Adoption (IQ) gain of Institutionalized, Deprived Children: Threshold effect, regression, no g

Adoption research reports that adopted children are often deprived of positive experiences prior to adoption. Orphanages, for instance, offer fewer opportunities for children to acquire skills necessary to succeed in school, leading to deficits in cognitive prowess. However, after adoption it was found that adopted children, after leaving the institution, consistently outperformed those left behind in terms of cognitive and achievement outcomes and often catch up to their current (environmental) non-adopted peers or siblings with respect to cognitive abilities (van Ijzendoorn et al., 2005). The disappointing outcome found in meta-analyses of cross-sectional studies is that adoptees often underperformed relative to their non-adopted peers in terms of achievement attainment and displayed learning problems more often (van Ijzendoorn et al., 2005) despite their adoptive parents having above average education levels.

(June 2023 update: Added my transracial adoption study of the HSLS)

Since adoptive parents usually have high SES and are highly motivated parents, it is argued that range of restriction in parenting quality reduces effect sizes, therefore we should not expect large effect sizes.

Knowing this, the following reasons are often given as main factors of achievement lags: learning problems for which special treatment was needed (van Ijzendoorn et al., 2005), autism and inattention/overactivity syndromes (Kumsta et al., 2010) with its effect on cognitive ability (Stevens et al., 2008; Fuglestad et al., 2013), iron deficiency affecting moderately cognitive functions (Fuglestad et al., 2013; Doom et al., 2014, 2015; Hearst et al., 2014). Because most of the adverse psychological outcomes resulting from institutional deprivation appear as early as 6-18 months of age (McCall et al., 2011; Zeanah et al., 2011), i.e., what these researchers typically call sensitive period, McCall et al. (2011) suggest that these deficits may have strong biological basis. One is the stress neurobiology that is said to be the most likely biological factor, and another is the insecure attachment relationship with caregivers that is suspected to be the most powerful source of psychosocial stress (Gunnar & Quevedo, 2007; Loman & Gunnar, 2010).

The study by van Ijzendoorn et al. (2005, Table 3) revealed that age of adoption had inconsistent relationship with IQ, given the reported ds of .014, -0.45 and 0.37 (some ds showed large heterogeneity) for comparison between adopted and nonadopted children aged 0-12 months, 12-24 months, >24 months, respectively. Interestingly, the ds of .009, 0.32 and 0.42 for school achievement indicate that age of adoption had a consistent and linear relationship with school achievement. If age of adoption is a proxy for environmental effect, it suggests this may not be g loaded, due to its positive and consistent behavior on school achievement but not on IQ. While these authors point out that age of adoption could be an important factor determining achievement and cognitive trajectories, such a relationship is pointless if the adoptees did not experience severe adversities prior to adoption (Odenstad et al., 2008; Lindblad et al., 2009). Furthermore, pre-institutional exposure to risk (including prenatal and postnatal events) is often considered as a potential confounder in estimates of the effects of subsequent exposures. However, in many studies children enter institutions soon after birth.

And although stressful conditions are often given as an explanation for the poorer educational outcomes of adopted children relative to their non-adopted peers, it does not always have to. Under stressful environments, children may exhibit hidden talents, or specialized skills, in a way that helps them adapt to harsh environments, given an evolutionary-developmental perspective, compared to those children who did not experience early adversities (Ellis et al., 2020). For instance, stress-adapted people perform better in practical cognitive tasks (likely have nothing to do with cognitive skills) and while they exhibit a deficit in sustaining attention, they are adept at shifting their attention between tasks. Therefore, shifting conventional teaching methods toward ones which leverage attention shifting or these specialized skills, would allow adopted children to better catch up in educational achievement and eventually resolve the well-known problem of adopted children having learning issues such that require special education (van Ijzendoorn et al., 2005).

All of the above discussion however relies on outcome mainly coming from cross-sectional data. Results from longitudinal studies such as the ERA data of Romanian adoptees in England and the CAN data of Chinese adoptees in the Netherlands, contradict this common finding that adoptees achieve complete catch-up in cognitive abilities but not scholastic achievement (Castle et al., 2010; Finet et al., 2019).

The most prominent and over-used longitudinal data is the English and Romanian Adoptees (ERA) Study, along with the Bucharest Early Intervention Project (BEIP). Perhaps quite unsurprisingly, since these Romanian children showed sustained IQ gains at adulthood despite being severely deprived prior to adoption (Sonuga-Barke et al., 2017; Humphreys et al., 2022). Another longitudinal study among the Add Health adolescents showed, on the other hand, that parenting has no lasting impact on verbal IQ at late adolescence (Beaver et al., 2014). Another one comes from the Chinese Adoptees in the Netherlands (CAN), for which it has been found that parenting sensitivity and efficacy did not moderate the association between pre-adoption experiences and children’s cognitive test scores (Finet et al., 2019). Taken together, these studies strongly suggest a threshold effect of environmental variations, as the Add Health adoptees definitely were a lot healthier than the ERA adoptees. The CAN adoptees likely were healthy as well since they were mainly adopted due to China’s birth control policy. However, the authors pointed out that since a significant effect of type of care on intellectual abilities was found the first months after adoption, this contradicts this explanation to some extent. While these findings suggest biological, health-related variables as one explanation of the threshold effect, one must bear in mind that some of these biological (and pre-adoption related) variables are negatively associated with the g factor (Flynn et al., 2014).

Because international adoption was widespread among Western countries, a legitimate question pertaining to adopted child’s adjustment is how differences in country of origin shape important psychosocial variables, such as attachment security. A meta-analysis (van den Dries et al., 2009) found that the type of placement, e.g., domestic or international, same-race or transracial, did not moderate attachment security, which suggests that the discrimination effect is null, and that the changed environment provided by the parents is of more significance. In fact, international adoptees were less often referred to mental health services compared with domestic adoptees (Juffer & van Ijzendoorn, 2005).

What about longitudinal transracial adoption studies? Those are scarce, especially with respect to either cognitive ability or scholastic achievement. The most prominent one was the Minnesota Transracial Study involving Black adoptees, Black-White interracial adoptees, and White adoptees by White families which reported the interracials’ cognitive score being intermediate to Black adoptees and White adoptees at both age 7 and 17 (Weinberg et al., 1992, Table 2). That is, they regressed toward their expected genotypic mean. The hereditarian explanation is the increasing genetic effect of IQ with age, which is why most longitudinal studies are meaningless since they failed to include follow up data to adulthood. The environmental explanation has been the expectancy effect, which was found to be false. This result is generally consistent with my comprehensive review of studies on education programs which typically fail to improve IQ in the long run, and also consistent with research showing that education and adoption gains are not correlated with the g factor (Jensen, 1997; Ritchie et al., 2015; te Nijenhuis et al., 2015; Lasker & Kirkegaard, 2022). The relevance of the studies from Jensen and, later, te Nijenhuis is that some have samples of severely neglected children.

Another advantage of late follow-up in longitudinal studies is the examination of possible sleeper effects which emerge at a much later point in development (Zeanah et al., 2011). In some data, children show a rapid recovery of executive function but when tested at a later age, they may show deficits on aspects of visual processing. This understudied outcome deserves more careful investigation.

What is our conclusion then? Adoption gains may not be g-loaded. Even if they were, threshold effect for environmental variations is expected, and therefore huge gain becomes an invalid argument as to the racial IQ gap.

What is next? More longitudinal studies are needed. Better cognitive tests are needed as well. In many of these adoption studies, the subjects were administered a short version of the full IQ battery (e.g., 2 verbal and 2 performance subtests). Not only that, none of these studies, except Ritchie et al. (2015) and Lasker & Kirkegaard (2022), attempted to model g in a longitudinal fashion.

Update

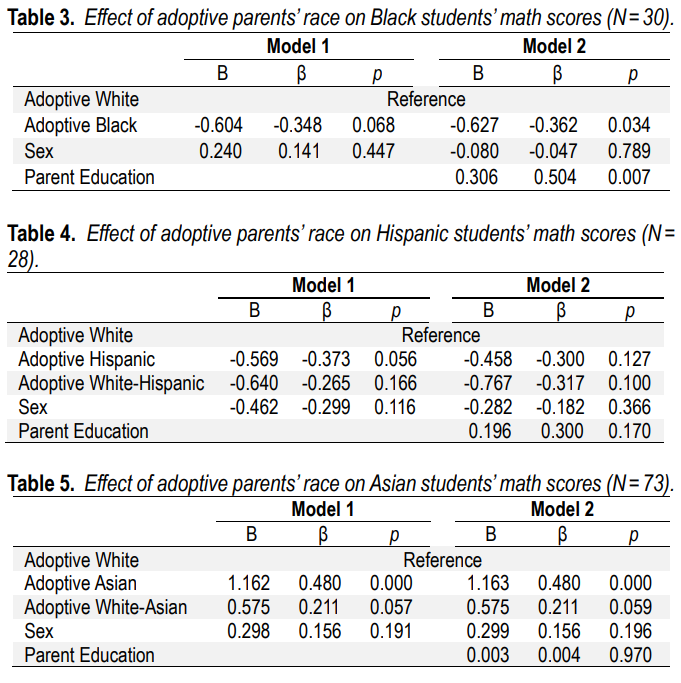

Hu, M. (2023). Does Parent Education Moderate the Effect of Adoptive Parents’ Race on Math Ability?. Mankind Quarterly, 63(4).

Separate regression for each race was used to compare the math abilities of adopted students by parents’ race. Because parents’ race affects math scores and parent education levels vary across parents’ race, education was used as a covariate.

We see in model 2, which introduced parent education, that the B coefficient of parents’ race categories is not reduced, implying no moderating effect on parents’ race. With the exception of the asian group, parent education had a moderate effect on math (B=0.306 for blacks and B=0.196 for hispanics).

Note: In Table 1, the mean education of All hispanic (biological families) should have been 2.09 (see supplemental) but it turned 2.00 in the final, published version.

References

Beaver, K. M., Schwartz, J. A., Al-Ghamdi, M. S., Kobeisy, A. N., Dunkel, C. S., & van der Linden, D. (2014). A closer look at the role of parenting-related influences on verbal intelligence over the life course: Results from an adoption-based research design. Intelligence, 46, 179-187.

Castle, J., Rutter, M., & Sonuga-Barke, E. J. (2010). Institutional Deprivation, Specific Cognitive Functions, and Scholastic Achievement: English and Romanian Adoptee (ERA) Study Findings. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 75(1), 125-142.

Doom, J. R., Gunnar, M. R., Georgieff, M. K., Kroupina, M. G., Frenn, K., Fuglestad, A. J., & Carlson, S. M. (2014). Beyond stimulus deprivation: iron deficiency and cognitive deficits in postinstitutionalized children. Child development, 85(5), 1805-1812.

Doom, J. R., Georgieff, M. K., & Gunnar, M. R. (2015). Institutional care and iron deficiency increase ADHD symptomology and lower IQ 2.5–5 years post‐adoption. Developmental science, 18(3), 484-494.

Ellis, B. J., Abrams, L. S., Masten, A. S., Sternberg, R. J., Tottenham, N., & Frankenhuis, W. E. (2022). Hidden talents in harsh environments. Development and psychopathology, 34(1), 95-113.

Finet, C., Vermeer, H. J., Juffer, F., Bijttebier, P., & Bosmans, G. (2019). Remarkable cognitive catch-up in Chinese Adoptees nine years after adoption. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 65, 101071.

Flynn, J. R., te Nijenhuis, J., & Metzen, D. (2014). The g beyond Spearman’s g: Flynn’s paradoxes resolved using four exploratory meta-analyses. Intelligence, 44, 1-10.

Fuglestad, A. J., Georgieff, M. K., Iverson, S. L., Miller, B. S., Petryk, A., Johnson, D. E., & Kroupina, M. G. (2013). Iron deficiency after arrival is associated with general cognitive and behavioral impairment in post-institutionalized children adopted from Eastern Europe. Maternal and child health journal, 17(6), 1080-1087.

Gunnar, M., & Quevedo, K. (2007). The neurobiology of stress and development. Annu. Rev. Psychol., 58, 145-173.

Hearst, M. O., Himes, J. H., Spoon Foundation, Johnson, D. E., Kroupina, M., Syzdykova, A., … & Sharmonov, T. (2014). Growth, nutritional, and developmental status of young children living in orphanages in Kazakhstan. Infant Mental Health Journal, 35(2), 94-101.

Humphreys, K. L., King, L. S., Guyon-Harris, K. L., Sheridan, M. A., McLaughlin, K. A., Radulescu, A., … & Zeanah, C. H. (2022). Foster care leads to sustained cognitive gains following severe early deprivation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119(38), e2119318119.

Jensen, A. R. (1997). Adoption data and two g-related hypotheses. Intelligence, 25(1), 1-6.

Juffer, F., & Van Ijzendoorn, M. H. (2005). Behavior problems and mental health referrals of international adoptees: A meta-analysis. jama, 293(20), 2501-2515.

Kumsta, R., Kreppner, J., Rutter, M., Beckett, C., Castle, J., Stevens, S., & Sonuga-Barke, E. (2010). III. Deprivation-specific psychological patterns. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 75(1), 48-78.

Lasker, J., & Kirkegaard, E. O. W. (2022). The Generality of Educational Effects on Cognitive Ability: A Replication.

Lindblad, F., Dalen, M., Rasmussen, F., Vinnerljung, B., & Hjern, A. (2009). School performance of international adoptees better than expected from cognitive test results. European child & adolescent psychiatry, 18(5), 301-308.

Loman, M. M., & Gunnar, M. R. (2010). Early experience and the development of stress reactivity and regulation in children. Neuroscience & biobehavioral reviews, 34(6), 867-876.

McCall, R. B. (2011). IX. Research, practice, and policy perspectives on issues of children without permanent parental care. Monographs of the society for research in child development, 76(4), 223-272.

Odenstad, A., Hjern, A., Lindblad, F., Rasmussen, F., Vinnerljung, B., & Dalen, M. (2008). Does age at adoption and geographic origin matter? A national cohort study of cognitive test performance in adult inter-country adoptees. Psychological Medicine, 38(12), 1803-1814.

Ritchie, S. J., Bates, T. C., & Deary, I. J. (2015). Is education associated with improvements in general cognitive ability, or in specific skills?. Developmental psychology, 51(5), 573-582.

Sonuga-Barke, E. J., Kennedy, M., Kumsta, R., Knights, N., Golm, D., Rutter, M., … & Kreppner, J. (2017). Child-to-adult neurodevelopmental and mental health trajectories after early life deprivation: the young adult follow-up of the longitudinal English and Romanian Adoptees study. The Lancet, 389(10078), 1539-1548.

Stevens, S. E., Sonuga-Barke, E. J., Kreppner, J. M., Beckett, C., Castle, J., Colvert, E., … & Rutter, M. (2008). Inattention/overactivity following early severe institutional deprivation: presentation and associations in early adolescence. Journal of abnormal child psychology, 36(3), 385-398.

te Nijenhuis, J., Jongeneel-Grimen, B., & Armstrong, E. L. (2015). Are adoption gains on the g factor? A meta-analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 73, 56-60.

Van den Dries, L., Juffer, F., Van Ijzendoorn, M. H., & Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J. (2009). Fostering security? A meta-analysis of attachment in adopted children. Children and youth services review, 31(3), 410-421.

Van Ijzendoorn, M. H., Juffer, F., & Poelhuis, C. W. K. (2005). Adoption and cognitive development: a meta-analytic comparison of adopted and nonadopted children’s IQ and school performance. Psychological bulletin, 131(2), 301-316.

Weinberg, R. A., Scarr, S., & Waldman, I. D. (1992). The Minnesota Transracial Adoption Study: A follow-up of IQ test performance at adolescence. Intelligence, 16(1), 117-135.

Zeanah, C. H., Gunnar, M. R., McCall, R. B., Kreppner, J. M., & Fox, N. A. (2011). VI. Sensitive periods. Monographs of the society for research in child development, 76(4), 147-162.