Although the stagflation of the 1970s has severely, if not entirely, discredited Keynesian theories, politicians persist in adopting these costly keynesian policies in order to stimulate economic activity, by stimulating demand, and by the same account investment, through an increase of public deficits which would be paid in the future by economic agents. Keynesian policies continue to be promoted despite the theoretical flaw that 1) the revival in consumer spending would not distort the production structure by destroying the stages of production further from consumption 2) such policies could stimulate investment by penalizing private savings; the combination of 1) and 2) underlying a consumption of capital would cause a destruction of the capital required for the renewal of capital equipment that allows the sustainability of the consumption level. In addition to the theoretical flaws, empirical evidence also fails to validate the Keynesian prescription.

Introduction

In an effort to boost hiring and job creation and to invest in a variety of domestic infrastructure programs, Congress passed and the president signed the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA), commonly known as the economic stimulus package, in 2009. ARRA represented one of the largest peacetime fiscal stimulus packages in American history.

We collected over 1,300 anonymous, voluntary responses from managers and employees that allow us to better understand what happened at the organizations that received contracts funded by ARRA spending.

Organization-level responses

We asked organizations whether it was easier to find “high-quality workers” than before the 2008 financial crisis. Here the simple results tell the story: Of the 159 non-profits and 67 firms that responded to the question, half of each group (80 and 34, respectively) said hiring was easier than before the crisis. Of the other half, 11 percent and 16 percent, respectively, believed hiring was harder now, and the rest claimed it was just as hard (or equivalently, just as easy) as before the crisis. Both of these harder-to-hire results are statistically significantly different from 0 percent at the 5-percent level. Among the 135 government organizations answering the question, 41 percent said it was easier to hire now, 10 percent said it was more difficult, and the rest indicated no change.

The Hiring-funding relationship

A natural question is whether organizations that found it easier to hire good workers received a disproportionate share of the stimulus. We found little evidence that this was the case. Multiple statistical specifications, including the ones presented in Tables 3 and 4, failed to find a significant relationship (at a 95-percent confidence interval) between the percentage of an organization’s annual revenue coming from ARRA and whether that organization found it easier to hire. Similarly, we find no evidence that organizations that received more total stimulus dollars (as measured by an organization’s tier) found it easier to find good workers.

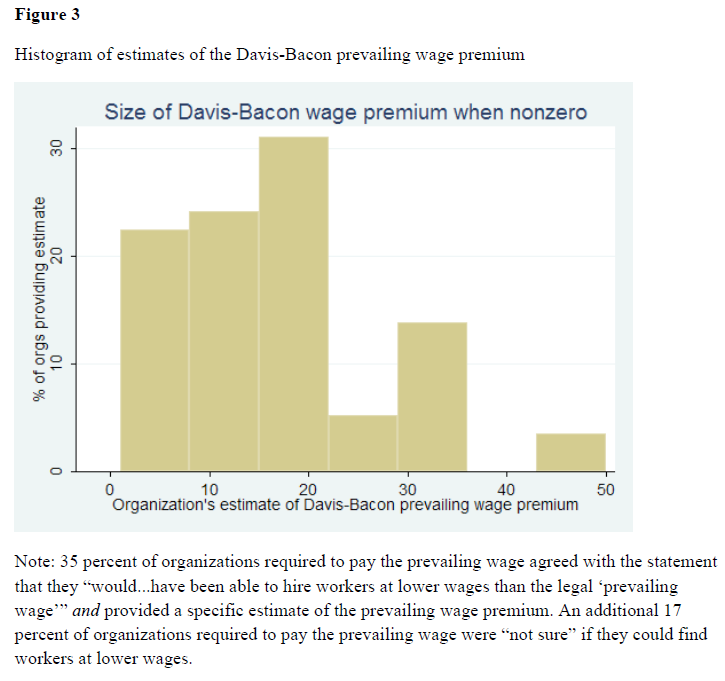

We asked organizations whether Davis-Bacon applied to them, and if so, whether they could have hired equivalent workers at wages lower than the prevailing wage. If they responded “yes,” we also asked by what percentage they could have reduced offered wages and still attracted comparable workers.

Our median respondent who reported Davis-Bacon wages were above the market level said that Davis-Bacon wages were 13.3 percent higher than market wages; the mean response was 14.9 percent. Since only 35 percent of Davis-Bacon organizations said prevailing wages were above market wages (with an additional 17% unsure), one might with due caution conclude that Davis-Bacon wages are 6 percent above the market level on average.

How well targeted was the stimulus?

We now turn to the question of whether ARRA funds went to organizations with organizational slack, i.e., organizations with downtime.

We asked organizations whether, before they received their ARRA-funded contracts, “things had been slow,” “things had been busy,” which caused them to turn work down, or “things had been busy,” and ARRA funding just made them work harder. Only 14 organizations indicated that they turned down other work in order to take on ARRA projects; but by a 2:1 ratio, respondents indicated that they had “been busy” before ARRA and so “worked harder” with ARRA funding rather than indicating that “things had been slow” before receiving ARRA funding (305 organizations chose the former response, 152 the latter). Probit results indicate that firms who said things had been slow (with a 1-0 indicator; there was no natural ordering for an ordered probit) were not more likely to be in the best-funded tiers. Further, only in the univariate regression was the ARRA fraction of a firm’s revenue a reliable predictor of past slowness (Tables 6-8); this result fell to insignificance after including the most cursory controls. Again, one must interpret voluntary survey responses with due caution, but it appears that for the majority of organizations, ARRA was not a lifeline during a time of deep economic trouble: it was a new burden to carry. Once again, ARRA did poorly under Summers’ “targeted” test.

Worker responses

Did stimulus-funded projects hire the unemployed or the already employed? Our surveys indicate a near-tie on this question. Of the 277 respondents hired after January 31, 2009, 42.1 percent had been unemployed immediately beforehand and 47.3 percent had come directly from another job. Of the rest, 4.1 percent had been out of the labor force, and 6.5 percent had been in school. Thus, the weight of the evidence suggests that ARRA did an enormous amount of “job shifting” rather than “job creating.” There is evidence of the latter, but, under Keynesian reasoning, every worker hired away from another job reflects some weakening of the stimulus.

But by no means was our sample an unusually fortunate group. Among the post-ARRA hires unemployed immediately before taking their current position, one-fourth had their unemployment benefits run out, and one-third had been out of work for over 26 weeks. Nor were these workers who had great power to pick and choose their jobs: only 14 percent had turned down a job market offer before taking the current position, and 36 percent had taken a pay cut compared to their previous positions.

One question of great interest to labor economists is whether workers attempt to use up their unemployment benefits before taking a job. We found no evidence for this: only 17.8 percent of respondents said they had started their job within a month of their benefit expiration. If 17.8 percent of workers accepted a job every month, this would yield 9.8 percent of workers unemployed for a year or more, even less than the 17.8 percent found in our sample.

Jonathan Chait suggests that some unemployed workers should now be able to take the place of workers who left their jobs for the ARRA-funded organizations; if true, keynesian policies could be more successful than suggested by the paper. But subsidized firms can hire already employed and already unemployed workers because they have an advantage over the non-subsidized firms. If the non-subsidized firms could find easier to hire new workers without external help, why should the government need any fiscal stimulus package to create new jobs ?

No Such Thing as Shovel Ready: The Supply Side of the Recovery Act

Under the commission of the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, we conducted a first-of-its-kind study, sending interview teams across the country to ask businesses, nonprofits, and local governments just what the stimulus program accomplished. Researchers interviewed representatives of 85 different organizations, drawn from a random sample in five different metropolitan areas, and learned about their experiences applying for and receiving contract and grant funding under ARRA.

Our interview teams wrote and called stimulus-receiving firms and organizations at random, with the only preference being toward organizations receiving higher amounts of ARRA funding.

Did the Stimulus Create Jobs in the Real World?

Let’s begin with a success story. The owner of a construction engineering firm told our team that ARRA is "the only reason our doors are still open." He didn’t suggest having to sacrifice quality in order to meet the ARRA’s strict deadlines. (Our interview teams rarely asked specifically about the quality-speed tradeoff, but many interviewees brought up the issue themselves). And because of ARRA, his small firm grew by about 20 workers, of which 6 had been brought off of unemployment. Thus, ARRA saved his firm, he found good-quality workers quickly, and he worked on a project that seemed to be no different than the usual federal construction project. That is what a success story looks like, and this is about as good a story as we found.

But even in this success, there are problems for the Keynesian free-lunch theory of stimulus: half a dozen workers came from the unemployment lines, but from where did those other fourteen workers come? They came from other firms, creating a genuine trade-off: more person-hours at one firm meant fewer person-hours at another. This raises substantial questions about how many of the jobs created or saved by ARRA were actually new jobs rather than employees plucked from one firm to work on an ARRA contract. And this substantially undermines both the value creation and job creation criteria we identified on the first page. Similarly, one project manager for a federal agency brought on five workers to administer ARRA funds. But of these five "new" hires, two hires were agency retirees who came back to work and through a special exemption drew ARRA-funded salaries while continuing to receive retirement benefits, one hire was transferred from another location, one hire came from a full-time job in the private sector, and one had been employed elsewhere in a temporary job.

The organizations we interviewed often didn’t reveal or didn’t know if their new hires were unemployed beforehand; but in some cases, they pointed out that they either hired workers from the private sector or brought retirees back into the labor force. More often, firms just told us they hadn’t created that many jobs — they just used their own workers more (15) and just hired some temps for a few days or weeks.

(15) If stimulus-funded firms produce their extra output largely by using their own full-time workers harder — a common theme in interviews — then as a matter of accounting stimulus funds would largely accrue to owners as higher profits. When firms hold onto little-used workers during a recession, Keynesians refer to this as "labor hoarding."

As mentioned above, we also found evidence that ARRA often created work without creating jobs: we heard many versions of, "Things were slow until the stimulus money came along; ARRA gave our employees something to do." In Keynesian terms, these organizations were labor hoarding, holding onto workers through the slowdown even though they didn’t have much work to do. In these cases, ARRA funds boosted profits by plugging a hole in the company’s revenue stream; whether or not ARRA actually saved jobs at labor-hoarding firms is still a matter of speculation. To summarize our job creation findings: job switching: yes; giving a company’s current workers more to do: certainly. But hiring people from unemployment was more the exception than the rule in our interviews.

The Tradeoff between Speed and Quality

At least 12 of the respondents brought up concerns about the quality of stimulus-funded projects relative to other public projects. Some said that the federal government’s push to spend money was hurting the project’s quality; several said stimulus dollars were funding projects that were far down the list of needs, and a few voiced a general worry that while they were doing good work, they thought the government workers overseeing ARRA were so overworked that it was bound to hurt quality. To some extent the tradeoff was a result of the ill-defined goal of being "shovel-ready." Several respondents suggested that this was not a meaningful phrase for the large infrastructure projects that the popular imagination considered ARRA to be funding. For instance, one state transportation manager suggested that "shovel ready" was an arbitrary distinction that did not comport with the realities of infrastructure building, saying, "It takes years of permitting work, environmental analysis, et cetera, to get to the shovel ready stage, and millions of dollars. Who’s going to get that far and then stop on a project that’s really important? It doesn’t make sense."

Tiny Tiles

One federal contractor who installed tile in government buildings said that he had planned to install some typical four-inch white tile, the kind he had used in countless government projects beforehand — the very tiles specified in the architectural renderings. But a revised project specification issued by the contracting agency required him to use a smaller, more intricate set of colored tiles. The contractor told our team that installing the smaller tiles would increase his labor costs alone by 50 percent and the only reason he could see for using the smaller tiles was to move the money out the door on the ARRA schedule. Installing tiny tiles isn’t quite as bad as digging ditches in the morning and filling them up in the afternoon — at least the government got some nice tiles. But this practice almost surely adds too little value to justify the cost. Accordingly, the link between funds spent and value created is not as direct as proponents of fiscal stimulus often assume, especially when the government is in a hurry to get the money out the door.

A Good (and Idle) Firm is Hard to Find

Six of the organizations we interviewed, primarily engineering firms, said that there was little or no change in their work level due to the stimulus. They were niche firms with services in high demand. When they took ARRA work, they were turning down other work. These six were an extreme version of what many firms told our teams: The lunch wasn’t nearly as free as advertised. Tradeoffs mattered, and skilled firms and workers were scarce even in a world of 10 percent unemployment.

From the perspective of normal government efficiency and accountability, hiring skilled and reliable firms is good federal contracting practice: if the federal government finds a high-quality firm, there’s good reason to stick with them. But when the ostensible goal of ARRA spending is "targeting" slack sectors of the economy, this contracting is a complete Keynesian failure. Unfortunately for Keynesian theory, no contract officer wants a scandal, especially on a high-profile program such as ARRA, so funding will flow to firms least likely to create boondoggles. That means funds will often go to firms that are already quite likely to be busy, firms that are likely to stick to trusted workers, firms that are unlikely to take a chance on the long-term unemployed.

Red Tape: Driving Out the Best Firms?

"Some contractors really have avoided ARRA contracts simply because of the reporting requirements." — Owner of a Veteran-Owned Construction Firm

Many of the firms our teams interviewed complained about ARRA’s detailed reporting requirements, especially the time and energy required to learn the reporting system. While there’s room for improvement, such complaints seem to stem from the nature of bureaucracy, not failures of Keynesian theory.

One assisted-living facility turned down an extra $15,000 per stimulus-funded worker because they couldn’t navigate the ARRA bureaucracy.

“No Such Thing as Shovel-Ready Projects”

Table 2 sums up some basic descriptive statistics from our interview sample. Some federal contractors, maybe most, took the stimulus funding in stride, and hired at least a few unemployed workers, boosting wages and profits. But for at least a third, the stimulus failed the theoretical assumptions of Keynesianism in important ways.

As Barack Obama himself acknowledged “there’s no such thing as shovel-ready projects” :

When the president campaigned for the stimulus package at the start of his presidency, he and others in his administration repeatedly insisted the investments would go to "shovel-ready" projects -- projects that would put people to work right away. As recently as August, however, local governments were still facing delays spending the money they were allocated from the stimulus, CBS News Correspondent Nancy Cordes reported.

It is worthwhile to recall that :

Furthermore, the spending wasn't timely: Three years after the law was adopted, some programs still have managed to spend only 60 percent of the appropriated funds. Not only was the spending poorly timed, it also wasn't targeted. The data show that stimulus money wasn't targeted to those areas with the highest rate of unemployment.

Each of these studies highlights the wide gap between the keynesian ideal and the best the government can do.

Further reading : No Correlation : What If Keynesian Stimulus Did Not Work ?