generally prevailing in developing countries, will help to protect the Third World’s water. Aguas Argentinas is a good example of this. This company’s superior efficiency enabled it to reduce input of water purification chemicals compared with the situation when water distribution was publicly controlled. Commercial forces have made the company keep a closer watch on water quality, improve its water purification, reach more users, and extend the sewerage network in order to reduce the quantity of raw sewage discharged into the environment. 110

… In arid regions, environmental impact is less in countries with recognized trading in water rights than in countries without such trading. 11110 Formally recognized property rights also make it easier to control the management of water. If no one is responsible for water, there will be no one to regulate its use. Privatization has also induced governments to tighten up legislation and to keep a closer check on compliance with environmental laws and regulations. Of course, it is easier for a government to press charges against a private enterprise than to take itself to court for violations of its own environmental regulations. And having the threat of legal action hanging over one’s shoulder is an important incentive for a supplier to follow regulations.

Privatization protesters usually argue that privatization will harm the environment, not help it. But it seems very hard for them to find evidence of this. Instead, they rely on anecdotes. For example, the Polaris Institute, in one of its pamphlets, mentions three examples of water companies being charged with violations of environmental regulations. 112 (Oddly, even though the focus of the document is poor people in the world, all three cases took place in Europe — not in developing countries.) True, mistakes are made by companies, individuals, and governments. We can always find examples of successes and failures, both private and public. That is the nature of human activity. The important thing, though, if we want to have a serious discussion about this issue, is the overall result at the global level. What tends to work, and what does not? And here, anti-privatization activists fail to present any evidence of private suppliers having a worse environmental record than public ones. In general they present neither data nor any analysis of the strengths and weaknesses of private distributors as opposed to public ones when it comes to the environment. Considering the record of public water suppliers, there are good reasons to believe that a full comparison would show the advantages of privatization.

CHAPTER EIGHT

Hazards of Privatization

Why is privatization, or any opening up to private enterprise, such a delicate issue where water is concerned? Many other sectors, such as power, telecommunications, and postal services, have in various ways been opened up to competition and/or privatized all over the world, generally with highly positive results in terms of quality, productivity, and profitability. 11411 The distribution of water, however, is considered different from other traditionally public activities, because access to water is literally a matter of life and death, even in the short term. [...]

Cochabamba

Water distribution in Cochabamba, the third-largest city of Bolivia, was privatized at the end of the 1990s. Aguas del Tunari, a subsidiary of an American corporation, was granted a 40-year lease on water distribution. This is the anti-globalists’ and anti-privatizationists’ favorite example.

The water distributed by the public utility was heavily subsidized, which meant that its price fell considerably short of the true cost of distribution. AdT, however, charged a higher price, corresponding to its expenses. The price of water charged to poor people rose by 43 percent, while that charged to the middle class and commercial users rose by just under 60 percent. Demonstrations and riots followed, and people were killed and injured in clashes with the forces of law and order. In April 2000 the contract with AdT was repudiated, and water is now once more being managed and distributed under public auspices.

This case is usually highlighted to evidence the negative consequences of privatizing public goods. Almost triumphantly, various activist groups and NGOs have blazoned forth this unfortunate example as proof of the disastrous consequences of admitting commercial interests to the water sector in poor countries. At the same time, they have cynically welcomed disturbances in which people have been killed or injured. 120

The contrast between a large American corporation’s operation and the access of poor Latin Americans to water abounds, of course, in pedagogic simplicity and dramatic media potential, but news media reporting from Cochabamba have not conveyed an accurate picture of the true causes of the failure and disturbances. 121

The first misapprehension concerns the price rises and the effect on ordinary people’s finances. The higher prices are alleged to have compelled many people to spend as much as a quarter of their available income on water. 122 This is not the case. A 43 percent price rise meant the cost of water equaled 1.6 percent of an average household’s income. For the poorest 5 percent of the population, the corresponding figure was 5.4 percent. Not even a doubling of the price of water would have resulted in any group on average having to spend as much as a quarter of its income on water. 12312 Most experts argue that poor households are expected to be able to spend as much as 5 percent of their income on water. Assuming this is correct, the 5.4 percent cost can hardly be seen as excessive, nor can it be the sole cause of social uproar.

Another reason why people found their water bills higher than usual is that before privatization water was rationed, the reason being that the water mains were in such poor condition that leakages did not leave enough water to go around. These leaks diminished after privatization, with the result that rationing was no longer necessary, which in turn caused consumption to rise and billings with it. The unit price of water had not gone up all that much, but consumption had.

Another aspect to be factored in here concerns the workings of Cochabamba’s water distribution before privatization. It was awful. For decades SEMAPA, the Bolivian public water utility, had failed to extend its network to the very poorest. Between 1989 and 1999, the proportion of households connected to the water supply network actually fell from 70 to 60 percent. 12413 Those who were connected often had their supply cut off. Water was heavily subsidized, which mainly benefited the upper and middle classes, and it was these people who experienced the biggest price rises. The poor paid far more for water of dubious purity from trucks and handcarts.

UN-Habitat describes the inadequacy and inequality of Cochabamba’s water distribution:

Industrial, commercial and wealthier residential areas have the highest rates of connection, reaching 99 percent in Casco Viejo. Yet half of the homes in Cochabamba are located in the northern and southern suburbs, and in some districts in these areas, 1992 data indicate that less than 4 percent of these homes had potable water connection. . . . There is insufficient water provision to meet existing levels of demand. 125

But the price rises are not the only thing to have been misrepresented. The blame to be pinned on the local authorities has been disregarded. The mayor of Cochabamba, Manfred Reyes Villa, known as Bonbon, had connections with companies that would profit from the construction of a dam, and he insisted, against the advice of the World Bank, that the dam be included in the project, which incurred an extra cost of millions of dollars.

Finnegan argues that some of the financial backers of the mayor ‘‘stood to profit fabulously from the Misicuni Dam’s construction. When the central government first tried to lease Cochabamba’s water system to foreign bidders, in 1997, and did not include Misicuni in the tender, Bonbon stopped it cold. It was only the inclusion of the project in the Aguas del Tunari contract that got the mayor on board.’’ 126

Another misapprehension has it that the political disturbances just came out of the blue. They did not. From the very outset, the position of Cochabamba’s political leadership was weak and challenged. As Finnegan points out, ‘‘The dam project had less to do with how privatization works in theory than with the reality of how multinational corporations must come to terms with local politics.’’ 127 The local political situation was a mess of patronage, populism, and vanity projects.

There are also murkier sides to the Cochabamba story. For one thing, the true victims of water privatization were powerful vested interests. Various groups that had previously been involved in the distribution of water (such as local water vendors and companies boring wells) felt threatened. Small farmers were tricked into believing, against their better judgment, that their traditional right to local water was threatened, even though a law had just been passed stipulating that this was not to happen. When SEMAPA officials could no longer be bribed to place wealthy households in a lower income class to qualify for a lower water rate, or when commercial customers could no longer be registered as households to the same end, suddenly these powerful groups found themselves with far higher water bills to pay. All these groups cynically exploited poor urban dwellers as an excuse for safeguarding their own interests.

It seems that the incidents in Cochabamba were part of a very complex story. Middle-class anarchist students, retired nostalgic unionized workers, forces with a vested interest in water remaining in public hands, and people who make up the large, informal economy of the city joined forces and used anti-capitalist and anti-foreign rhetoric against a primarily white government fearful of an uprising of the primarily Indian majority of the country.

Water distribution has been returned to SEMAPA. The poor of Cochabamba are still paying 10 times as much for their water as the rich, connected households and continue to indirectly subsidize the water consumption of more well-to-do sectors of the community. Water nowadays is available only four hours a day, and no new households have been connected to the supply network. 128

Jorge Quiroga, then president of Bolivia, said, ‘‘The net effect is that we have a city today with no resolution to the water problem. In the end, it will be necessary to bring in private investment to develop the water.’’ 129 The dispute between AdT and the Bolivian government has been brought to the World Bank’s International Center for Settlement of Investment Disputes, where the case is still pending as of February 2005.

The Cochabamba case is much more complicated than it has been made out to be, and cannot reasonably form the basis of any conclusions as to the pros and cons of water privatization. If anything, it is an object lesson in how not to privatize and in the corruption, powerful vested interests, and populism that beset Bolivia and other parts of Latin America.

Buenos Aires

Another case of privatization that has attracted considerable attention comes from Buenos Aires, the capital of Argentina. 130 The background is as follows.

In 1993, the production and distribution of water were transferred to a private company, Aguas Argentinas. Up until then, Buenos Aires’ water distribution had been a sorry business. The public utility, OSN, had grossly neglected its infrastructure investments. Progressively fewer people were being supplied with water, the pressure in the pipes was steadily declining, and in summer the supply often dried up completely. Little more than half the 5. 6 million people living in the poor districts of the city were connected to the water supply network, as against nearly all the 3 million living in the more affluent districts. Spillage was 45 percent, 99 percent of water consumption was not metered, and only 80 percent of bills were being paid.

Privatization changed things dramatically. Heavy investments and efficiency improvements radically boosted output. Potable water production in 1998 was 38 percent higher than it had been in 1992. The private distributor quickly reached a million more users than the public utility had, and within a few years the number of households connected had grown by no less than 3 million. 131 Thirty percent more households gained access to water pipes, 20 percent more to sanitation. … Most (85 percent) of the new customers were in the poor suburbs of Buenos Aires. They now gained access to water that was 10 times cheaper than the water they had previously been compelled to buy from small-time local vendors.

The price went down as well. In 1998, water cost 17 percent less than it had in 1992. Quality, which presented certain problems to begin with (mainly as a result of poor information concerning the state of the infrastructure under the public régime), was also appreciably higher in 1998 than it had been. Some of these improvements can be attributed to Aguas Argentinas raising money for investment and maintenance by actually collecting payment for the water. But the big change was the company’s superior competence and capital, its greater efficiency, and its clearer incentives.

When the water authority was privatized, personnel strength was approximately halved, from 8,000 to 4,000 employees. OSN was heavily overstaffed and had four times more employees per water connection than the Santiago distributor in neighboring Chile. Absenteeism was very high. The average age of the staff was 50. Most of the manpower reduction, therefore, was achieved through retirements. 132 Meanwhile, all the investments entailed by the privatization project have created between 4,000 and 5,000 job opportunities altogether. The welfare effects of privatization — meaning its benefits to the national economy — were already estimated in 1996 at no less than $1.5 billion, $1.3 billion of which stayed in the country. This is a conservative estimate, because the figures do not include health improvements, a matter to which we shall be returning presently. 133

Buenos Aires’ water privatization was part of a whole package of structural reforms introduced in Argentina in the 1990s. 134 Thirty of the country’s municipalities, comprising 60 percent of the national population, privatized their water distribution. Far more residents in municipalities with privatized water are now served by water mains than in municipalities that have not privatized. Not only have these privatizations led to people gaining better access to cheaper water of higher quality, they have also had important secondary effects, most important among them being a reduction in child mortality.

A large proportion of child deaths in Argentina, as in so many other developing countries, are from water-related causes, either water-borne diseases or lack of water for hygienic purposes. Diarrhea, septicemia, and gastrointestinal infections are closely connected with water. These three diseases are also included among the 10 common causes of death among children under five in Argentina. In municipalities that have privatized their water, between 5 and 7 percent fewer children are now dying from water-related causes, compared with municipalities where water is still supplied by public utilities. The effects were greater still in the poorest municipalities. Child mortality there dropped by a massive 24 percent. Water privatization in Argentina, in other words, has saved the lives of thousands of children, most of them poor. 13514

For all these good results, criticism of Buenos Aires’ privatization has been unsparing. There is talk of greed, betrayal, and broken promises. 136 First of all, opponents point to allegations of corruption in connection with privatization, and rightly so: the politicians were far too closely involved in the process. But private players do not have a monopoly on corruption, which is also rife among public water utilities. (Enhanced transparency and the introduction of full cost recovery reduce the scope for corruption of privatized water utilities. How privatizations are to be carried out will be further discussed later on in this chapter.)

The ‘‘greed’’ argument hardly merits rebuttal. Pursuit of profit is the driving force of private enterprise. Anyone is free to have an opinion about profit, even to the point of calling it greed, but that is how the market economy is constructed, and so accusations of greed belong not so much to a discussion of water privatization as to the discussion of the market economy qua system, which is beside the point for present purposes. Suffice it to say that systems founded on ‘‘greed’’ have given citizens much better lives than systems without any such foundation. It is worth adding, and repeating, that profit is what impels companies to satisfy as many customers as possible, in the present case people who need water. [...]

Another frequently cited consequence of privatization is that it often brings job cuts. Many opponents of privatization claim that prices will rise, but at the same time oppose any job cuts, which have the effect of reducing costs. They are against both these phenomena, regardless of their necessity. But you can’t have it both ways. With fewer employees, the company has more scope for price cuts. 137

The question, then, is whether staffing reductions are a good or a bad thing for an inefficient public operation. Does it make sense to refrain from privatizing an operation simply because the people employed by it then risk losing their jobs? If so, all the country’s taxpayers and water users will have to subsidize a number of people who are in the wrong place. Poor attendance and low productivity show that many people were not all that happy in their work with the Buenos Aires water authority before privatization. The fact of the enterprise being able to produce more water than before with only half the previous personnel strength shows that it was greatly overstaffed. Applying the resources to something more productive is preferable to bolstering jobs in the water sector. The fact that at least a few of the staff of OSN seem to have been unnecessary employees gives further strength to this argument.

Furthermore, the workers who remained with the company seem to be better off than before. They own 10 percent of the company, and are better educated and better paid. The company uses better technology and has more computers and more professional management. Whether these improvements are less important than the layoffs is hard to say, but it is obvious that the issue is not as clear-cut as the union would have it.

But privatization in Buenos Aires has not been painless. The fact is that the price of water has gone up and down in quite an arbitrary fashion. Mostly it has gone up, but price reductions have happened. In 1994, when the first price increase occurred, many users indignantly refused to pay.

In 1997 the company wanted to renegotiate its contract, as did the public authority, in order to tighten stipulations concerning Aguas Argentinas’ environmental performance. But the negotiations went badly, very much due to federal authorities dealing directly with AA, over the heads of ETOSS (the authority tasked with controlling AA). This resulted in prices to existing subscribers rising and those for new connections going down. Once again there was public discontent, with 51.9 percent of Buenos Aires’ residents opposed to water privatization, as against only 38.6 percent in 1988. 138

The need for new negotiations showed that the demands initially made were not realistic, and the company was also given to understand that it would come to little harm from not honoring its commitments.

In 1998 the price went up as contractually agreed, provoking something of a public outcry. The politicians on the ETOSS directorate were not able to agree on the prices that should be charged, because their different electoral followings had been unevenly affected by the price rises. The result was a highly fragmented debate, first between politicians and then in the press, causing discontent to spread to the general public even though water was still cheaper than it had been before privatization and many more people were now connected to the mains network.

In 2001 and 2002, Argentina went through the worst economic crisis in its history. When the government abolished the parity between the peso and the U.S. dollar, the peso nose-dived, and the government aimed to revise the regulatory and contractual framework applying to the privatized utilities. The company was no longer allowed to charge its customers pesos equivalent to value in dollars, since it would have tripled the prices. Aguas Argentinas thus saw its earnings — which were in pesos — fall dramatically in relation to its expenditures, which were largely in dollars. The company then wanted to raise the price of water to offset its exchange rate losses, but the national authorities would not agree to this. At the time of writing, February 2005, the company is still negotiating its contract with the authorities. An interim agreement is in place, but the Argentine government seems to be striving to gain full control over Aguas Argentinas, either by turning the company into a private-public partnership or by nationalizing it. Either way, it is clear that the government wants to define the rules of the company operations by itself. 13915

It is vital to observe here that there is nothing to suggest that a public distributor, which would also have been dependent on credits to make the huge investments needed, would have weathered Argentina’s crisis any better. A public utility would have faced the same problem, and would also have been constrained to negotiate big credits to finance the investments needed for improving the distribution of water. The only difference would have been the utility being forced to seek compensation for rising costs through taxation instead of raising the price of water. The same people, then, would still have had to cover the costs, but less evidently so, because the fact would have been cloaked in a tax hike. Once again it should be recalled that the winners under public water régimes with general public subsidies are not the poor — neither those who lack mains water connections nor those who pay the tax that finances the subsidies.

The privatization of water distribution in Buenos Aires cannot be termed a failure. Millions more residents have gained access to safe water and need no longer make do with expensive water that is dirty and contaminated. On the other hand, the operation has not been a complete success. Why did it not succeed better? Analyzing the situation, Lorena Alcázar, Manuel A. Abdala, and Mary M. Shirley have explained that the privatization was flawed in three basic respects: asymmetric information, the wrong incentives, and poorly controlled institutions. 140 They already foresaw in 2000 that these faults would result in the privatization being called into question.

Let us begin with the information aspect. First of all, the bidding process was characterized by lack of information. It took place before the authorities had time to supplement or rectify deficiencies and erroneous information. These shortcomings concerned, for example, the quality of the public utility’s infrastructure and finances. Some people in Argentina also claim that trade unions, which were opposed to privatization, destroyed records in order to make it more difficult for companies to evaluate the state of water distribution before bidding and, once in operation, to carry out the investments necessary to improve distribution.

In addition, Aguas Argentinas inherited an inefficient and impenetrable pricing system. Most users paid a fixed price based on the location, age, size, and type of their home, with any number of coefficients taken into account. This gave the enterprise a strong informational lead on both customers and authorities, enabling it to act opportunistically in relation to regulatory bodies and making it virtually impossible for customers to understand their water accounts and even more difficult to analyze price changes.

Moreover, ETOSS, the regulatory body, had a number of built-in weaknesses. It was supposed, among other things, to ensure that the company met its obligations under the concession contract and to impose fines if it failed to do so, as well as to receive, assess, and remedy customers’ complaints. But the agency was newly formed and had to learn the job as it went along, added to which most of its staff were former employees of the public water utility, with neither legal nor commercial skills. The enterprise also had the advantage of ETOSS in terms of information. This, coupled with the contract enabling the agency to interfere in the details of AA’s running of its business and make arbitrary stipulations, caused problems.

It was clear that the contract had made unrealistic demands from the outset. Aguas Argentinas therefore expected the terms to be amended. It was not alone in this, because the company that came second in the tendering process quoted only a marginally higher water price. As we were saying earlier, it is important for the enterprise to make money out of each new connection, so that it will be disposed to connect as many new users as possible. AA did in fact make money this way under the original contract, but the incentive diminished after the contract had been renegotiated and an extra environmental charge added to the cost of new connections.

The way in which the price was charged also created perverse incentives. Customers in expensive new buildings paid seven times more than other users consuming the same amount of water, and in this way subsidized their water consumption. Consequently, the company gained by first connecting high-income earners. Most users paid a fixed price. When the distribution network is enlarged, the marginal cost of connecting new customers will grow progressively higher, thus reducing the firm’s incentive for connecting more households. In addition, with a fixed price, users had nothing to gain by saving water.

As regards the weakness of the regulatory body, we have already mentioned its disadvantage in terms of information. Its gravest weakness, though, concerned political interference. ETOSS was controlled by politicians at national, regional, and local levels. They in turn represented a variety of political party allegiances, and so ETOSS was used for the pursuit of political advantages and its activities were frustrated by a good deal of political in-fighting. For example, the head of ETOSS was replaced far too frequently. To take another example, Aguas Argentinas was ordered to build infrastructure that was not provided for in the contract but that made possible a road construction project on which the mayor of Buenos Aires scored political brownie points. When the company wanted to raise the price of water to cover this extra expenditure, the mayor’s representatives in ETOSS put pressure on that agency to sanction a price rise that probably was unnecessarily high. The fact is that the executive power (the president) interfered in relations between AA and ETOSS and supported the enterprise, thereby weakening ETOSS still further.

Despite these weaknesses, water distribution in Buenos Aires is appreciably better today than it was before privatization. Actually, when the author visited Buenos Aires in February 2004, not one person expressed the opinion that water distribution is worse in Argentina now than prior to privatization. And the people interviewed include many who, if they thought so, had good reasons to say that the situation is worse now than before, such as journalists critical of privatization; the financial director of the regulator, which at the moment is in a legal dispute with AA; and ordinary people in the street such as taxi drivers.

Why, then, has there been so much debate in Buenos Aires about AA and water distribution? There are several reasons. First, Argentina is in a state of post-shock, despite economic growth of more than 8 percent in 2003 and 7 percent in 2004. The economic crisis was very severe, making the country drastically poorer. A large chunk of the middle class has found itself poor. Unemployment is rife. This made the discussion about the price of water more relevant to more people. Second, the atmosphere in the country is filled with nationalism and anti-globalization sentiments. The difference between the International Monetary Fund and Aguas Argentinas seems to blur, in many people’s minds. After all, they are both expressions of ‘‘international capitalism and Western neocolonialism,’’ the forces allegedly behind Argentina’s problems in the first place. And, as alluded to earlier, a foreign multinational is an obvious choice of scapegoat when politicians use blame games in order to cover up their own failures. It cannot be excluded that the nationalist and populist rhetoric that is rife in Argentina played an important role in the mobilization of privatization resistance in Buenos Aires. There are plenty of cheap political points to be made by pretending to work for the people and against a foreign multinational. In fact, this seems to be a common feature in the privatization debate. As William Finnegan, the New Yorker staff writer who broke the story about Cochabamba, mentioned earlier, notes, ‘‘the number of populists opposing water privatization seems to be effectively inexhaustible.’’ 141

Alexandre Brailowsky, head of Aguas Argentinas’ special program to reach the very poorest parts of Buenos Aires, has a lot to say about the situation. He has worked with water distribution in different parts of the developing world for many years. With a background in Doctors Without Borders, he gives the impression of being a veteran from the Paris 1968 student uprising and is hardly a neoliberal ideologue or your average ‘‘heartless and greedy corporate leader.’’ Therefore, it is especially interesting to experience the fervor with which Brailowsky rejects the claims and activities of anti-privatization NGOs in Europe and North America. He says that they know nothing about water distribution in the developing world and that they seem to have a very poor understanding of the real problems. In fact, he is quite upset with them. Other people in Buenos Aires argue along similar lines: ‘‘Perhaps you have efficient government in Sweden. In Argentina, we do not,’’ people say.

Manila

A third instance of privatization noted for its negative consequences comes from Manila, the capital of the Philippines. 142 Before the private sector was admitted, only 67 percent of Manila’s population were connected to the city water-supply network. Most of the poor residents were not connected, and instead were obliged to purchase bad water at high prices from local vendors who often charged 30 times the price of mains water. Millions of Manila residents, therefore, were spending as much on water as on rent. But poor coverage was not the only problem. Water, on average, was available for only 16 hours a day, and wastage was no less than 63 percent.

An NGO, usually very critical of privatization, tells us that ‘‘[l]ow pressure and illegal water siphoning caused contamination in the pipes, and waterborne diseases were common, increasingly through the early 1990s. In 1995, there were 480 cases of cholera in Manila, compared with 54 cases in 1991, according to the Philippines Department of Health. Reports of severe diarrhea-causing infections peaked in 1997 at 109,483 — more than triple the 1990 number.’’ 143

Against this background, it is easy to understand that people in Manila were not at all happy with the public water distributor. It was chronically inefficient and had far too many employees. Public water, quite simply, was badly managed, even though credits had three times been awarded by the World Bank to put things right.