Austrian Business Cycle Theory : On the Interest Rate and the Cambridge Capital Controversy

Critics of the ABCT believe that CCC constitutes a strong rejection of the austrian theory of capital. Apart from the empirical evidence of ABCT, one problem with the assumptions of the reswitching theory is that it assumes that ABCT is all about the change in capital-intensiveness following a change in interest rates. ABCT does not even depend on the change in interest rates per se, nor even on a "single" natural interest rate as some wrongly believed; Sraffa being just one of them. But as the reswitching technique theory implies the possibility of capital reversing, which is to say, the association between the nature of the production techniques employed and rate of interest is not a monotonic one. That is, a decline in interest rates might lead to a lengthening in the structure of production through more capital-intensive techniques, when at the same time a further decline in interest rates will trigger a drop in the length of the structure of production through less capital-intensive techniques. In other words, that relationship is U-shaped.

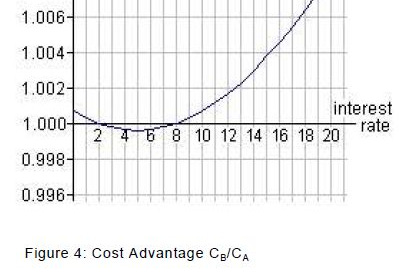

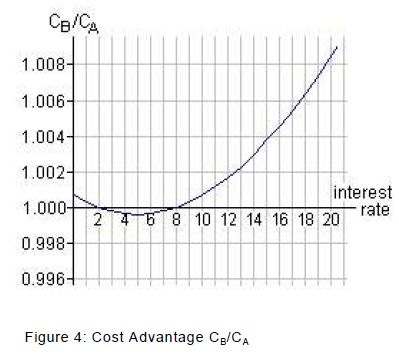

Graphically (from Roger Garrison, 2006), the reswitching phenomenon looks like :

Robert Vienneau exposes the reswitching (2006, 2010) as a refutation of the ABCT. That being said, one problem regarding reswitching is first about the empirical evidence. And it doesn't appear to be a very common phenomenon and casts doubt on its relevance in the real world. Young (2012) found evidence that the more roundabout industries have seen their industrial prices increased by more than the less roundabout, on the onset of the subprime episode. Besides, Roger Garrison expresses his doubts about the plausibility of the reswitching hypothetical example, as follows :

It may be worth noting that the hypothetical examples of reswitching invariably entail either implausibilities or trivialities. Samuelson's implausibly high interest rates cast doubts on the relevance of his hypothetical example. Clearly, though, Samuelson (p. 571) has little patience with those who would prefer to see the percentages that actually look like interest rates. He suggests that "The reader can think of each period as a decade if he wants to pretend to be realistic." In other words, if you don't want to think of 100% interest rates, then think of 30-year planning horizons! But even with this way of thinking, the cost advantage of the 20-year project is never as much as 15% unless the interest rate rises above a 200% DPR (decadal percentage rate) or falls to 0%, and the cost advantage of the 30-year project (at interest rates between 50% and 100% DPR) maxes out at about 1%.

My own example features interest rates of 2% and 8% and production periods of two or three years. Using such plausible ranges for interest rates and planning horizons gives us cost advantages that are minuscule. The cost advantage of the three-year project is 0.0763% at a zero rate of interest, and the maximum cost advantage of the two-year project (at a 5% interest rate) is 0.0408%. A 15% cost difference (of the three-year project over the two-year project) doesn't occur unless the interest rate is nearly 180% APR [i.e., annual percentage rate].

More broadly, austrian economists have obviously responded to the capital controvery issue on a theoretical ground in many ways, contrary to what it is sometimes argued.

But first of all, let's set up the question about the interest rates. Rothbard (1962 [2009], page 1003) declares that the boom is not necessarily accompanied by an absolute decline in interest rates but instead in a relative decline (i.e., what "would be" if this event did not occur). This means we may not observe it from the data even if it actually occurred :

Credit expansion always generates the business cycle process, even when other tendencies cloak its workings. Thus, many people believe that all is well if prices do not rise or if the actually recorded interest rate does not fall. But prices may well not rise because of some counteracting force – such as an increase in the supply of goods or a rise in the demand for money. But this does not mean that the boom-depression cycle fails to occur. The essential processes of the boom – distorted interest rates, malinvestments, bankruptcies, etc. – continue unchecked. This is one of the reasons why those who approach business cycles from a statistical point of view and try in that way to arrive at a theory are in hopeless error. Any historical-statistical fact is a complex resultant of many causal influences and cannot be used as a simple element with which to construct a causal theory. The point is that credit expansion raises prices beyond what they would have been in the free market and thereby creates the business cycle. Similarly, credit expansion does not necessarily lower the interest rate below the rate previously recorded; it lowers the rate below what it would have been in the free market and thus creates distortion and malinvestment. Recorded interest rates in the boom will generally rise, in fact, because of the purchasing-power component in the market interest rate. An increase in prices, as we have seen, generates a positive purchasing-power component in the natural interest rate, i.e., the rate of return earned by businessmen on the market.

We have a similar statement from Huerta de Soto (1998 [2009], p. 349) who declares that the relative lowering of the interest rate is even compatible with an increase in the interest rate in nominal terms, if the rate climbs less than it would have in an environment without credit expansion (for instance, if credit expansion coincides with a generalized drop in the purchasing power of money).

Of significant importance is Hayek's claim (2008, pp. 77-78), in Monetary Theory and the Trade Cycle (1933, p. 147), that a money rate of interest below the natural rate need not originate in a deliberate lowering of the interest rate by the banks. The same result can be achieved by an improvement in the expectations of profit or by a diminution in the rate of saving, which may drive the natural rate (at which the demand for and the supply of savings are equal) above its previous level. If the banks refrain from raising their rate of interest to a proportionate extent, this will enable a greater demand for loans, a demand not backed by an available supply of savings. It is clear that, unlike most (probably) modern austrian economists, Hayek put more emphasis on profits than on the interest rates.

And Ludwig Von Mises (1940, p. 50; 1949 [1996] pp. 558-559, 795) himself focuses on the credit (over)expansion, not the interest rate as such. When the amount of credit supply diverges from individuals' time preference, with more credit than people's willingness to wait, the entrepreneurs are left to believe there is more savings than what is actually available. Even an increase in the interest rate will not necessarily stop speculation and malinvestments to be accumulated if the borrowers are determined to complete the new capital goods stages which they begin to see threatened. Mises uses this example to say that the origins and end of the boom were not to be found in the interest rates but credit expansion.

This tendency toward a rise in the rate of originary interest and the emergence of a positive price premium explain some characteristics of the boom. The banks are faced with an increased demand for loans and advances on the part of business. The entrepreneurs are prepared to borrow money at higher gross rates of interest. They go on borrowing in spite of the fact that banks charge more interest. Arithmetically, the gross rates of interest are rising above their height on the eve of the expansion. Nonetheless, they lag catallactically behind the height at which they would cover originary interest plus entrepreneurial component and price premium. The banks believe that they have done all that is needed to stop "unsound" speculation when they lend on more onerous terms. They think that those critics who blame them for fanning the flames of the boom-frenzy of the market are wrong. They fail to see that in injecting more and more fiduciary media into the market they are in fact kindling the boom. It is the continuous increase in the supply of the fiduciary media that produces, feeds, and accelerates the boom. The state of the gross market rates of interest is only an outgrowth of this increase. If one wants to know whether or not there is credit expansion, one must look at the state of the supply of fiduciary media, not at the arithmetical state of interest rates. ...

If a bank does not expand circulation credit by issuing additional fiduciary media (either in the form of banknotes or in the form of deposit currency), it cannot generate a boom even if it lowers the amount of interest charged below the rate of the unhampered market. It merely makes a gift to debtors. The inference to be drawn from the monetary cycle theory by those who want to prevent the recurrence of booms and of the subsequent depressions is not that the banks should not lower the rate of interest, but that they should abstain from credit expansion.

The core of the ABCT is about the increase in money supply above people's demand for money due, for example, to monetary policy. Independently of the techniques being employed, a monetary overexpansion will distort the structure of production by diverting the investments that would have been made in the absence of monetary overexpansion. Because it focused specifically on the interest rate, the reswitching theory missed the target. Sraffa made the same mistake when arguing about "the" natural rate of interest, wrongly believing that ABCT depends on it. The multiple errors committed by Sraffa have been corrected by Guillermo Sanchez, in "Sraffallacies: A Misesian Defense of ABCT" (Part 1, & Part 2). And in two other posts.

Now, returning to the reswitching question, Huerta de Soto in Money, Bank Credit, and Economic Cycles (1998 [2009], pp. 574-575), argued that a fall in interest rates will trigger a lengthening in the production structure in the sense that a change in the techniques being used will not stop the decision to adopt a longer production process :

From the point of view of an individual actor or entrepreneur, once the prospective decision has been made to lengthen production plans (due to a rise in saving), all initial factors (land, labor, and existing capital goods) are subjectively deemed to be "original means of production" which merely determine the starting point of the production process. It is therefore irrelevant whether or not the new investment process incorporates techniques which, considered individually, may have been profitable at higher rates of interest.

What de Soto is saying here is that whether labor or capital goods, the initial factors of production are considered and treated as original means of production for already-planned additional stages. From this, it is obvious that technique switching will not stop ill-planned activities to be undertaken. In the below paragraph, de Soto (2009, pp. 573-574) reveals something even more interesting :

In other words, within the Austrian School model, if, at a drop in the interest rate, a former technique is revived in connection with a new investment project, this occurrence is merely a concrete sign, in the context of a particular production process, that this process has become longer as a result of the rise in saving and the fall in the interest rate.

And he gives the example of older (less capital-intensive) but re-used methods being incorporated into the new, lengthier structure of production, as an illustration of the evidence for the widening in production structure :

An increase in saving (and thus a decrease in the interest rate, other things being equal) may result in the replacement of a certain technique (the Roman plow, for instance) by a more capital-intensive one (the tractor). Even so, a subsequent drop in the interest rate may permit the reintroduction of the Roman plow in new production processes formerly prevented by a lack of saving (in other words, the established processes are not affected and still involve the use of tractors). Indeed a new lengthening of production processes may give rise to new stages in agriculture or gardening that incorporate techniques which, even assuming that production processes are effectively lengthened, may appear less capital-intensive when considered separately in a comparative static equilibrium analysis.

A similar point has been made by O'Driscoll & Rizzo (1985 [1996] [2002]). They advance the idea that the CCC considers the original factors in an objective way while austrian economics consider these in a subjective way. It is only given the subjective interpretation that we can conceive the entrepreneurs would consider as original factors all factors already in existence when they begin to formulate their plan to expand the production. Thus, under the subjective view, the re-introduction of a previous technique (supposedly less capital-intensive) is explained by the fact that entrepreneurs consider that this technique involves more roundaboutness than its earlier use.

The possibility of technique reswitching in this Cambridge sense was recognized by Hayek in the early 1940s (Hayek, 1941, pp. 76-7, 140ff., and 191f.), but neither he nor later Austrian theorists have seen this phenomenon as a threat to Austrian capital theory. If the theory is interpreted subjectively, the Cambridge challenge misfires. The blueprint of a production technique does not, by itself, fully define the economically relevant time element of the economy's production process. If increased savings cause entrepreneurs to commit additional resources to the earlier stages of production of a given production process, then the structure as a whole is more time-consuming. The fall in the rate of interest translates the now more distant time horizons of consumers into correspondingly more distant time horizons of producers. This result is quite independent of any change in the production technique employed. In the context of the Cambridge model, the Austrians would claim that the re-adoption of technique A involves more roundaboutness than its earlier employment. ...

Finally, it can be noted that the period of production is sometimes reckoned in terms of the time that elapses between the application of the so-called original factors and the emergence of the final output. The "original factors." a phrase that is usually interpreted to mean raw land and labor, has also been avoided in the present exposition. Again, the use of such terminology invites misinterpretation. It suggests not only an objectivist conception but also an historical orientation. Any attempt to impute economic meaning to the period of time between the objectively defined original factors and the resulting consumption activity will be in vain. With a subjectivist interpretation, factors of production have meaning only in the context of prospective consumption goods and the plans formulated by the entrepreneurs to produce these goods. All factors – land, labor, and capital – that were in existence when the entrepreneur's plan was first formulated can rightly be thought of as original factors.

... In the Cambridge formulation the rate of interest is treated as an exogenous variable. The changes in the interest rate that supposedly induce technique reswitching are themselves unaccounted for. This simply makes for bad theory – theory in which changes in the level of savings are neither a cause nor a consequence of changes in the rate of interest. In the reswitching models, the only change in production activities allowed for is a change in the technique employed. A change in the rate of interest either has no effect whatever or provokes a change in the production technique. The relevance of such a model – even to Böhm-Bawerk's formulation of Austrian capital theory – is questionable. And the particular way in which the analysis is carried out raises still further questions. Despite claims to the contrary, the fundamental distinction between the comparison of alternative equilibrium states and the description of the process by which the economy is moved from one state to another is hopelessly blurred. This is a virtually inevitable consequence of the failure to specify what particular preference or policy change caused the initial change in the rate of interest. While these aspects of Cambridge capital theory are grounds for dissatisfaction with the theory itself, they have been largely overlooked in the present treatment in order that the thematic distinction between subjectivist and objectivist views of a capital-using economy could be emphasized.

The relevant point to be kept in mind is that when these new stages have been artificially created by the unsustainable lengthening of the production structure following monetary overexpansion, the malinvestment process is taking place. Austrian theory must not necessarily specify that these new stages must incorporate relatively more capital intensive techniques. Because the key concept is price structure distortions owing to malinvestments.

In The Pure Theory of Capital (1941, p. 76) Hayek expresses the idea that the concept of the 'average period' of production is empty because of the extreme difficulty to determine which process is the longer.

It will probably be fairly obvious by now that as the complete processes of production with which we have to deal become increasingly complex it becomes more and more difficult, and may in some cases be impossible, to say in any general way which of several, alternative processes under consideration is as a whole the shortest or the longest. The total length of time which elapses between the very beginning of the process and the completion of the product may be shorter in one process than in another, and yet by far the greater part of the input used may be applied very early in the first process and very late in the second process. Which of these two processes is to be regarded as the longer ? It is impossible to answer this question at the present stage, and there is in fact no general answer to it. It is only mentioned at this point in order to warn the reader against any attempt to provide himself with an answer by introducing some concept of an "average period" of production. Such a concept, as we shall see, is not only unnecessary but is also highly misleading.

And Hayek continues (p. 77), arguing that an increase of capital is compatible with both a shortening and lengthening of the time of the production process :

At this point, however, one particular misunderstanding of the theorem that roundabout processes of production are more productive may be mentioned, as it is due to a confusion between these two concepts. It has sometimes been argued that an increase of capital is more likely to shorten than to lengthen the time during which we have to wait for the product. And this is quite true when we speak of the time interval which will elapse before a given quantity of output will emerge. But this is quite compatible with a simultaneous increase in the periods for which we have to wait for the product of particular units of input.

As he pointed out too, "Investment periods of particular units of input may change without any change in the technique of production used in any particular industry" (p. 78). In any case, to shorten the time of the process, or making it more round-about, one condition is that the investment period for some factors of production would have been longer than what they initially were.

The use of elaborate machinery may not only very much shorten the time it takes to turn the raw material into a finished product but even make the time between the moment when the first input is invested in the machinery and the moment when the first output emerges shorter than the period during which we had before to wait for the product. Yet this has been made possible only by investing some of the input used in producing the machinery for a much longer period than any had been invested before. 1

1 Cf. A. A. Young, 1929, p. 796: "The use of capital saves time, in the sense that a larger product can be had with a given amount of labour. But it increases the average interval of time which elapses before the products of a given day's labour reach their final form and pass into the hands of consumers."

Overall, Hayek argues (1941, p. 78) that the transfer of factors of production (i.e., inputs) from industries using shorter processes to industries using longer processes will leave the length of the period of production in any industry and methods of production of any particular commodity unchanged but instead would lead to an increase in the periods for which particular units of input are invested. But even so, the magnitude of changes in those mentioned investment periods will be "exactly the same as it would be if they were the consequence of a change in the length of particular processes of production." (p. 78). Hayek emphasizes (pp. 142-145) the combinations of the different factors of production. Under specific conditions, depending on the relative prices of different kinds of input and on the interest rates, one combination emerges as the longer, more time-consuming process, when given another set of relative prices, another combination will emerge as the longer process. This is because the amount of waiting depends on the interest rate but also on the investment period, and this, for anyone of the different kinds of input used (e.g., labour, raw material).

Actually we have to deal with a situation where first there are a great number of different kinds of input, and where, secondly, what is more important, the value of the product due to different units of input is variable and can be deliberately varied by using more or less of the particular kind of input in combination with given other kinds of input.

The first of these two circumstances means that in all cases where different kinds of input are applied in the different stages of anyone process of production, the relative amounts of waiting involved in different processes will depend on the relative values of the different kinds of input. In order to arrive at an aggregate figure of the amount of waiting involved in each process we have to assign definite weights to the different units of input, and these weights must necessarily be expressed in terms of value. But the relative values of the different kinds of input will inevitably depend on the rate of interest, so that such an aggregate cannot be regarded as something that is independect of, or as a datum determining, the rate of interest.

Still more serious is the second difficulty. This is directly connected with the fact already noted that in some cases only the input function (i.e. the range of periods for which we have to wait for the products of different units of input) and in other cases only the output function (i.e. the range of periods for which we have to wait for the different units of output) is directly given and that the one can only be converted into the other on the assumption that the rate of interest is given. This means that in many cases (in all cases where durable goods are concerned) we cannot say in any general way, and on purely technical grounds, how long the different parts of the total amount of input invested will remain invested. But this is not all. The fact that the value of any investment grows gradually (at compound interest) into the varying value of its product means that larger and larger quantities have to be regarded as being invested at each successive period for which the given investment is continued. If, e.g., the product of one year's investment of a given quantity of input is reinvested for another year, the amount that is reinvested includes the interest accrued on the original investment during the first year. And the result of investing a given quantity of input, at a given rate of interest, for two years will be larger than the result of investing twice the quantity of input for one year.

The effect of this is that the amount of waiting involved in a particular investment is not simply proportional to the length of the investment period and the value of the input invested, but is dependent also on the rate of interest. [1] In consequence, when we compare two different investment structures, it will not always be possible even to say, on purely technical grounds, which of them involves the greater amount of waiting. At one set of relative values for the different kinds of input and at one rate of interest, the one structure, and at a different set of values or a different rate of interest, the other structure, will represent the greater amount of waiting, or will be "longer" in the sense in which this term has commonly been used. If, e.g., we take two investment structures of processes of production in which labour and raw materials are used in different proportions but where at one set of relative prices of labour and the raw material the average investment period for the whole input is the same, a rise in the price of labour relatively to that of raw material will make the average period of the one of the two processes longer than that of the other, and a fall in the price of labour relatively to that of the raw material will have the opposite effect.

... No matter what procedure we were to adopt, the same technical combination of different inputs would, under different conditions, appear to correspond to different aggregate or average periods, and from among the different combinations sometimes one and sometimes another would appear to be the "longer". But as the size of the product will clearly depend on the technical combination of the different kinds of input, it obviously cannot be represented as a function of any such aggregate or average period of investment. All that we can say is that it depends on the combination of the different investment periods or waiting periods which are incommensurable in purely technical terms, and that ceteris paribus a change in anyone of these periods will cause some definite change in the size of the product. ...

In place of this unrealistic concept of an actual stock of consumers' goods, Böhm-Bawerk introduced [2] the more refined concept of the subsistence fund, which consists, not of ready consumers' goods, but of quantities of prospective or inchoate consumers' goods which are as yet only represented by intermediate products. This stock of intermediate products, however, would correspond to one definite quantity of consumers' goods, and therefore determine a single possible waiting period, only if all of the intermediate goods were completely specific in the sense that each of them could only be turned into a fixed quantity of consumers' goods maturing at a particular date. In fact it is only in exceptional cases that the goods of which the stock of capital consists are specific in this sense. As a rule the quantity of consumers' goods that is obtainable from a given intermediate product, and the date or dates when this quantity will become available, will depend, just as in the case of pure input, on how the good is used, i.e. with what kinds and quantities of other capital goods it is combined. A given stock of capital goods does not represent one single stream of potential output of definite size and time shape; it represents a great number of alternatively possible streams of different time shapes and magnitudes.

And of particular significance is that capital-intensity, according to Hayek (1941, pp. 286-287), is really about the changes in capital intensity essentially at the between-industry level, not really at the within-industry level. That is to say, what the monetary expansion has caused is in fact a transfer of the factors of production (or inputs) in favor of the growing sectors of the economy. The technique of production (and its capital intensity) may not have changed in any of the industries. Therefore a switch of the techniques occurring among individual industries is irrelevant from the austrian standpoint. In Hayek's words :

An increase in the relative amount of consumers' goods offered for capital goods, or a fall in the rate of interest, will cause an expansion of those industries which use more capital in proportion to labour than others do, while the inverse case will favour the industries using relatively little capital. More or less capital will be used in industry as a whole, not because the proportion between capital and labour (and consequently the technique of production) has changed in anyone industry, but only because the relative size of the groups of industries using comparatively much and comparatively little capital respectively has changed. The technique of production may have changed in none of the industries. All the different products may still be produced in the same manner as before. And yet the investment periods of the individual units of input which have been transferred to the expanding industry will have increased. What has happened is simply that the industries whose costs of production have been reduced more than those of others by the fall in the rate of interest have expanded at the expense of the second group.

The last sentence makes crystal clear that even in this aforementioned case, the austrian malinvestment theory still holds insofar as monetary overexpansion stimulates the relatively more capital-intensive industries at the expense of the less capital-intensive ones.

As Hayek (1941, p. 73) pointed out, a fall in interest rates involves essentially the use of processes which yield a higher rate of profit, not necessarily the longer process as such. This means that austrian malinvestment theory has to do with the distortion of what would be relatively more profitable and what would be less in the absence of monetary overexpansion, leading to a change in the pattern of investments.

Among the wide range of possible methods of production known at anyone time there will be some which will yield their product after shorter periods of time and some which will not yield it until after longer periods. From among each group of methods involving the same "amount of waiting" – if we may make provisional use of this vague term – the one that will be chosen will be the one which yields the greatest return from a given investment of factors. But so long as there is any limitation on the "amount of waiting" for which people are prepared, processes that take more time will evidently not be adopted unless they yield a greater return than those that take less time.

The reswitching does harm to neoclassical economics because it assumes the homogeneity of capital. Ludwig Lachmann, in On Austrian Capital Theory (p. 92), argues that the heterogeneity of capital (a key element in austrian economics) implies that the actual capital combination must be changed, modified, and with it, older capital goods discarded and newly capital goods added. It does not imply a simple addition of capital goods but a restructuration :

One result of the recent discussion on "reswitching" is to the advantage of the Austrian school. As long as all capital is regarded as homogeneous, managers may respond to a marginal fall in the rate of interest by a marginal act of substitution of capital for labor. But heterogeneity of capital entails a regrouping of the existing capital combination; some capital goods may have to be discarded, others acquired. It is no longer a marginal adjustment that is called for but entrepreneurial choice and decision. As Pasinetti pointed out, "Two techniques may well be as near as one likes on the scale of variation of the rate of profit and yet the physical capital goods they require may be completely different."

In a world of disequilibrium, entrepreneurs continually have to regroup their capital combinations in response to changes of all kinds, present and expected, on the cost side as well as on the market side. A change in the mode of income distribution is merely one special case of a very large class of cases to which the entrepreneur has to give constant attention. No matter whether switching or reswitching is to be undertaken, or any other response to market change, expectations play a part, and the individuality of each firm finds its expression in its own way. Yet only "reswitching" has of late attracted the interest of theoreticians. There is more in the world of capital and markets than is dreamt of in their philosophy.

Of relative importance, and which should be kept in mind is the fact that "a marginal act of substitution of capital for labor" holds true only if we assume homogeneity of capital, a notion that makes obviously no sense at all. Furthermore, in light of Pasinetti's comment on reswitching in the above citation, Lachmann (1940, p. 25), in Capital, Expectations, and the Market Process, writes :

A capital structure is an ordered whole. How does it come into existence? What maintains it in the face of change, in particular, unexpected change? These are questions that now claim our attention. A capital structure is composed of the capital combinations of various firms, none of which is a simple miniature replica of the whole structure. What makes them fit into this structure? Wherever we might hope to find answers to these questions, it must be clear that they cannot be found within the realm of macroeconomics. Capital combinations, the elements of the capital structure, are formed by entrepreneurs. Under pressure of market forces entrepreneurs have to reshuffle capital combinations at intervals, just as they have to vary their input and output streams. Change in income distribution is just one such force. "Capital reswitching" in a world of heterogeneous capital is merely one instance of the reshuffling of existing capital combinations.

Another defense of ABCT is from Kirzner, in Essays on Capital and Interest (pp. 8-11), who adresses the reswitching paradox by critizing its oversimplified model. The problem originates from the logic of deriving an aggregated investment period from individual and different techniques :

This premise is that each technique of production involves a simple, unidimensional 'quantity' of time, such that different techniques can be unambiguously 'objectively' ranked as involving greater or lesser quantities of time (or waiting). In fact, there is no reason at all to accept this premise. The cases that yield the capital-reversing paradoxes all arise from production processes involving more or less complex dating patterns for inputs and outputs. (In a stylized example made by Samuelson (1966), a given quantity of output can be obtained in year 4 from one technique that calls for the input of two units of labour in year 1, and six units of labour in year 3; or alternatively by a second technique of production calling only for the input of seven units of labour in year 2.) It appears obviously mistaken (or at least to involve an arbitrary and possibly misleading oversimplification) to wish to collapse the possibly incommensurable quantities of time associated with individually dated input components of a given complex production technique into a single simple unidimensional quantity of time.

The main cause is that, due to the different patterns of waiting in the techniques such that A is more profitable at high and low interest rates and B is more profitable at medium levels, averaging and rank-ordering the techniques in terms of "overall" time-consuming method is an ambiguous procedure. Kirzner concludes :

If then we find that, as interest falls from very high levels to below r2, technique A is replaced by technique B, while when interest continues to fall even lower and reaches below r1, technique B is replaced, in turn, by technique A (which had been preferred at very high rates of interest), we should not, surely, conclude that at one of these two switch points the reduction in interest has perversely brought a change to a less time-consuming technique. Rather, we should understand that comparing the complex, multidimensional waiting requirements for different techniques simply does not permit us to pronounce that one technique involves unambiguously less waiting than a second technique. (... There is no need ... to rank the two techniques in terms of their overall waiting requirements.) They involve different patterns of waiting, such that both very low and very high rates of interest might make technique A seem the more profitable, while at the intermediate rates it is technique B that is the more profitable. There is nothing perverse about this, unless one mistakenly insists that one or other of these techniques involves the greater quantity of time, or of waiting. 7

Hayek (1941, pp. 69-70, 142) has expressed more or less the same idea :

If the variation in the technique of production used always either affected the investment period of only one unit of the input or else affected the investment periods of all units in the same direction, there would be no problem, and we should be able to speak of changes in the "period of production", or the "length of the process as a whole", as a short way of referring to changes in the investment periods of the various factors used. In fact, however, most of the changes in productive technique are likely to involve changes in the investment periods of different units of input to a different degree and perhaps in different directions. ... In particular it makes it impossible to use the terms "changes in investment periods" and "changes in the length of the process" or "changes in the period of production" synonymously. It must indeed appear doubtful whether the second and third of these concepts, which necessarily refer to aggregates of investment periods, have any clear meaning.

... because the different waiting periods cannot be reduced to a common denominator in purely technical terms. This would only be possible provided we had to deal with only one homogeneous kind of input ...

The most important fact, and also less known by most criticism, is that it is not the interest rate that matters most but instead the (expected) rate of profit, as shaped by relative prices distorted by money supply. Hayek (1941, pp. 388-389; see also pp. 199-201) has provided this well made counter :

It is evident and has usually been taken for granted that methods of production which were made profitable by a fall of the rate of interest from 7 to 5 per cent may be made unprofitable by a further fall from 5 per cent to 3 per cent, because the former method will no longer be able to compete with what has now become the cheaper method. It is true, however, that it is scarcely possible adequately to explain this, if one thinks only of the direct effect of a change in the money rate of interest on cost of production, and does not proceed to consider the changes in relative prices which ultimately govern the profitability of the various methods of production. It is only via price changes that we can explain why a method of production which was profitable when the rate of interest was 5 per cent should become unprofitable when it falls to 3 per cent. Similarly, it is only in terms of price changes that we can adequately explain why a change in the rate of interest will make methods of production profitable which were previously unprofitable.

The most important conclusion, then, which emerges from this discussion is that the method of production that will be adopted, or the proportional amount of capital that it will be profitable to use, will depend not on the rate of interest at which money can be borrowed but on the relations between different prices and the shape of the profit schedule (or investment demand schedule) as determined by these price differences. And these relative prices will in turn depend on the relative scarcity of the various kinds of resources compared with the direction of demand. The rate of interest will, in the main, determine only to what point on the schedule investment will be carried, that is, it will determine only the marginal rate of profit, and, through the latter, it will exercise a minor influence on the volume of ontput that it is profitable to produce with a given demand. The volume of investment, however, will depend as much if not more on how much investment it will be profitable to undertake in order to obtain a certain output. And with a high "rate of profit" any given marginal rate of profit will be reached with relatively little investment per unit of output, because with a high rate of profit the investmend demand schedule will be steep, while with a low "rate of profit" the same marginal rate of profit will only be reached with much more investment per unit of output, because the investment demand schedule will be flat. [1]

Earlier, Hayek (1939, pp. 15-16, 27-29, 32-33, 64-67) has explained that what affects the tendency to produce with less or more capital is the shift in the position of the profit schedule but not in the interest rates. More significantly, even when the interest rate fails to rise at the late stage of the boom the employment in capital-intensive industries experiencing a fall in the demand for their products must decline due the rise of the rate of profit on short as compared with that on long investments which induces entrepreneurs to divert whatever funds they have to invest towards less capitalistic machinery. Under certain situations, the rate of interest could fail to follow the movements of the rate of profit. When it happens, the rate of profit will substitute its role in shaping, determining business plans.

If, by keeping the rate of interest at the initial low figure, marginal profits are also kept low, this will only have the effect of a reduction in cost, that is, it will raise the figure at which the supply of and the demand for final output will be equal; but it will not affect the tendency to produce that output with comparatively less capital, a tendency which is caused, not by any change in the rate of interest, but by the shift in the position of the profit schedule.

...

If the rate of interest had been allowed to rise with the rate of profit in the prosperous industries, the other industries would have been forced to curtail the scale of production to a level at which their profits correspond to the higher rate of interest. This would have brought the process of expansion to an end before the rate of profit in the prosperous industries would have risen too far, and the necessity of a later violent curtailment of production in the early stages would have been avoided. But if, as we assume here, the rate of interest is kept at its initial level and incomes and the demand for consumers’ goods continue therefore to grow for some time after profits have begun to rise, the forces making for a rise of profits in one group of industries and for a fall in the demand for the products of another group of industries will become stronger and stronger. The only thing which can bring this process to an end will be a fall in employment in the second group of industries, preventing a further rise or causing an actual decline of incomes.

...

So far our main conclusion with respect to the rate of interest, rather borne out by recent experience, is that we might get the trade cycle even without changes in the rate of interest. We have seen that if the rate of interest fails to keep investment within the bounds determined by people’s willingness to save, a rise in the rate of profit in the industries near consumption will in the end act in a way very similar to that in which the rate of interest is supposed to act, because a rise in the rate of profit beyond a certain point will bring about a decrease in investment just as an increase in the rate of interest might do.

The reswitching paradox appears crystal clear now. The error was to consider the interest rate as being the fundamental cause behind the technique reswitching while, in reality, the relative prices (or profits) were really what mattered most. The distortion of those relative prices through money expansion can indeed predict the technique reswitching. This reveals those attacks on the ABCT to be misleading and completely outside the point.

References.

Garrison, R. W. (2006). Reflections on Reswitching and Roundaboutness. Money and Markets: Essays in Honor of Leland B. Yeager, 186.

Hayek, F. A. (1933). Monetary theory and the trade cycle. (N. Kaldor & H. M. Croome, Trans.). New York: Sentry Press.

Hayek, F. A. (1939 [1969]). Profits, Interest, and Investment: and Other Essays on the Theory of Industrial Fluctuations. AM Kelley.

Hayek, F. A. (1941 [2007]). The Pure Theory of Capital (Vol. 12). University of Chicago Press.

De Soto, J. H. (1998 [2009]). Money, Bank Credit, and Economic Cycles, 2nd Edition. Ludwig von Mises Institute.

Kirzner, I. M. (1996). Essays on Capital and Interest: An Austrian Perspective (p. 103). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Lachmann, L. M. (1940 [1977]). Capital, Expectations, and the Market Process. Kansas City.

Lachmann, L. M. (1976). On Austrian Capital Theory. In Dolan Edwin G. (Eds.), The Foundations of Modern Austrian Economics, 836.

O'Driscoll, G. P., Rizzo, M. J., & Garrison, R. W. (1996). The Economics of Time and Ignorance. London: Routledge.

Rothbard, M. N. (1962 [2009]). Man, Economy, and State, 2nd Edition. Ludwig von Mises Institute.

Vienneau, R. L. (2006). Some Fallacies Of Austrian Economics. Online verfügbar über die Homepage des Social Science Research Network: http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm.

Vienneau, R. L. (2010). Some Capital-Theoretic Fallacies in Garrison's Exposition of Austrian Business Cycle Theory: A Research Note. Available at SSRN 1354336.

Von Mises, L. (1940 [2011]). Interventionism: An Economic Analysis. B. B. Greaves (Ed.). Liberty Fund.

Von Mises, L. (1949 [1996]). Human Action: A Treatise on Economics. Ludwig von Mises Institute.