The Cambridge Capital Controversy (CCC) is sometimes cited as one of the strongest refutations of the Austrian Business Cycle Theory, considered by Mark Blaug as “the final nail in the coffin of the Austrian theory of capital” (Huerta de Soto). As mentioned elsewhere, one would preferably think about the interest rate(s) as the expected rate(s) of profits. That is, monetary over-expansion would deceive entrepreneurial expectation of future returns. Hayek (1941, pp. 388-389) even says it was the rate of profit itself (with the relative prices that shaped it) and not the interest rate that matters most. Other Austrians answered to the CCC challenge but differently than Hayek.

We must also point out that the reswitching controversy has apparently no empirical consequences. Indeed, several research point out that “reswitching technique” is a peculiar argument: firstly because theoretically its occurrence becomes increasingly small as the number of sectors increases and even tends to zero as the number of sectors tends to infinity, and secondly because it does not appear to be a common phenomenon (Han & Schefold, 2006; Kersting & Schefold, 2021; Schefold, 2022, 2023).

Theoretically, Guido Hülsmann, in “The structure of production reconsidered”, had investigated the issue. He explains that the pure rate of interest (PRI) and the production structure are not necessarily negatively related (i.e., a lower interest rate is related to a lengthening of the structure of production) even though the interest rate still affects relative spending, as theorized by austrians. He proposes to develop and enrich the theory of the structure of production. He lists 8 possible scenarios, each of them having different implications. He finally investigates the implication of the consumer credit and the variation of monetary conditions. The former simultaneously thins and lengthens the structure of production. The latter has no systematic impact on the structure of production.

Interestingly, the scenarios (1°, 3°, 6°, and 7°) implying a drop of the PRI also involve higher relative spending toward the upstream stages, and an increase in savings (to the exception of 7°). The eight scenarios can be summarized as follows :

Scenario 1° : increase of savings at a constant demand for savings, lower PRI, increase in gross savings rate, lengthening of the structure of production, monetary revenues fall, real revenue of savers-investors increases, real revenue of owners of original factors increases more strongly.

Scenario 2° : increase of savings and of demand for savings, constant PRI, strong increase in gross savings rate, lengthening of the structure of production, monetary revenues fall, real revenue of owners of original factors increases, real revenue of savers-investors increases more strongly.

Scenario 3° : increase of savings at a constant demand for savings, strong decrease of the PRI, increase in gross savings rate, no lengthening of the structure of production, activity shifts from stages of production downstream to stages of production upstream, monetary revenues fall, real revenue remains constant for savers-investors while increasing for owners of original factors.

Scenario 4° : increase of the demand for savings with no increase in savings, higher PRI and gross savings rate, lengthening of the structure of production with a thinning of the higher stages (with exception of stages newly created), monetary revenues fall, real revenue increases for savers-investors while remaining constant for owners of original factors.

Scenario 5° : decrease of savings with increase in demand for savings, higher PRI, constant gross savings rate, lengthening of the structure of production, relative spending diminishes toward the upstream (with exception of stages newly created), monetary revenues remain constant, real revenue increases for savers-investors while diminishing for owners of original factors.

Scenario 6° : increase of savings with decrease in demand for savings, lower PRI, constant gross savings rate, shortening of the structure of production, relative spending increases toward the upstream (with the exception of the stages that disappear), monetary revenues remain constant, real revenue diminishes for savers-investors while increasing for owners of original factors.

Scenario 7° : decrease of the demand for savings at a constant supply of present goods, lower PRI and gross savings rate, shortening of the structure of production, widening of the higher stages (with the exception of the stages that disappear), monetary revenues increase, real revenue increases for savers-investors while remaining constant for owners of original factors.

Scenario 8° : decrease of savings at a constant demand for savings, higher PRI and a lower gross savings rate, lengthening of the structure of production with a thinning of the higher stages (with exception of stages newly created), monetary revenues increase, real revenue remains constant for savers-investors while decreasing for owners of original factors.

Scenarios 1°, 2°, 3° and 4° entail higher growth, 5° and 6° have no impact on growth, 7° and 8° entail lower growth.

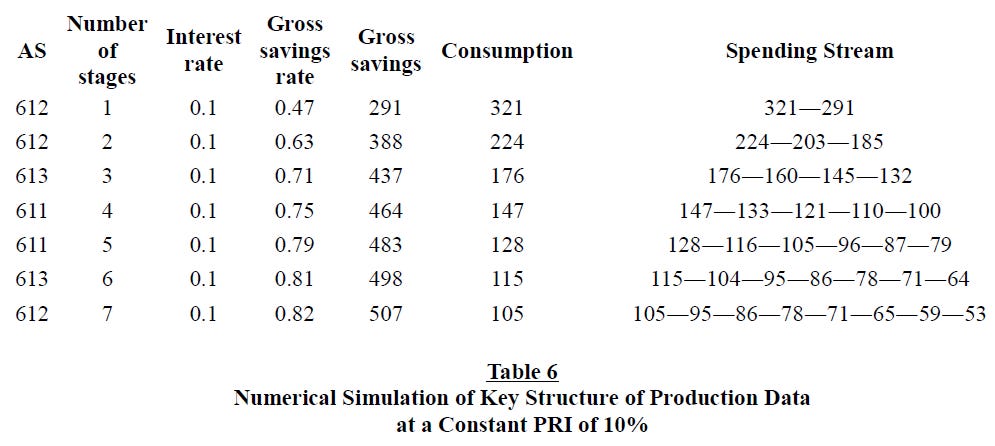

In the above tables, ‘n’ represents the length of the structure of production, ‘i’ the interest rate and ‘s’ the gross savings rate.

Hülsmann, Jorg Guido (2011). The structure of production reconsidered. Université d’Angers: GRANEM Working Paper no. 2011-09, 34, 1-62.

Abstract: This paper reassesses the concept of the structure of production in light of recent works by Fillieule (2005, 2007) and Hülsmann (2008). In particular, we reconsider the relations between three structural variables: the interest rate, the gross savings rate, and the length of the structure of production. Based on this reconsideration, we study three basic growth mechanisms in a monetary economy that can be applied to various scenarios that seem to be relevant under the contemporary conditions of the world economy. We also discuss the role of human capital and of consumer credit within the structure of production.

The Conventional Account of the Structure of Production

Flows of Goods within the Structure of Production

[...] The horizontal extension of Figure 2 represents monetary spending in exchange for the supply of non-monetary goods, while the vertical extension represents the passage of time. The figure is most usefully read bottom-up. At the very bottom, consumer spending of 100 oz of gold is identical with the revenue of the stage of production furthest downstream. Out of these 100 oz, 15 oz are spent, in the next period, on original factors needed in that stage; and 80 oz are spent, also in the next period, on capital goods needed in that stage. Thus there is a residual income of 5 oz (100-15-80=5), which is the pure return on capital invested in that stage. Next consider the revenue and expenditure of the stage most closely upstream. This stage produces capital goods. Its total revenue is 80 oz, subsequent spending on original factors is 16 oz, subsequent spending on higher-order capital goods is 60 o, and the residual income is 4 oz. The next three stages can be interpreted in exactly the same manner. Then, in the stage furthest upstream, there is no more spending on higher-order capital goods. Revenue in this stage is 20 oz, 19 of which are subsequently spent on original factors, and 1 oz constitutes residual income.

[...] The Aggregate Gross Revenue (418 oz of gold) is the sum of all gross incomes, including the gross incomes of the capitalists (100+80+60+45+30+20=335), the gross incomes of the owners of original factors (15+16+12+13+8+19=83), and the gross incomes of the entrepreneurs (0). Entrepreneurs earn no profit and incur no loss in equilibrium, and thus their gross aggregate revenue is zero under the above hypothesis of an evenly rotating economy. For the same reason, there is no net saving respectively net investment. All savings are used to reproduce, again and again, exactly the same time structure of production.

The aggregate net revenue of the owners of original factors is exactly equal to their aggregate gross revenue (83 oz) because, by definition, factor owners do not need to make expenditures to reproduce these factors. Similarly, the net revenue of entrepreneurs is equal to their gross revenue, because according to the definition used by Rothbard, entrepreneurs do not operate with any money of their own and thus have no expenditure to make. By contrast, the net revenues of the capitalists are not equal to their gross revenues. Rather, they merely earn the residual income, left over from gross revenue after the deduction of all productive expenditure. Since the capitalists in the above example earn an Aggregate Gross Revenue of 335 oz, out of which they save and spend a total of 318 oz on higher-order capital goods and on original factors, their net income is 17 oz.

Notice that aggregate net revenue (83+17=100) is equal to the aggregate sum spent on consumption, a necessary implication of the evenly rotating economy. For the same reason, the rates of return earned in the different stages of production are exactly equal to one another, and thus identical with the pure rate of interest. Indeed, different rates of return in different stages of production would imply that the economy is in disequilibrium.

Savings-Based Growth

Rothbard then proceeds to illustrate a savings-based growth process. The increase of gross savings (in Figure 6, this would correspond to a shift of the supply schedule of present goods to the right) by definition goes in hand with a reduction of consumer expenditure, and it entails a reduction of the pure rate of interest (new intersection with the demand schedule).

This leads to the following adjustments of the time structure of production. On the one hand, because consumer expenditure is being curtailed, less revenue is being earned, and thus less money is being spent on factors of production, in the consumers’ goods industries and in the industries closest to consumption. On the other hand, the pure interest rate drops, which means that the spread between revenue and cost expenditure diminishes in each stage of production. Because one firm A’s costs are nothing else but the revenues of its suppliers, it follows that the revenues of all factors of production (and in particular the revenues of any firm B supplying the firm A with capital goods) tend to increase relative to the revenue of A.

Thus an increase of savings entails always a net loss of aggregate revenue in the consumer goods industries. But for the revenues earned in the capital-goods industries, it entails two opposite tendencies. On the one hand, these revenues tend to fall because the reduction in final consumer spending triggers through the entire revenue chain. On the other hand, these revenues tend to increase relative to final consumer spending because the triggering of revenues is based on a lower discount rate.

It follows that non-specific factors of production (such as capital, labour, and energy) will be reallocated, leaving industries “downstream” and entering industries “upstream;” while specific factors, which by definition cannot be reallocated, will earn permanently higher revenues upstream, and permanently lower revenues downstream. To the extent that reallocation is possible, new industries will be created at the higher-order end of the structure of production. 5

5 It is imaginable that the savings-induced reallocation of capital does not change the structure of production, under two conditions. The first one is that all factors except for capital be specific, so that they could not be reallocated. The second is that technological innovation be impossible, for lack of ideas or because of legal barriers. Under these two conditions, an increase of savings, combined with a drop of the interest rate, would leave the structure of production unchanged, and entail a mere redistribution of revenue, to the benefit of the owners of the specific factors needed upstream, and to the detriment of savers and of the owners of the specific factors needed downstream.

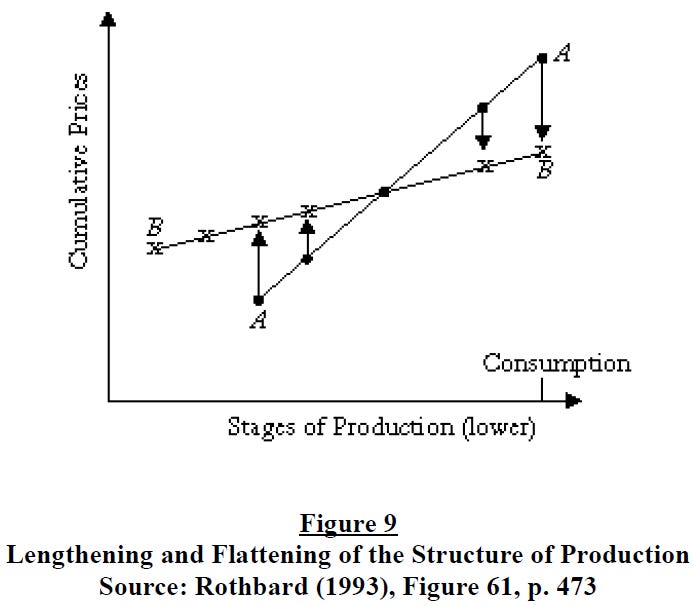

Rothbard illustrates this process with the above Figure 6, which is a simplified version of the above Figure 2. The initial structure of production is represented by the rectangles A-A, whereas the new structure of production is represented by the rectangles B-B. What has happened? On the one hand, the structure of production has become “flatter” because [it starts] from a smaller base of consumer expenditure (the B-rectangle at the bottom is smaller than the A-rectangle). On the other hand, the structure has become “lengthier” because there are now additional stages upstream (the top two B-rectangles) that did not exist before.

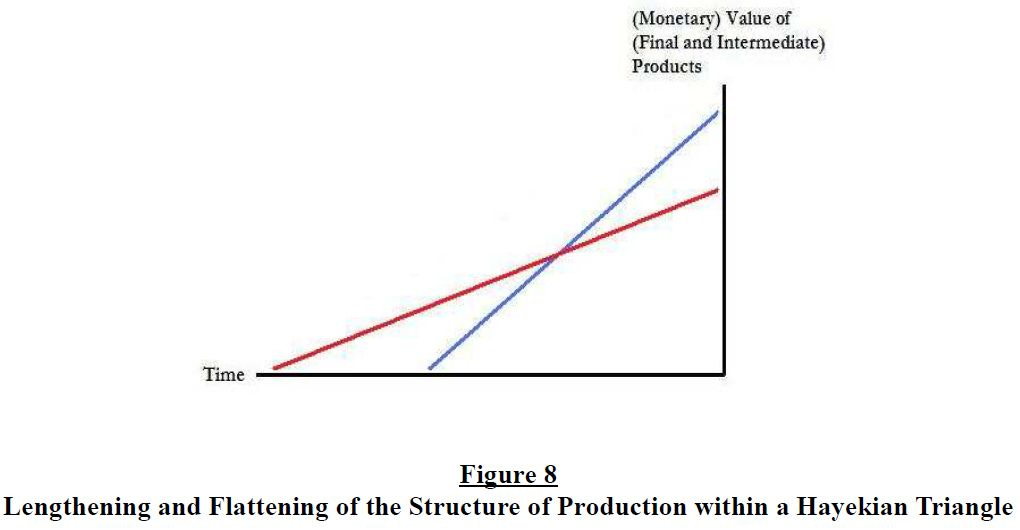

A similar illustration is based on the so-called Hayekian triangle. In Hayek, Garrison, and others, it is a triangle.

The simultaneous lengthening and flattening of the structure of production can then be illustrated by the shift from the blue to the red curve in the following figure:

But this is not quite correct, because spending in the last stage is not zero, even if only original factors are used. Rothbard is therefore correct in modifying the Hayekian figure into a trapezoid of the following form:

The point of these figures is to illustrate how the economy can grow based on higher savings, even if there is no variation whatever on the side of monetary factors. In mainstream conceptions there prevails the notion that growth cannot occur unless it is accommodated by a corresponding increase of aggregate demand. The Austrian analysis shows that, even if aggregate spending (and thus aggregate revenue and aggregate demand) does not change, growth can occur, resulting from a lengthening of the average period of production.

Notice that, in distinct contrast to mainstream conceptions of the role of the interest rate, the declining interest rate is not per se a cause of economic growth. It is merely conducive to the lengthening of the structure of production, and it is precisely the lengthening of the structure of production that entails economic growth. Indeed, as Menger (1871) has pointed out, the longer the overall process, the more natural forces can be substituted for human labour, thus liberating labour for additional productive ventures. The result is a higher average physical productivity per capita.

Two Critical Annotations

Impact of Changes of the Demand for Present Goods

As we have seen, the conventional Austrian model more or less exclusively focuses on the ramifications of an increase of the supply of present goods (more precisely, of savings) on the time structure of production, under the assumption that the demand for present goods remains constant. This assumption is unobjectionable. However, it does not always hold true in reality, and therefore it is useful to analyse the impact of changes of the demand for present goods.

Increases of the demand for present goods may result from any one of the following factors, or a combination thereof:

(a) immigration, implying a greater supply of labour hours (future goods) in exchange for money; immigration may in turn result (i) from deteriorating economic conditions in the immigrants’ homeland and (ii) from lower transport costs;

(b) a greater willingness to work, demonstrated by the supply of additional labour hours in exchange for money;

(c) discoveries of additional supplies of raw materials (future goods) that can be exchanged for money;

(d) the invention and development of new technologies that allow to use known supplies of raw materials at lower costs, thus increasing the supply of raw materials (future goods) that can be exchanged for money;

(e) a greater willingness to incur the risks of debt (producer credit and consumer credit).

[...] For example, the invention and development of new technologies that allow to produce capital goods at lower costs may entail an increase of the production of these capital goods (implying a higher demand for present goods) if the demand for them is sufficiently elastic. But if the demand for them is not elastic enough, or even inelastic, then those new technologies would result in a decrease of the demand for present goods.

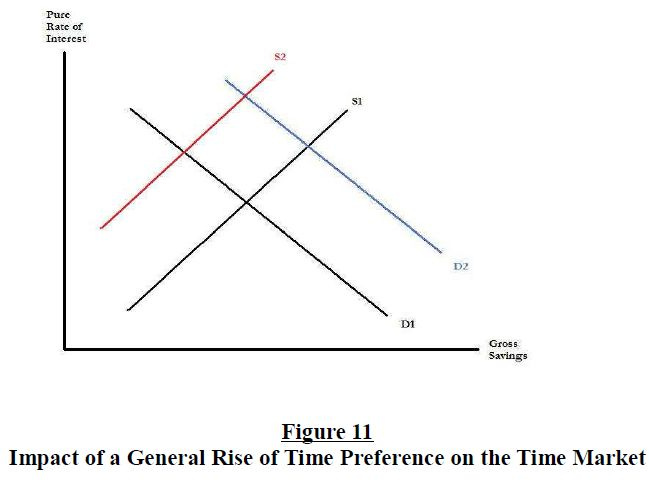

[...] Taking account of variations of the demand for present goods leads to results that are at odds with the conventional Austrian model of the relationship between time preference and the volume of savings, respectively the volume of investment expenditure. In the conventional model, a reduction of the market participants’ time preference schedules entails a higher supply of present goods at a constant demand for present goods, thus leading to a reduction of the PRI and to an increase of gross savings. However, Rothbard argues that on the time market both supply and demand are exclusively determined by time-preference schedules. It is therefore incoherent to assume that a reduced time preference would modify the supply schedule only, and leave the demand side unaffected. Rather, one would have to infer that a general reduction of time preference tends to affect both sides of the market (see Figure 11).

It would tend to increase the supply of present goods and, at the same time, tend to reduce the demand for present goods. As a consequence there will be a reduction of the PRI, but the volume of gross savings (and thus the volume of aggregate investment expenditure) will not be systematically affected. The latter could remain constant, or slightly increase, or slightly decrease, depending on the contingent circumstances of each particular case.

Inversely, a general increase of the market participants’ time preference schedules would simultaneously reduce the supply of present goods and increase the demand for present goods. On the time market, the PRI would therefore tend to increase, while aggregate investment expenditure, respectively the volume of gross savings, would not be systematically affected.

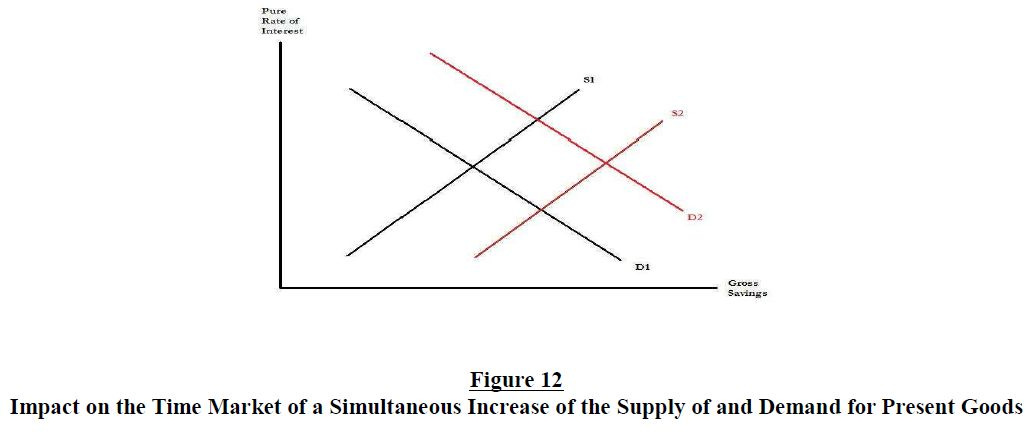

If one assumes that the demand for and the supply of present goods can simultaneously move in the same direction, then even more combinations are possible. Figure 12 show that, if the supply of present goods increases along with the demand thereof, then the volume of gross savings tends to increase, while the PRI will not be systematically affected. (Inversely, if for analogous reasons both the supply of and the demand for present goods diminish, the opposite effects will result.)

The Relationship between the PRI and the Length of Production Reconsidered

[...] Total spending at each stage is equal to the total spending at the previous stage discounted by a factor equal to the PRI, and the PRI is by definition the same for all stages of production. In our above example, the PRI is 15 percent, rounding errors being neglected for the sake of simplicity. Thus total spending on the products of the second stage (138) is equal to 159 divided by (1+0.15); total spending on the products of the third stage (120) is equal to 138 divided by (1+0.15), respectively it is equal to 159 divided by the square of (1+0.15); and so forth. In other words, our spending stream is a geometric sequence of the following sort:

C ; C(1+i) ; C(1+i)2 ; C(1+i)3 ; …; C(1+i)n

It follows that aggregate spending (by definition equal to aggregate demand respectively to aggregate gross revenue) within this stylised structure of production can be calculated as follows:

AS=C+C(1+i)+C(1+i)2+C(1+i)3+…+C(1+i)n

Equation 1 Aggregate Spending within a Simplified Structure of Production

Aggregate spending in our example is 611 tons of gold (159+138+120+104+90=611). Because of the hypothetical constancy of monetary conditions, the aggregate gross investment of 452 tons (611-159=452) is necessarily equal to aggregate gross savings, which corresponds to a gross savings rate of about 73 percent (452 divided by 611). The structure of production is in equilibrium at a PRI of about 15 percent and a length of 4 stages. [...]

Suppose that there is an increase of the supply of present goods (savings) and that therefore the time market settles at a PRI of 2 percent and aggregate gross savings of 518 tons of gold (which makes for a 84 percent gross savings rate). Because savings increase by 66 tons, there must be a corresponding reduction of consumer expenditure, which falls from 159 to 93 tons.

Suppose that the demand for present goods, for whatever reason, is very inelastic around the initial equilibrium and that, as a consequence, the increase of savings entails essentially a strong drop of the PRI from 15 to 2 percent, whereas aggregate gross savings only increase from 452 to 453 tons of gold. [...]

The structure of production has become shorter, despite the slight increase of savings and the very substantial drop of the PRI. This result squarely contradicts one of the main tenets of conventional Austrian capital theory, according to which the PRI is always negatively related to the length of the structure of production. [...]

The reason for the apparent irregularity that we have just discussed is that the PRI is not negatively related to the roundaboutness of production (to the number of production stages). Rather, it is precisely the other way round. 8 The higher the PRI, the higher is the discount between the revenues of any two stages; in other words, the higher the PRI, the higher is the difference between revenue and cost expenditure in each stage. But if there is no change in aggregate demand, and if (as in our example) consumer expenditure is by and large stable, then this can only mean that a higher PRI “pushes investment expenditure back” further upstream. [...]

Even if consumer spending remains constant, as in our simulation, there is an absolute decrease of business spending in each stage, with a snowballing tendency as one moves upstream. Where does the spending go? It can only go upstream, creating adding new stages of production and thus lengthening the overall production process.

Table 5 also shows that there is a ceiling for the possible level of the PRI. At the gross savings rate assumed in the above example, the ceiling seems to be around a PRI of 34 or 35 percent. As the PRI approaches this ceiling, its impact on the length of the structure of production grows exponentially. Moreover, it can be inferred from Table 5 that there is a minimal number of stages for each gross savings rate that does not depend of the PRI. In the above case, for example, it is impossible to have less than three stages, because the gross savings of 453 tons of gold cannot be profitably spread out over only one higher stage, with consumption expenditure in the first stage of only 158 tons. [...]

Notice that, at increasing gross savings rates, the minimal number of stages increases whereas the ceiling on the PRI diminishes. In other words, an equilibrium structure of production can accommodate any gross savings rate, if only the PRI is sufficiently low.

[...] at any given the PRI, more savings imply lower consumer expenditure, so that downstream investment expenditure will decline accordingly. The only place where this spending can go is further upstream, creating new industries for higher order goods.

The numerical simulation displayed in Table 6 is based on a constant PRI of 10 percent, again omitting rounding errors. The figures suggest that there is ceiling for the possible level of the gross savings rate. Such a ceiling must exist for any positive PRI because the revenue of the last stage cannot be zero or less. Moreover, it can be inferred from Table 6 that there is no minimal number of stages for each PRI. [...]

We have demonstrated that increases of the pure interest rate tend to lengthen the structure of production, rather than to shorten it; and inversely, a lower PRI tends to entail less roundabout production processes. [...]

Figure 19 is a graphical illustration of the first three lines of Table 5, in which we had given a numerical simulation of the key structure of production data at a constant gross savings rate of 74 percent. Because the gross savings rate does not vary, total consumer expenditure is always 158 tons of gold, and total savings (equal to total investment expenditure) is always 453 tons. At an interest rate of 2 percent (top green line), the 453 tons of savings are spent within three stages of production; at an interest rate of 14.5 percent (middle red line), the 453 tons of savings are spent within 4 stages; and at an interest rate of 21.7 percent (bottom blue line), it needs 5 stages to spend those 453 tons.

Now let us briefly turn to the second question we raised above, namely, the question pertaining to the meaning of the positive relation between the PRI and the length of the structure of production. What is the economic role or function of a lengthening of the structure of production resulting from an increase of the pure rate of interest? There is at least one function that we have already stressed in a different context, although at the time were still holding the conventional model to be accurate. In Hülsmann (2009) we have highlighted the fact that a higher PRI thins out the upstream stages. Fewer investments are made upstream and these investments earn a relatively high return, which means that the firms are relatively safe from insolvency. Yet this means nothing else but that the structure of production becomes more robust. Unforeseen events have a less dramatic impact on the solvency of the different firms and, thus, on the stability of entire network of firms. In short, higher interest rates switch the structure of production into “safety mode.” Inversely, a lower PRI enlarges the upstream stages. Relatively more investments are now made upstream, and in each stage firms operate at lower margins. The economy is therefore more vulnerable to unforeseen events.

Toward a Richer Theory of the Structure of Production

Structural Variables

Figures 15 and 17 illustrate the important fact that not all combinations of the structural variables (s, i, and n) are possible in final equilibrium. For example, at a given length of the structure of production, the higher the gross savings rate, the lower must be the PRI, lest there be no equilibrium at all; and inversely, the higher the PRI, the lower must be the gross savings rate. The explanation of this fact is that there is a quantitative relationship – though not a constant one – between the structural variables. For the simplified setting that we have considered in our previous discussion – notably assuming that all originary factors are used only in the most upstream stage – this quantitative relationship can be derived from Equation 1, which we have introduced above:

AS=C+C(1+i)+C(1+i)2+C(1+i)3+…+C(1+i)n

Equation 1 Aggregate Spending within a Simplified Structure of Production

Equation 1 contains absolute spending variables, namely, aggregate spending (AS), aggregate consumer expenditure (C), and – by implication – aggregate gross savings (S). It is therefore tempting to misread the equation, as suggesting that the structure of production depends on absolute spending levels. However, the equation can be transformed and reduced to a relation between the structural variables (for the derivation, see Appendix II). Thus one obtains the following Equation 2:

s= (1+i)n-1- 1(1+i)n- 1

Equation 2 Cardinal Relation between the Gross Savings Rate (s), the Pure Rate of Interest (i), and the Number of Stages of Production (n) in a Simplified Setting

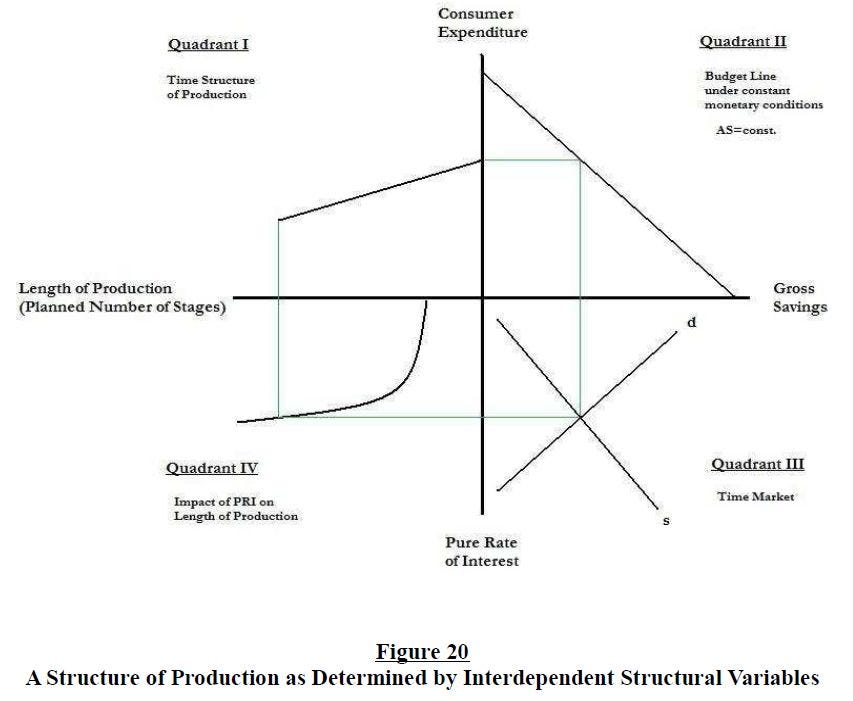

As a pedagogical device, we propose to summarise the basic interdependence between the structural variables with a four-quadrant graphical illustration (Figure 20) featuring the following panels:

(I) a panel representing the time structure of production, in the form of a Rothbardian trapezoid;

(II) a panel representing the macroeconomic budget line expressing the fact that monetary conditions (demand for and supply of money) determine aggregate spending, which in turn is composed of aggregate consumer expenditure and aggregate investment expenditure (equal to gross savings); 9

(III) a panel representing the time market; 10

(IV) and a panel representing the relation between the PRI and the length of the production structure (our above Figure 14).

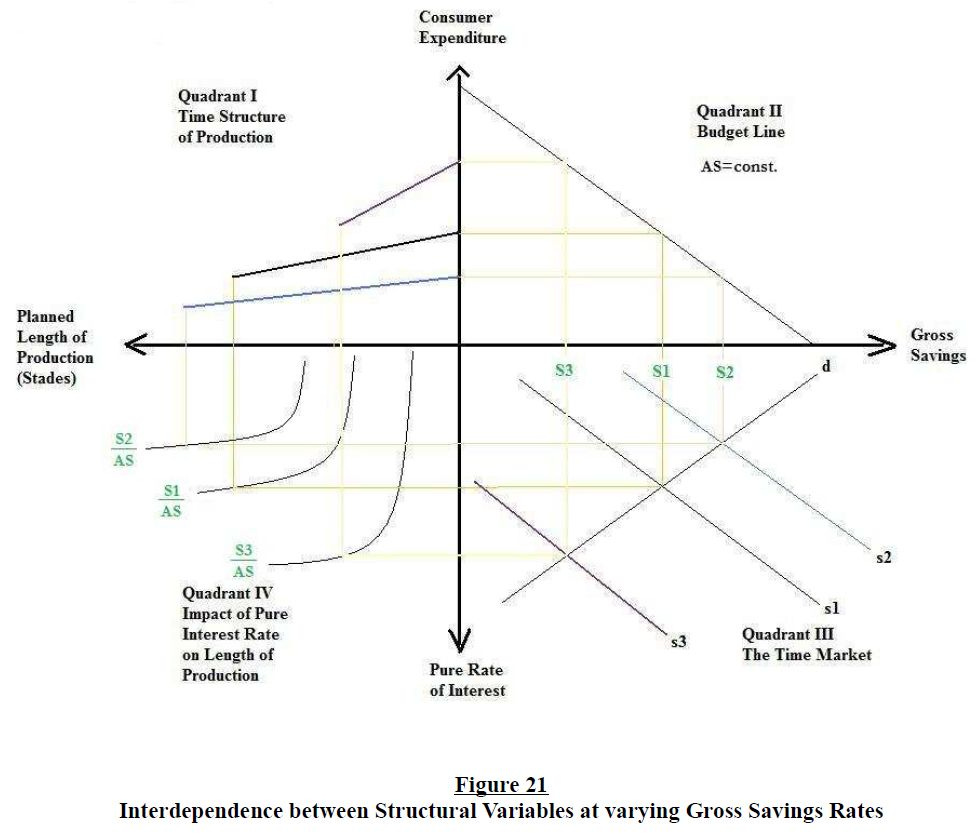

[...] Let us now proceed to show how this graphical tool can be used to illustrate modifications of the structure of production. As a first step consider the type of modification that has centre stage in the conventional Austrian account of savings-based growth, respectively of dis-saving and capital consumption. Figure 21 (below) represents three different final equilibrium situations. The first one is the initial equilibrium displayed in Figure 20 characterised by an initial total volume of gross savings (S1) and a corresponding gross savings rate of S1/AS. The second equilibrium represents a lengthening of the structure of production subsequent to an increase of gross savings (from S1 to S2) along with a drop of the PRI. The third equilibrium represents a shortening of the structure of production due to capital consumption. It results from a drop of gross savings (from S1 to S3) along with a rise of the PRI. As we have seen in the previous chapter, the impact of the PRI on the roundaboutness of production depends on the gross savings rate. To take account of this fact, in Quadrant IV we therefore have to replace Figure 14 with Figure 15.

Human Capital

It is customary to distinguish between original factors of production (land, labour) and produced factors of production (capital goods). However, original factors very rarely exist in their state of nature. Most of them have been altered through various acts of production. They include an original component and a capital component. A piece of arable soil is composed of the original land and the various modifications designed to make it more easily arable and abundant. Similarly, each human person is a complex living being, endowed with various original attributes, talents, and aspirations of a physical, intellectual, and spiritual kind, as well as with additional “cultural” attributes, dispositions, abilities, and aspirations that have been produced through a long-winding and ongoing educational process. … What makes a human being truly a “person” is a cultural achievement. We can call a person’s cultural acquisitions the human capital of that person.

Capital-Based Growth: Basic Mechanisms

[...] (1) A change of relative spending between upstream and downstream stages may result from the mere lengthening of the structure of production – that is, even if the PRI does not change. The creation of additional stages upstream ipso facto changes relative spending within the structure of production. The new stages create producer goods that make human labour in the downstream stages more productive. The lengthening therefore tends to entail growth.

(2) There can also be a change of relative spending within the time structure of production that results from the decrease of the interest rate. If the PRI drops, there is a simultaneous widening of the upstream stages resulting from greater expenditure, and a thinning of the downstream stages resulting from decreased expenditure. Even if the overall length of the structure of production did not increase, the relative widening of the upstream stages would have a similar effect as the previously discussed lengthening. It would attract more labour and capital upstream, thereby increasing the output of producer goods that make human labour in the downstream stages more productive. Hence, a relative widening of the structure of production, too, tends to entail growth even if the overall length of the structure of production does not increase.

(3) Finally, increases of the gross savings rate, even if they do not affect relative spending between the different stages, increase investment spending and therefore increase the revenues of employed as compared to unemployed factors of production. They therefore create incentives for the owners of hitherto unemployed factors to sell respectively rent them out on the market. In short, increases of the gross savings rate tend to make more factors of production available, thereby increasing the total physical output of the economy.

[...] Sometimes the mechanisms work in opposite directions. For example, a drop of the demand for present goods entails a lower PRI and a lower gross savings rate than would otherwise have occurred. The lower PRI then increases relative spending in some of the upstream stages and on that account entails growth, whereas the drop of gross savings reduces factor revenues and therefore factor employment.

Scenarios of Growth and Distribution Growth Scenario I

Let us start our analysis with the scenario conventional Austrian scenario of savings-based growth. It is characterised by an increase of the gross savings rate at a constant demand for present goods. This entails a drop of the PRI and also a lengthening of the structure of production. Hence, this scenario has the unique feature of positively combining all three basic growth mechanisms. It is therefore the strongest possible growth scenario. [...]

How does this scenario affect monetary and real revenues in the new final equilibrium? What can be said about its impact on the final distribution of revenues? The general tendency of monetary revenues is to fall, because the vigorous growth occurs at constant monetary conditions, thus entailing a significant drop of the price level (growth deflation). This fall will be most moderate in the case of the owners of non-specific factors such as labour and energy resources (coal, gas, etc.). Their monetary revenues will tend to equal their discounted marginal value product (DMVP), which is roughly speaking equal to the arithmetic product of their marginal physical product (MPP) and the price of this physical product, divided by the interest rate. 16 In the present scenario, the MPP increases whereas the interest rate falls. On that account, therefore, the DMVP of factors of production tends to increase. However, the falling price level entails an opposite tendency, so that on that account the DMVP of factors tends to diminish. Again, the overall result depends on the particular situation of each factor. Some non-specific factors might end up earning higher monetary revenues, while others will earn less than before. The general tendency is for a slight decrease because of the strong drop of the price level.

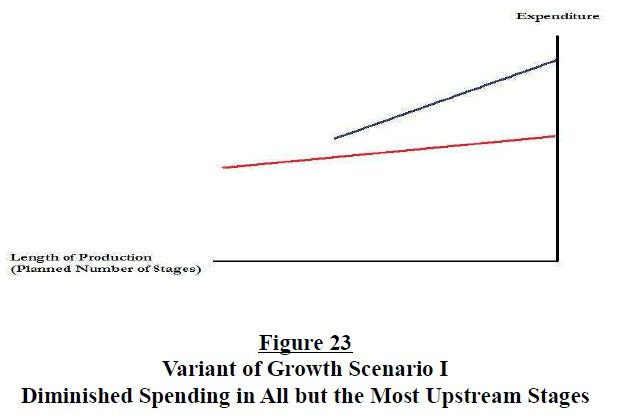

The owners of specific factors of production used in the upstream stages might even end up earning higher monetary revenues. This depends on the extent of the increase of the savings rate. In Figure 22, we see that, in the new equilibrium, monetary spending is higher in some of the upstream stages than before, and that it creates entirely new incomes in the additional stages created most upstream. However, consider the following variant of Growth Scenario I, in which the gross savings rate drops so much so that it diminishes spending in all but the new stages:

In this case it is likely – though not necessarily the case – that all factors except for the specific factors used in the new stages will earn lower monetary incomes than before.

What about savers-investors? Their interest incomes are subject to two opposite forces. On the one hand, they save and invest more and on that account obtain more interest payments. On the other hand, the interest rate drops and on that account they earn lower interest payments. The overall result depends on the particular circumstances of each case. We therefore have to say that the present scenario does not have any systematic implications for the monetary revenues of savers-investors.

Now let us turn to the new final distribution of real revenues. From the outset it is clear that the latter will strongly increase in the aggregate, because total monetary spending remains constant whereas the price level plunges. For savers-investors this implies that their real revenues will tend to increase. As we have seen, their monetary revenues will not be systematically affected, and thus the drop of the price level entails a tendency for their real interest revenue to increase. The increase of real revenues is even more clear-cut in the case of the owners of original factors. Indeed, their real revenue tends to be equal to their marginal physical product (which strongly increases) divided by the interest rate (which declines).

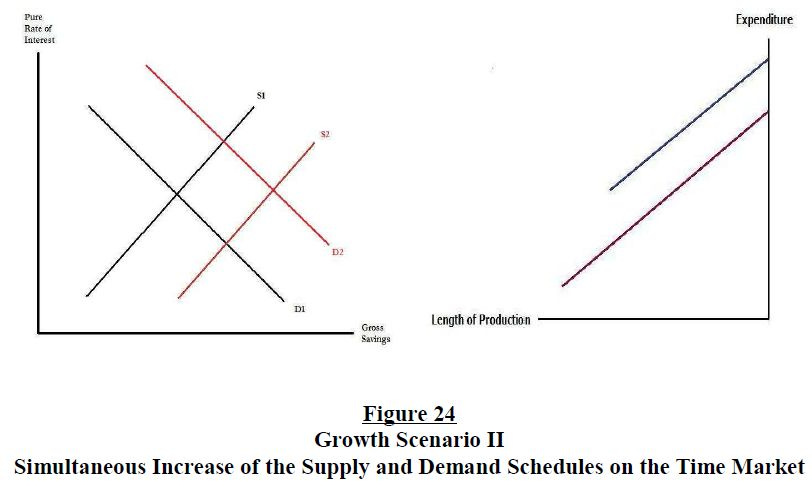

Growth Scenario II

Our second growth scenario is characterised by a simultaneous increase of the gross savings rate and of the demand for present goods. These changes have no systematic impact on the PRI, and thus there is no relative change of spending on that account. However, the gross savings rate is substantially higher in the new structure, which is therefore much more physically productive on that account. Moreover, the new structure is much lengthier, because with a PRI that is by and large unchanging, the greater volume of savings can only be invested upstream. Thus there are two growth mechanisms at work, and the third growth mechanism is neutral. We estimate that this is the 2nd most growth-friendly variation of the time market and the production structure.

As far as monetary revenues are concerned, the general tendency is for them to fall, again because the growth deflation. What we have said in Scenario I concerning the monetary income of the owners of original factors of production applies in the present scenario by and large as well. (The only difference concerns the fact that in Scenario II spending drops in all stages, except for the new stages that are being created upstream.) One would have to expect that wages and rents remain stable or diminish slightly. By contrast, the monetary income of savers-investors will significantly increase, because the PRI does not change whereas the volume of savings strongly increases.

Real revenues will strongly increase in the aggregate. For savers-investors this implies that their real revenues will strongly increase. The owners of original factors, too, will experience a significant increase of their real incomes, for the same reasons we have spelled out in discussing Scenario I.

The present scenario is only slightly behind the first one in its positive implications for growth. (We have to keep in mind that it involves a much stronger increase of the gross savings rate than in Scenario I.) The main difference between the first two scenarios concerns their impact on the distribution of revenues. Scenario I is more favourable for income derived from original-factor ownership than for income derived from saving-investment – though both types of income increase in real terms – whereas in the present scenario it is the other way round.

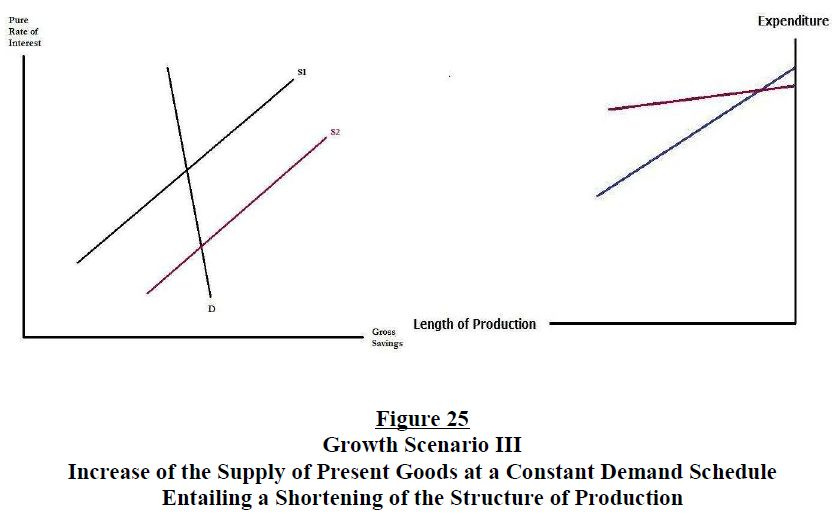

Growth Scenario III

Our third growth scenario is a variant of the first one. Like the latter, it is characterised by an increase of the gross savings rate at a constant demand for present goods, and by a drop of the PRI. However, this time there occurs no lengthening of the structure of production, because the drop of the PRI overcompensates the increase of the gross savings rate. … Consider again our above numerical example. Compare the initial spending stream (Table 2) with the spending stream that we considered as a counterexample (Table 4):

159―138―120―104―90 158―154―151―148

Figure 25 gives a graphical illustration of the corresponding changes on the time market and within the production structure.

[...] The old structure is lengthier, and on that account it is more physically productive than the new one. However, in the new one, spending in the second and third stages (as compared to the consumer-goods stage) is relatively higher than in the first structure. In this case too, therefore, more activity will be shifted from the consumer-good industries to stages of production upstream, and on that account, the new structure is more physically productive than the first one. Finally, the gross savings rate is marginally higher in the new structure, which is therefore more physically productive on that account too. We estimate that this is the 3rd most growth-friendly variation of the time market and the production structure.

The impact of this scenario on the distribution of monetary and real revenues is analogous to the first one. The level of monetary revenues will tend to be higher than in Scenario I because growth is less intense and there is therefore less pressure on prices. However, because the tendency for the economy to grow is less clear-cut than in the first scenario, the level of real revenues will also tend to be less elevated. [...]

The most striking feature of the present scenario is its similarity to the first one. In both case, the initial causal change is an increase of the supply of present goods (savings) on the time market. But depending on the demand for present goods (the “price-elasticity” of demand), the repercussions on the time structure of production and the impact on growth are very different. The bottom-line is that a plummeting PRI, when resulting from an inelastic demand for savings, does not necessarily make for vigorous growth.

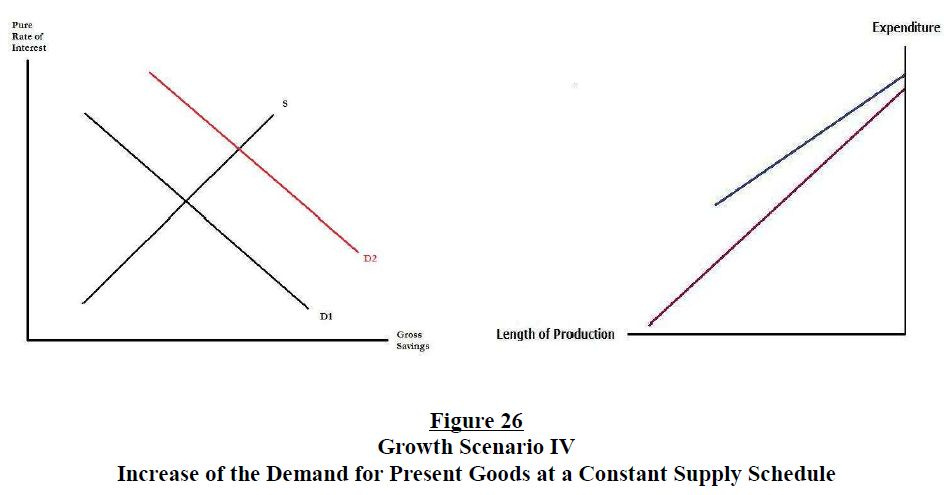

Growth Scenario IV

We have just seen that one and the same initial change of inter-temporal values, reflected in an increase of savings at a constant demand for savings, can give rise to two very different growth scenarios. Similarly, the following growth scenario is one out of two that spring from the same initial change, namely from an increase of the demand for present goods at a constant supply of present goods. On the time market, this implies a new final equilibrium at a higher PRI and a higher gross savings rate. The structure of production lengthens, but at the same time it thins out at the higher stages, with the only exception of the new stages that are being created upstream (Figure 26).

The new structure becomes increasingly thinner toward the upstream, except for the very highest stages, and on that account is less physically productive than the [old] one. However, the new structure is also lengthier and on that account more physically productive than the old one. Last but not least, the gross savings rate is higher in the new structure, which is therefore more physically productive on that account too. We estimate that this variation of the time market and the production structure is on a par with Scenario III and falls therefore within the 3rd highest growth rank. As in Scenario III, there are here two growth mechanisms at work: the lengthening of the structure of production, and the increase of the gross savings rate; and as in Scenario III, one of the growth mechanisms is deteriorating.

The striking difference between the present scenario and Scenario II is that, in the latter case, the PRI drops, whereas here it increases. However, we hold that this difference has a systematic impact, not on growth, but on distribution only.

As far as monetary revenues are concerned, the general tendency is for them to fall because the growth deflation. The monetary income of the owners of original factors of production will have a clear tendency to fall (a) because spending drops in all stages, except for the new stages that are being created upstream; and (b) because a rising PRI means that the marginal value product of the original factors will be discounted more than before. By distinct contrast, the monetary income of savers-investors will significantly increase, because both the PRI and the volume of savings strongly increase. Scenario IV therefore implies a significant reshuffling of the relative weight of income sources. Income from factor ownership will significantly decrease relative to income from saving-investment.

Real revenues will increase in the aggregate. For savers-investors this implies that their real revenues will very strongly increase. For the owners of original factors, the situation is more ambiguous because the increase of interest rates implies a stronger discount of their marginal physical product, which could completely offset the expected increase of that marginal physical product.

The present scenario is ranked on the same level of growth friendliness as Scenario III. The essential difference between these two scenarios concerns their impact on the relative weight of income types. Scenario III is more favourable for income derived from original-factor ownership than for income derived from saving-investment, whereas in the present scenario it is the other way round.

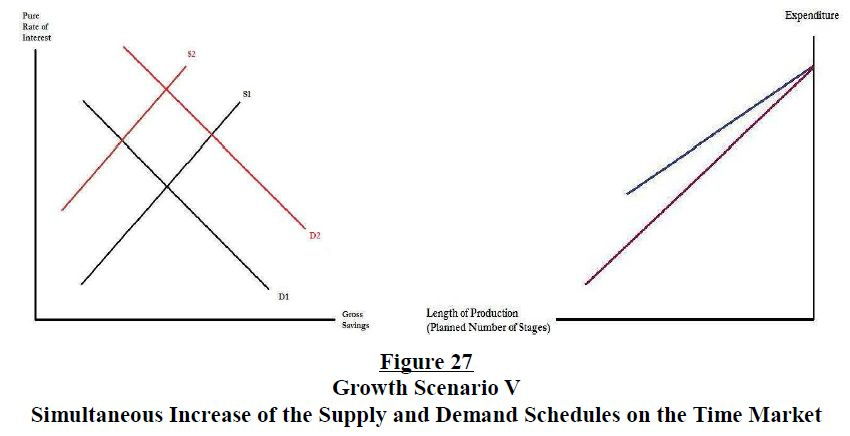

Growth Scenario V

The third growth scenario is characterised by a decrease of the supply schedule and a simultaneous increase of the demand schedule on the time market.

These changes have no systematic impact on the gross savings rate. The PRI is substantially higher in the new structure, which implies a lengthening of the structure of production. The latter therefore becomes more physically productive on that account. However, the same circumstance also exercises an adverse effect, as relative spending diminishes toward the upstream, with the only exception of the new stages. In Scenario V, only the lengthening of the structure of production is here favourable for growth, whereas the gross savings rate stays put, and the relative spending (except for the new stages upstream) deteriorates as far as the prospects for growth are concerned. We rank this scenario below all other scenarios that we have so far considered (4th rank). Indeed, it has no systematic tendency to entail economic growth. It will have this consequence only accidentally, namely, if the advantage of the lengthening more than offsets the disadvantage of the deteriorating relative spending.

As far as monetary revenues are concerned, the general tendency is for them to remain stable, because of the lacking growth dynamics (no growth deflation) and because consumer spending remains stable too. However, the strong rise of the PRI will have a significant impact on the relative weight of the different income classes. The monetary income of the owners of original factors of production will fall because a rising PRI means that the marginal value product of the original factors will be discounted more than before. By distinct contrast, the monetary income of savers-investors will increase, because the PRI [increases] while the volume of savings stays put.

Real revenues will by and large remain stable in the aggregate. The real income of savers-investors will increase. The income from original factor ownership will diminish, because the increase of interest rates implies a stronger discount of their marginal physical product, while there is no significant increase – if any – of the marginal physical product itself.

Growth Scenario VI

The sixth scenario is the exact opposite of Scenario V. It is characterised by an increase of the supply schedule and a simultaneous decrease of the demand schedule on the time market. Thus we can illustrate it with the above Figure 27, which only needs to be read backwards, with the red demand and supply schedules representing the initial situation, and the dark schedules representing the new final equilibrium.

As in Scenario V, the changes we are considering now have no systematic impact on the gross savings rate. The PRI is now substantially lower in the new structure, implying a shortening of the structure of production, which therefore becomes less physically productive on that account. However, the drop of the PRI also tends to promote relative spending upstream, with the exception of the stages that disappear. In Scenario VI, only the reshuffling of relative spending toward the upstream (except for the stages that disappear) is favourable for growth, whereas the gross savings rate stays put, and the structure of production shortens. It therefore has no systematic tendency to entail economic growth. We therefore rank it in category 4.

The impact of Scenario VI on monetary and real revenues is exactly analogous to the one of Scenario V. Thus its distributional consequences are the exact inverse of those that we found in that former scenario. [...]

Growth Scenario VII

Scenario VII is the exact opposite of the above Scenario IV. It is characterised by a decrease of the demand for present goods at a constant supply of present goods. On the time market, this implies a new final equilibrium at a lower PRI and a lower gross savings rate. The structure of production shortens, but at the same time it becomes wider in the higher stages, with the exception of the stages that disappear. We can illustrate Scenario VII with the above Figure 26, which only needs to be read backwards, with the red demand and supply schedules representing the initial situation, and the dark schedules representing the new final equilibrium.

As the new structure becomes increasingly wider toward the upstream, except for the highest stages, it is on that account more physically productive than the new old. However, the new structure is also shorter and its gross savings rate is lower. Thus, Scenario VII features only one basic mechanism promoting growth, whereas the other two basic mechanisms entail the opposite tendency. It therefore seems to be barely justified to speak of a “growth” scenario at all. However, we cannot exclude on purely theoretical grounds that the one positive mechanism overcompensates the two others. This has to be determined empirically for each individual setting. In any case, this is the least probable of all growth scenarios that we have considered. We therefore rank it in a 5th category.

The impact of Scenario VII on monetary and real revenues is exactly analogous to the one of Scenario IV. Thus its distributional consequences are the exact inverse of those that we found in that former scenario. [...]

Growth Scenario VIII

Our last scenario is the exact opposite of the above Scenario III. It is characterised by a decrease of the supply of present goods at a constant and inelastic demand schedule, resulting in a lengthening of the structure of production. On the time market, this implies a new final equilibrium at a higher PRI and a lower gross savings rate. The structure of production lengthens, but at the same time it becomes thinner in the higher stages, with the exception of the new stages. We can illustrate Scenario VIII with the above Figure 25, which needs to be read backwards, with the red demand and supply schedules representing the initial situation, and the dark schedules representing the new final equilibrium.

Just as in the preceding case of Scenario VII, the present growth scenario features only one basic mechanism promoting growth, whereas the other two basic mechanisms entail the opposite tendency. We therefore rank it in the same 5th category in which we have classed Scenario VII.

The impact of Scenario VII on monetary and real revenues is exactly analogous to the one of Scenario III. Thus its distributional consequences are the exact inverse of those that we found in that former scenario. [...]

We shall now turn to consider two complications, by dropping previous assumptions, namely (1) the assumption that the economy operates without consumer credit and (2) the assumption that monetary conditions remain stable.

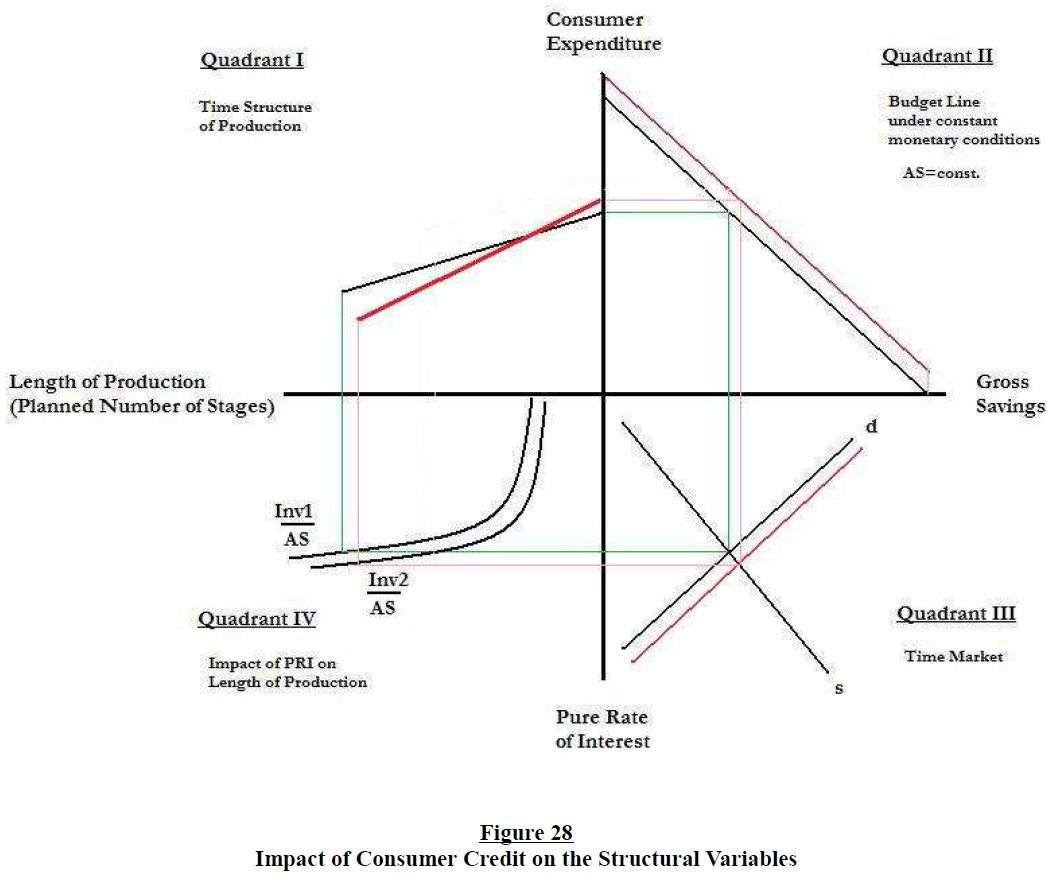

Consumer Credit

Consumer credit transfers a part of the available gross savings to consumers. Aggregate investment spending diminishes while consumer spending increases. The impact of consumer credit on the structure of production can be illustrated with Figure 28. Notice that the accounting identity between savings and investments, which resulted from our previous hypothesis, no longer exists. In our representation of the interdependence of the structural variables, we account for this by shifting the budget line upward.

Because credit is being granted on a competitive basis, the consumer-credit-induced demand for present goods tends corresponds to a right-shift of the demand schedule on the time market. As a consequence, the PRI and the volume of gross savings will tend to increase. This implies a thinning out of the structure of production in the higher stages, along with a simultaneous lengthening. However, the lengthening might be offset or even overcompensated by the simultaneous reduction of investment expenditure.

Thus we see that consumer credit has certain consequences that are similar to our growth Scenario IV (increase of the demand for present goods at a constant supply schedule). However, the important difference is that the volume of savings available for investment drops. An economy with increasing consumer credit features one single growth mechanism – and even this one only under the most favourable circumstances – namely, the lengthening of the structure. By contrast, the other two basic growth mechanisms have turned negative. In other words, consumer credit does nothing for economic growth. Quite to the contrary, it tends to shrink the productive potential of the economy as a whole – just as common sense would suggest.

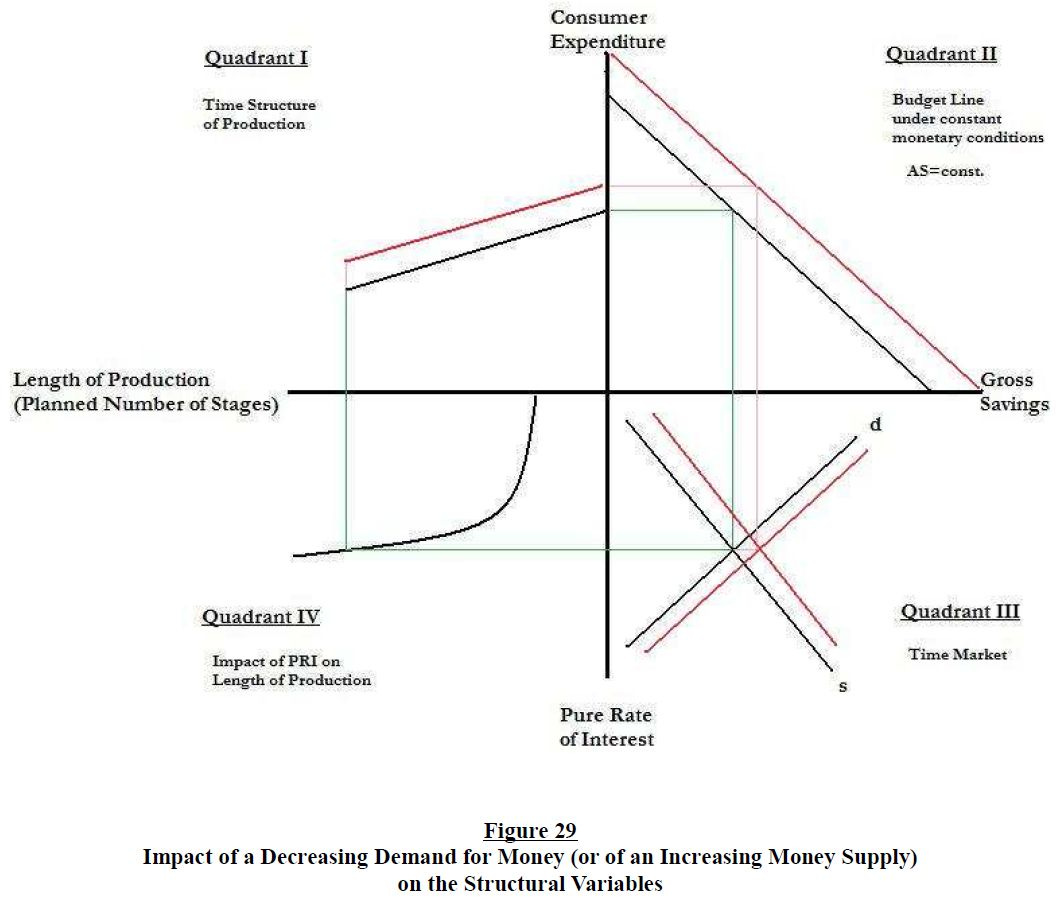

Monetary Variations

So far we have assumed that monetary conditions remain stable throughout each transformation of the structure of production from the initial final equilibrium to the new one. This assumption is of the greatest pedagogical value, as it allows us to disentangle the analysis of the relations between the structural variables from monetary considerations. But it is also a heroic assumption that threatens to invalidate the entire analysis, because money is not just a neutral veil layered over the economy. Rather, money is part of the real economy, and any change in the demand for money or in the money supply affects the distribution of revenues and therefore also the structure of production.

However, from the Austrian point of view, these money-induced structural do not necessarily show up in the aggregate. In line with classical economics, the Austrians hold that variations in monetary conditions do not have any systematic impact on the structure of production. A change in the demand for money will affect relative spending and relative revenues, but there is no way to tell the implications of these changes for the time market and for the structure of production. Let us illustrate such a case in Figure 29. It represents an increase in aggregate spending, which can only result from (a) an increase of the money supply that is not offset by a simultaneous increase of the demand for money, and (b) from a decrease of the demand for money that is not offset by a simultaneous decrease of the money supply. 17

17 Accordingly, a decrease of aggregate spending would result from (a) a decrease of the money supply that is not offset by a simultaneous decrease of the demand for money, and (b) from an increase of the demand for money that is not offset by a simultaneous increase of the money supply. In Figure 29, this would correspond to a movement from the red lines to the black ones.

The increase of aggregate spending is reflected in an outward shift of the budget line. On the time market both the demand for and the supply of present goods (or more precisely, of monetary capital) will increase. The main reason is that the higher spending will sooner or later entail a rise of all monetary revenues. It is therefore possible for capitalists-entrepreneurs to pay higher factor prices and to lend more money, and they will do this under competitive pressure, in order not to lose market shares. Competitive pressure also props up the demand for monetary capital, as capitalist-entrepreneurs line up to benefit from the increase of aggregate spending. It follows that the time market will settle at a new final equilibrium with a greater volume of monetary capital being exchanged.

However, there is no reason to expect any systematic impact on the gross savings rate, and neither is there any reason to expect any systematic impact of these changes on the PRI. Therefore, the key structural variables remain unaffected. The structure of production operates as before (as far as its time structure is concerned), featuring the same relative spending and the same length as before. The only difference from an aggregate point of view is the higher price level, and the corresponding higher level of monetary revenues. Aggregate real revenues remain unaffected, and there is also no impact on the relative weight of the different income sources.

As a result of all that has been said, it should be noted that a decline of the PRI, even without a lengthening of the structure of production can still lead to speculative bubbles and malinvestment. It only requires that spending to be higher in the stages of production further from consumption, not in the stages closest to consumption.

Scenarios 1, 3, 6 and 7 fit this pattern. But recall that there is no impact on growth in scenario 6 and lower growth in scenario 7. Keep in mind that the bubbles grow to enormous proportions, certainly through monetary overexpansion, but also because the economic growth is strong. For “euphoria” to be manifested, everything must increase at the same time, which is possible only if the new money is continually injected into the system (see Fritz Machlup cited in Money, Bank Credit and Economic Cycles, page 462). Without monetary overexpansion, a rise in some prices implies a fall in other prices, all other things being equal, canceling the speculation process. If malinvestments occur, given the fact that scenario 7 implies a less vigorous growth, malinvestments are likely to have less serious impact on the economy (compared to 1929 and 2008, for instance). In addition, scenario 7 does not involve an increased supply of present goods; this poses a theoretical problem because any monetary overexpansion necessarily implies an increase (though illusionary) in the supply of present goods, through a lowering of interest rates. Scenarios 6 and 7 therefore do not contradict the fundamentals of the ABCT.

In scenarios involving an increase of the PRI, we have consistently the same pattern. A lengthening of the structure of production and a thinning of the stages of production further from consumption, the latter necessarily implies that expenditures in stages further from consumption do not increase. In this case, malinvestments cannot arise.

The scenario n°2 shows a curious pattern. The PRI does not drop, but the structure of production lengthens. At first glance, one might think that malinvestment can take place with scenario n°2. Given the fact that ABCT hypothesized that “artificially low interest rates through monetary overexpansion will trigger malinvestments” the core of the ABCT seems to be weakened. Nevertheless, we can reformulate the theory of ABC as follows : “monetary overexpansion will trigger malinvestments” (whether the interest rate drops or remains constant). Therefore, the finding that interest rate is not necessarily inversely correlated with the length of the production structure is still in line with the fundamentals of the Austrian Business Cycle Theory.

Further reading: