The economic discourse has often compared the evolution of economic outcomes of the interventionist Singapore and the market capitalist Hong Kong since the 2nd half of the 20th century. Both portrayals are inaccurate, as they are both hybrid models combining state and market elements. The Economic Freedom Index (EFI) measures failed to detect the subtle mixture state models adopted by East Asian countries. The state of the research so far indicates that state capitalist policies did not improve economic outcomes. Instead, there is some indication that state intervention may have crowded out private business and innovation.

SECTIONS:

1. The myth that Singapore is free. The myth that Hong Kong is free?

2. Why EFI mismeasures the East Asian capitalist systems.

3. The problem of rent-seeking under state capitalism.

5. The questions that need to be asked.

There is a large body of econometric studies establishing a causal negative impact of public spending on private investment in West economies (Kim & Nguyen, 2020; Ünsal, 2020). This is called crowding out effect. There are some evidence of crowding out effects due to government spending/debt in China (Liang et al., 2017), Taiwan (Ho & Chien-Chung, 2002), and South East Asian countries (Bende-Nabende & Slater, 2003). But obviously, it would be too easy if econometrics did not also produce some conflicting results. It was found that expansionary government expenditures and contractionary government revenues both showed heterogeneous effect (most coefficients did not reach significance) on either output, private consumption or private investment in the long run across 10 Asian countries (Hur et al., 2014, Tables 5-6). The general discourse about East Asian countries is that the Asian miracle has something to do with government intervention, materialized as state capitalism or developmental state, the purpose of which is to divert (more) resources toward what appears to be promising industrial sectors (in line with the infant industry argument). Krugman once argued that Singapore’s miracle was due to growth in inputs, which is subject to diminishing returns, rather than growth in efficiency. This view has been validated, as labor productivity growth fell due to slowdown in capital deepening (Lim, 2016, pp. 151-152).

1. The myth that Singapore is free. The myth that Hong Kong is free?

Singapore has achieved exceptional economic growth, averaging 8.25% per year in 1960-1991 despite or due to its tight control and directive role over resource allocation. Repressive measures are justified on the basis of promoting growth, which include a Bill rendering strikes as illegal and the extension of the working week and the reduction in annual and medical leave to increase capital accumulation (Liow, 2012). Singapore exercises extensive control over the allocation of labour and identifies the future needs of the economy, usually targeting STEM. The government provides generous scholarships (i.e., financial aid) to university students in return for employment in government-linked companies (GLCs), and firms in selected industries are given incentives to train workers on specific skillsets pre-identified by the state (Cheang & Lim, 2023). The effectiveness of this targeting may explain why Singapore was able to minimize mismatch between skill demand and supply, as opposed to Sri Lanka’s free education system that has experienced a great expansion mainly in non-technical areas like humanities and social sciences, leading to high unemployment among educated youth (Abeysinghe, 2015). Singapore also employed a policy of compulsory savings deposited to the social security scheme (the CPF) in order to provide the government with more money to invest in infrastructure and housing sector (Siddiqui, 2016, p. 168). Partial crowding out existed though, as Toh (2001, p. 204) calculated that every extra dollar of compulsory saving reduces voluntary saving by about 55 cents, all else constant.

The requirement for attracting foreign investors is a conducive environment, including a good infrastructure, minimum uncertainties with respect to the repatriation of profits, foreign exchange risk, business legislation, and political conditions, which is why Singapore adopted a market-friendly stance and immediately started to remove trade barriers soon after gaining independence in 1965 (Lim, 2016, p. 58; Toh, 2001). Due to running frequent budget surpluses, there was no need to use debt to finance spending (Peng & Phang, 2018). Interestingly, Singapore did not impose a minimum wage (Peng & Phang, 2018).

On the other hand, the view that the government involvement helped shape Singapore is misguided. It has been observed that government-linked companies (GLCs) played a strategic role in Singapore’s development. This is puzzling because such state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in China often crowd out private business due to their privileges, as is the case in Vietnam (Van Thang & Freeman, 2009), Malaysia (Menon & Ng, 2017), and Ukraine (Cevik, 2020). In reality, these GLCs in Singapore did not enjoy such privileges and therefore performed similarly compared to privately run enterprises (Feng et al., 2004; Ramirez & Tan, 2004). It was observed that GLCs have higher firm value than non-GLCs (Ramirez & Tan, 2004; Ang & Ding, 2006), which has been wrongly attributed to better governance (Ang & Ding, 2006). In the latter study, the higher valuation of GLCs was established while controlling for profitability and governance measures. There are two other interpretations for the higher firm valuation: one is brand recognition due to the company being linked to the government and the other is the belief that the government will bail out that company in case of bankruptcy (Ramirez & Tan, 2004). In this case, the higher valuation of GLCs cannot be interpreted as necessarily a good thing or a market failure. Indeed, it has been established that both the lower level of government involvement and higher qualification of board members (governance) could explain why GLCs in Singapore outperform GLCs in Malaysia (Khai, 2023).

The common view that Hong Kong is the last bastion of (almost) unfettered capitalism is inaccurate. HK is not an exception, having embraced state capitalism just like the other East Asian countries. Cheung (2000) said that HK adopted price controls in order to promote exportations along with social wage subsidies to reduce the larger cost of living caused by this export-led growth scheme. Cheung (2000) also informed us that, between 1949 and 1984, the HK government capital formation expanded by 16.7% annually and government capital formation as a percentage of GDP rose from 1.6 to 5.0%, while government expenditure on education and healthcare expanded by 18.7 and 16.8% annually. Lam (2000) reported that the state was controlling land supply and providing public housing, but its tight control over land supply has been criticized for inflating land value. There were also price controls on many food items, subsidies for medical services, regulation of public transport and utility industries, tightening of bank supervision. Non-intervention was only obtained at the micro-level of market operations.

In some respects, and ignoring nitpicks, Hong Kong can be regarded as remarkably free. Its economic development can be attributed to adaptive entrepreneurship, which involves being flexible and alert to opportunities, especially for small firms (Yu, 1998). The government had only very limited capacity to support the development of strategic industries, its involvement was very limited overall even in the financial market (Tsui‐Auch, 1998). The best illustration comes from its banking system (Schenk, 2018, p. 82), which had no central bank and its paper currency was issued by two private competitive banks (Rossiter, 1994). This is quite remarkable given that this time period (1935-1964) corresponds to the hegemony of central banking and the complete ban of free banking everywhere else in the world. This quasi-free banking system with no reserve ratio requirement until 1964 was exempt from bank runs, except one due to the government’s involvement.

In the aftermath of the 1997 Asian crisis, Singapore questioned the viability of their developmental state and decided to implement policies aimed at deregulating the economy, which affected the banking, services, telecommunications, healthcare, public transport and power sectors (Liow, 2012). And even the de-linking of government-linked companies (GLCs) from the government has been undertaken, despite the fact that the GLCs maintained close ties with the state (Liow, 2012), along with the transfer of SGD 62 billions from the Central Provident Fund (CPF) owned by the government to private fund managers (Robison et al., 2005).

In 1997, Hong Kong reunified with China, causing fear and anxiety at first. This did not play a role in the economic downturn following 1997 (So, 2011). But interventionism was obvious. The government tried to simulate the economy through new public spending and rates rebates and credit insurance scheme to help small-medium enterprises (SMEs), freezed the sale of land to control its current price, and substantially purchased stocks to counter so-called speculative attacks (Cheung, 2000, p. 306; Lam, 2000, Table 4; Lim, 1999, pp. 104-106). The most interesting figure is that the cost of Hong Kong’s economic revival plan was 4.5 times that of its Singapore counterpart despite using very similar economic plans (Lam, 2000).

There is suggestive evidence that HK’s growth slowed after China took over in 1997. Groenewold & Tang (2007) employed autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) and Granger causality tests to examine the long-run relationship between democratic accountability and GDP growth from 1984 to 2003. ARDL established the existence of such a long-run relationship, whereas Granger established the existence of a unilateral causality running from democratic accountability to GDP growth.

2. Why EFI mismeasures the East Asian capitalist systems.

Why would the Economic Freedom Index (EFI) give a very high rating for Hong Kong and Singapore? Cheang & Lim (2023) argue that EFI is only useful when the research purpose is to discover large-N relationships between freedom and a range of welfare indicators. The construction of the EFI variable conceals important configurations of market institutions, which causes strong bias in some other types of analysis. Capitalism can be structurally dissimilar owing to institutions exhibiting varying, complex forms. The EFI ignores contexts, unique combination of state and market elements that work best in their own contexts. Capitalism is already treated as the norm in most countries, therefore treating capitalism as a continuum and ranking countries based on this continuum makes little sense. A variable measuring “interventionist mentality” has been introduced in the EFI, but institutions are embedded in specific social-cultural-historical contexts, resulting in divergent forms of capitalism which complicate comparison and aggregation. The divergent clusters that arise exhibit their own sources of comparative advantage. This qualitative difference implies that aggregation is not viable. Two countries can achieve the same EFI scores even if one adheres to a more collectivist form of capitalism. The reason EFI fails to make this distinction is because it adopts the old view that opposes socialism and capitalism, but now the modern economic discourse is about varieties of capitalism. Government expenditure may be comparatively small, and yet government control over the economy close if there are many state trading monopolies, or if there is extensive licensing of economic activity.

Cheang & Lim (2023) illustrates how Singapore managed to “fool” the EFI variable. Despite the state being lean in size, it achieved outsized influence over economic processes. Singapore determines land distribution for various uses and has extensive control over land. Historically, this has included forced relocations and the displacement of families. Ironically, Singapore violates private property rights despite ranking very high on EFI’s index of property rights protections. Despite its low tax and low spending reputation, the state controls the direction of capital flows by providing favourable loans and direct cash grants for eligible small-medium enterprises (SMEs). The state indirectly owns many firms (which are private entities on de jure basis) but this is not seen in the EFI index “state ownership of the economy” because the question is about direct ownership. Government-linked entities indeed constitute a large share of the stock market capitalisation.

3. The problem of rent-seeking under state capitalism.

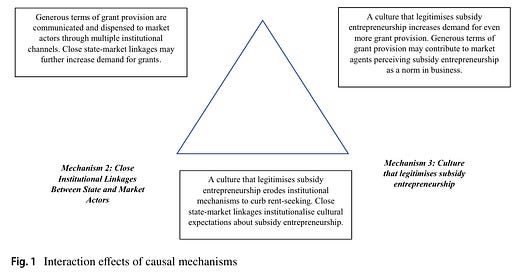

Cheang (2023) explores how rent-seeking behaviours have been legitimized due to the pernicious incentives created by the Singaporean state. Rent-seeking activities divert resources, resulting in a loss of economic welfare and efficiency. Certainly, culture and institutions interact with each other. If a nation’s formal rules and culture both sanction rent-seeking, their synergistic effects reinforce each other. If corruption is baked into the fabric of regular life, institutional efforts to control corruption could fail. Yet, a rent-seeking culture may arise from the vision of the developmental state. Instead of restricting the private sector, developmental states focus on pro-business interventions that support firms. This can take the form of industrial subsidies (transfer payments) or tax breaks, cash grants, favourable loans, partnerships, and joint ventures. The generous terms of grant provision create strong incentives for subsidy entrepreneurship (those who seek rents) and for grant recipients to expend resources to surmount the many performance checks imposed by the state.

But of course, measures are undertaken to maximize good incentives. Companies that complete government funded projects are featured as model success stories on state-owned public media. The evaluation of firms’ suitability for government support is based on careful screening, e.g., business performance, inspections etc. Yet “subsidy entrepreneurs” (a by-product of rent-seeking) typically present themselves as consultants dedicated to “advising” companies on how best to secure and maximize grants, rather than long-term technology upgrading. The government agency admitted that these so-called consultants have misled many workers to make false claims to get cash pay-outs, resulting in $358 million worth of fraudulent claims in 2016 that were not recovered. It is indeed difficult for officials to screen effectively. There are too many grant recipients for careful checks to be done. In a context where securing grants is baked into the usual practice of business, it is difficult to distinguish between firms who are genuine in using a grant for its intended purpose, or those who simply obtain it as a source of easy cash.

Cheang (2023) conducted an online survey, one focus group discussion, and a series of interviews. The result is rather telling. Former employees of Enterprise Singapore recounted the challenge of accurately distinguishing deserving recipients from those who were good at “crafting a nice story”. One focus group participant articulated how some firms would only engage in software investments if the costs were covered by grants. A venture capitalist founder in Singapore admitted that a good number of local entrepreneurs often consider government grants as much as they do private financing. Some administrators in trade associations recounted some cases of firms applying for grants simply as means of acquiring quick resources, betraying the intent of the grants’ aim to encourage long-term productivity. All in all, the crutch mentality exists.

There are two consequences of a rent-seeking culture: it conceals unproductive entrepreneurship and fosters a dependency mindset that distorts the judgement of entrepreneurs. The latter is of utmost importance because the firms now feel unable to sustain their operations in the absence of subsidies. Indeed, Singaporean youths are the least inclined to entrepreneurship as compared to six other Asian countries, and most of the gains from innovation in Singapore are captured by the foreign and state sectors rather than local enterprises. Despite Japan, Hong Kong, China, and New Zealand having a lower level of creative inputs than Singapore, they achieve a higher level of creative output because Singapore is less effective at turning creative inputs into outputs. This is further confirmed by Singapore’s low ratings in perceived skills and opportunities as well as start-up success (Cheang, 2024) and bad rank in the INSEAD innovation ranking (Lim, 2016, p. 73). Singapore has not developed a strong local enterprises due to lack of incentive in an economy dominated by the state and multinational companies (Lim, 2016, p. 162), which could help explain the low growth in productivity between 1974 and 2011 despite multiple productivity-boosting policies (Lim, 2016, pp. 150-151).

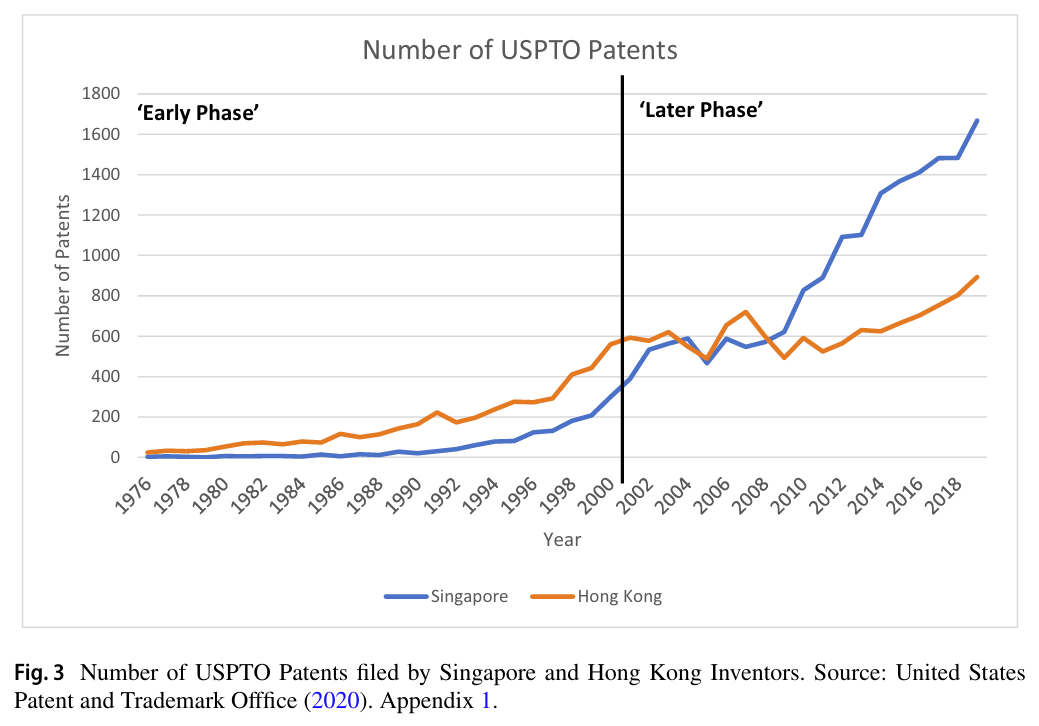

Cheang (2024) shows that Hong Kong’s TFP was consistently greater than Singapore between 1964 and 1997. If industrial policy is successful, we should have expected Singapore to surpass HK. The evolution of patents (a proxy for innovation) over time shows that HK surpasses Singapore until the early 2000s when a structural break happened, and Singapore started to eclipse HK seemingly due to taking more pro-market policies. The higher figures post-2000 for Singapore are misleading because 80% of all private sector patents in Singapore applied for were by foreign entities rather than domestic ones.

Cheang (2024) rightfully argued that the turning point is likely HK’s 1997 handover, as it abandoned its laissez-faire in trying to emulate Singapore’s early industrial, interventionist policies. However, the importance of democratic accountability is probably not negligible (Groenewold & Tang, 2007).

Audretsch & Fiedler (2023) argue that the entrepreneurial state distorts funding opportunities for SMEs, because strategic support for the selected targeted industries renders funding in areas outside the state’s innovation strategy riskier. The share of business credit allocated to SMEs lagged considerably behind other East Asian economies. All six Singaporean unicorns (i.e., startup company valued at over US$1 billion) are either founded or co-founded by foreign entrepreneurs. In Singapore, entrepreneurship is stigmatized by a lower social status than in other Asia-Pacific countries. Singaporean private investors, including venture capitalists, are more likely to invest in startups that have participated in a government support scheme.

4. Econometric studies

If the export-led growth model employed by public policies in both Singapore and Hong Kong is effective, exports must cause GDP. Tang et al. (2015) examine the causal relationship between GDP and exports for the Four Little Tigers (Hong Kong 1973-2007, South Korea 1960-2007, Singapore 1966-2007, Taiwan 1961-2007) using MWALD causality test. Regardless of whether the bivariate model (exports and GDP) or trivariate model (exports, GDP and exchange rate) is used, the results indicate that exports Granger-cause GDP and vice versa for Hong Kong and Singapore, while there is only unilateral causality running from GDP to exports for South Korea and Taiwan. They also found evidence of cointegration, which implies that there is at least uni-directional causality. In order to investigate whether the causal relationship is stable over time, they incorporate the rolling regression procedure into the MWALD causality test. They found that this causal relationship is unstable (due to a variety of reasons such as external factors) which explains why earlier studies (including this one) produced mixed results. Tang (2013) applied the same statistical procedures for Malaysia and provided evidence of a bilateral causality but also found that this causal relationship is unstable over time, further emphasizing why the empirical tests often produce conflicting results. Mahadevan (2009) mentioned several methodological issues in past studies of causality tests, which could be another explanation for these conflicting findings. In any case, the lack of evidence of positive effect is important here because both Singapore and Hong Kong forced the expansion of their exportations.

Ho & Wong (2017) analyze the impact of R&D on economic performance for Singapore from 1978 to 2012 while Wong et al. (2023) updated the analysis for the 1978-2019 period. Both analyses employ the Granger causality test and showed that public sector R&D expenditure stimulate R&D activities in the private sector but not vice versa. The assumption of the stability (i.e., no structural break) in the relationship between R&D capital stock and productivity (i.e., TFP) was validated by the Chow Test. The long-run elasticity of TFP to changes in R&D capital for Singapore is far lower than for the OECD countries, indicating lower R&D productivity which could be due to the nature of the R&D in Singapore. At first glance, these results give support to the state capitalism. However, considering we have learned before that the state conditioned the Singaporean youths to depend on the state to lead their businesses, it is no wonder why public R&D would boost private R&D by driving up expectation of economic agents, only in Singapore, but not in other East Asian economies. Another issue is the magnitude of effect. Both studies employed a short-run Error Correction Model with lagged values of TFP and log of R&D predicting TFP, and both revealed a small log coefficient for R&D (0.022 and 0.025) considering the observed TFP values displayed in their Figures, ranging between 1.3 and 1.8.

Following Ho & Wong (2017) approach, Sharif et al. (2021, Tables 7-8) employed Granger causality test but compared Singapore (1981-2017), Shenzhen (2001-2017) and Hong Kong (1998-2017). They found evidence of unilateral causality running from public R&D to private R&D for Hong Kong, bilateral causality between public and private R&D for Singapore, but no causality at all for Shenzhen. It is not clear why public R&D boosts private R&D for Hong Kong. Based on Kernel regression, with lagged TFP and R&D both predicting TFP, they found that private R&D (but not public R&D) is related to TFP growth in Hong Kong, while both private and public R&D are related to TFP growth in Singapore. The coefficient for Singapore is rather small but it is difficult to assess its magnitude without knowing the baseline value of the TFP. Given the TFP values displayed in their Figure 5, varying between 1.65 and 1.85, a coefficient of 0.035 (in log estimate) for both private and public R&D is indeed quite small. Yet the authors conclude there is an important, significant effect in the case of Singapore. The main problem of econometricians is that they always rely on significance tests to establish relationship and causality, and they often have little regard with the magnitude of effects.

Wang (2018) compared the relationship over time between innovation (based on either patent citations or IPC count) and local firms for Singapore and Hong Kong. Three periods are analyzed: 1980-1991 (phase 1), 1992-2006 (phase 2), 2007-2013 (phase 3). The rationale for this comparison is that Hong Kong is the ideal counterfactual (which in fact isn’t), allowing therefore one to evaluate whether interventionism is more effective than laissez-faire at boosting innovation. A crucial question because Singapore introduced various policy instruments targeting only local firms since the 1990s. Based on a difference-in-differences (DiD) analysis, using local companies as the treatment group and foreign companies as the control group as well as fixed effects of years and technology fields, it is found that local industries in Singapore are growing faster than the foreign counterparts but this is only obvious in phase 3 (2007-2013) while the local industries in Hong Kong are not improving relatively to their foreign counterparts in patent citations or falling behind in IPC4 count on either phase 2 or 3. The coefficients for Singapore are also larger than HK.

One crucial assumption of DiD analysis is the equality of group (control vs treatment) differences over time, but this assumption has not been thoroughly tested for the reference time phase and the time phases chosen are arbitrary and could have undergone sensitivity tests through different time period ranges. Given Figure 3 in Cheang (2024) displayed in Section 3, the huge breakdown in the aggregate trends in patents since the early 2000s is concerning. Because that breakdown marks the departure in economic policies and institutional environment between Hong Kong and Singapore (becoming omitted variables), as seen in Section 1, the validity of the DiD test is questionable since there is no adjustment for these external factors. Even if all equality assumptions are tenable, the author did not propose any causal mechanism, e.g., how the increase in patent citations since the 2000s is linked to a specific R&D policy. This is concerning because the improvement in patent citations in phase 3 is much stronger than phase 2, but there is no evidence this is linked to specific R&D policies.

5. The questions that need to be asked.

There is ample evidence that government intervention crowds out private businesses (Kim & Nguyen, 2020; Ünsal, 2020). Even in the case of East Asian countries, such as China, that embrace state capitalism, this economic rule seems to apply. Although once again, econometrics wouldn’t be econometrics without its conflicting results (Hur et al., 2014; Mohanty, 2018; Ünsal, 2020). There are many reasons, one of which could be due to the components of public expenditure having varying and opposite effects on private investments, either crowding out or crowding in (Serin & Demir, 2023). Yet replication crisis often happens and is not surprising, especially in economics (Chang & Li, 2015). A question one must ask is whether the outcome would improve if the state did not intervene. Even if Hong Kong is not an acceptable counterfactual for Singapore, the literature suggests that the state doesn’t improve economic outcomes. This is not surprising at all considering that the infant industry theory, one of the argument for strong government support in developing countries, received mixed support. This is a major problem with many papers that employ econometric techniques. Quite often, these researchers do not have or do not propose a better alternative theory for the superiority of the government intervention over market adjustment. Even if econometrics support interventionism, they still have to come up with a theory of state capitalism that is equally valid, if not more, than the free market counterpart. And if econometrics still fail to reach common grounds, there is no reason to either reject or revise classical economic theories on the matter.

As observed earlier, Singapore liberated its economy after the 1997 Asian crisis. An interesting observation is that Singapore handled the crisis very well, and better than other Asian countries in the region. Market liberalization is a good explanation and is fully consistent with the evidence that economic freedom mitigates recessions. Furthermore, Ngiam (2000) observed that, after 1985, Singapore’s National Wages Council (NWC) implemented a non-mandatory wage guideline which consists in a fixed basic wage and a monthly variable component along with measures aimed at reducing business costs and the adoption of a flexible exchange rate to avoid speculative attacks against the Singapore dollar. The general approach of these policies is not hostile to market capitalism, quite the contrary. Some measures were not market-oriented however, such as the stabilization of property prices to prevent bankruptcies and non-performing loans. It is extremely doubtful that such a policy is more effective than market price adjustments.

Generally though, disentangling the observed outcomes and what-would-be outcomes (i.e., counterfactuals) is difficult. As stated above, the East Asian approach to economics is rather complex, as the way their governments influence the allocation of resources is very subtle by combining and mixing market and developmental state strategies. Some dimensions of the government intervention could even be effective in some specific cases. Still, one pattern seems obvious given the current literature: the more advanced the economy, the more likely a strong intervention would cause more damage.

Reference

Abeysinghe, T. (2015). Lessons of Singapore’s Development for other Developing economies. The Singapore Economic Review, 60(03), 1550029.

Ang, J. S., & Ding, D. K. (2006). Government ownership and the performance of government-linked companies: The case of Singapore. Journal of Multinational Financial Management, 16(1), 64–88.

Tsui‐Auch, L. S. (1998). Has the Hong Kong model worked? Industrial policy in retrospect and prospect. Development and Change, 29(1), 55–79.

Audretsch, D. B., & Fiedler, A. (2023). Does the entrepreneurial state crowd out entrepreneurship?. Small Business Economics, 60(2), 573–589.

Bende-Nabende, A., & Slater, J. (2003). Private capital formation: Short-and long-run crowding-in (out) effects in ASEAN, 1971-99. Economics Bulletin, 3(28), 1-16.

Chang, A. C., & Li, P. (2015). Is economics research replicable? Sixty published papers from thirteen journals say ‘usually not’.

Cheang, B. (2023). Subsidy Entrepreneurship and a Culture of Rent-Seeking in Singapore’s Developmental State. Studies in Comparative International Development, 1–31.

Cheang, B. (2024). What can industrial policy do? Evidence from Singapore. The Review of Austrian Economics, 37(1), 1–34.

Cheang, B., & Lim, H. (2023). Institutional diversity and state-led development: Singapore as a unique variety of capitalism. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 67, 182–192.

Cheung, A. B. L. (2000). New Interventionism in the Making: Interpreting state interventions in Hong Kong after the change of sovereignty. Journal of Contemporary China, 9(24), 291–308.

Cevik, S. (2020). You are suffocating me: Firm-level analysis of state-owned enterprises and private investment. Journal of Comparative Economics, 48(2), 292–301.

Feng, F., Sun, Q., & Tong, W. H. (2004). Do government-linked companies underperform?. Journal of Banking & Finance, 28(10), 2461–2492.

Groenewold, N., & Tang, S. H. K. (2007). Killing the goose that lays the golden egg: institutional change and economic growth in Hong Kong. Economic Inquiry, 45(4), 787–799.

Ho, T. W., & Chien-Chung, N. (2002). Crowding-in or crowding-out? Analyzing government investment in Taiwan. The Asia Pacific Journal of Economics & Business, 6(2), 74.

Ho, Y. P., & Wong, P. K. (2017). The impact of R&D on the Singaporean economy. STI Policy Review, 8(1), 1–22.

Hur, S. K., Mallick, S., & Park, D. (2014). Fiscal policy and crowding out in developing Asia. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 32(6), 1117–1132.

Khai, Y. Y. (2023). Comparing Government-linked Companies of Malaysia and Singapore: Governance, Government Involvement, and Economic Performance of Government-linked Companies.

Kim, T., & Nguyen, Q. H. (2020). The effect of public spending on private investment. Review of Finance, 24(2), 415–451.

Lam, N. M. (2000). Government intervention in the economy: a comparative analysis of Singapore and Hong Kong. Public Administration and Development: The International Journal of Management Research and Practice, 20(5), 397–421.

Liang, Y., Shi, K., Wang, L., & Xu, J. (2017). Local government debt and firm leverage: Evidence from China. Asian Economic Policy Review, 12(2), 210–232.

Lim, L. Y. (1999). Free market fancies: Hong Kong, Singapore, and the Asian financial crisis. Pempel, T. J. (Ed.). The politics of the Asian economic crisis (p. 101-15). Cornell University Press.

Lim, L. Y. (2016). Singapore’s economic development: Retrospection and reflections. World Scientific.

Liow, E. D. (2012). The neoliberal-developmental state: Singapore as case study. Critical Sociology, 38(2), 241–264.

Mahadevan, R. (2009). The sustainability of export-led growth: The Singaporean experience. The Journal of Developing Areas, 233–247.

Menon, J., & Ng, T. H. (2017). Do state-owned enterprises crowd out private investment? Firm level evidence from Malaysia. Journal of Southeast Asian Economies, 507–522.

Mohanty, R. K. (2018). Does fiscal deficit crowd out private corporate sector investment in India?. The Singapore Economic Review, 63(1), 1650030.

Ngiam, K. J. (2000), Coping with the Asian Financial Crisis: The Singapore Experience, Visiting Researchers Series, Paper No. 8, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore.

Peng, N., & Phang, S. Y. (2018). Singapore’s economic development: pro-or anti-Washington Consensus?. Economic and Political Studies, 6(1), 30–52.

Ramirez, C. D., & Tan, L. H. (2004). Singapore Inc. versus the private sector: are government-linked companies different?. IMF Staff Papers, 51(3), 510–528.

Robison R., Rodan G and Hewison K (2005) Transplanting the neoliberal state in Southeast Asia. In: Boyd R and Ngo T (eds) Asian States: Beyond the Developmental Perspective. London and New York: Routledge Curzon, pp. 172–98.

Rossiter, R. D. (1994). Free Banking in Hong Kong. International Economic Journal, 8(1), 39–51.

Schenk, C. R. (2018). Hong Kong and Global Finance: The Limits to Free Market Foundations. Monde (s), (1), 67–88.

Sharif, N., Chandra, K., Mansoor, A., & Sinha, K. B. (2021). A comparative analysis of research and development spending and total factor productivity growth in Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Singapore. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 57, 108–120.

Serın, S. C., & Demir, M. (2023). Does Public Debt and Investments Create Crowding-out Effect in Turkey? Evidence from ARDL Approach. Sosyoekonomi, 31(55), 151–172.

Siddiqui, K. (2016). A study of Singapore as a developmental state. Chinese Global Production Networks in ASEAN, 157–188.

So, A. Y. (2011). “One Country, Two Systems” and Hong Kong-China National Integration: A Crisis-Transformation Perspective. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 41(1), 99–116.

Tang, C. F. (2013). A revisitation of the export-led growth hypothesis in Malaysia using the leveraged bootstrap simulation and rolling causality techniques. Journal of Applied Statistics, 40(11), 2332–2340.

Tang, C. F., Lai, Y. W., & Ozturk, I. (2015). How stable is the export-led growth hypothesis? Evidence from Asia’s Four Little Dragons. Economic Modelling, 44, 229–235.

Toh, M. H. (2001). Savings, capital formation, and economic growth in Singapore. Mason, A. (Ed.). Population Change and Economic Development in East Asia: Challenges Met, Opportunities Seized (p. 185–208). Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Ünsal, M. E. (2020). Crowding-out effect: evidence from OECD countries. İstanbul İktisat Dergisi, 70(1), 1–16.

Van Thang, N., & Freeman, N. J. (2009). State-owned enterprises in Vietnam: are they ‘crowding out’ the private sector?. Post-Communist Economies, 21(2), 227–247.

Wang, J. (2018). Innovation and government intervention: A comparison of Singapore and Hong Kong. Research Policy, 47(2), 399–412.

Wong, P. K., Ho, Y. P., & Singh, A. (2023). The Impact of R&D on the Singaporean Economy Over 1978–2019. The Singapore Economic Review, 1–27.

Yu, T. F. L. (1998). Adaptive entrepreneurship and the economic development of Hong Kong. World Development, 26(5), 897–911.