If one searches through old historical records, one will find economists praising the success made possible by the relative freedom of the Canadian banking system. Today one would hardly find modern economists holding such views. The most recent criticism of the free banking in Canada comes from Fung et al. (2017), which paper has been reviewed in Selgin’s well documented three-part series (I, II, III). This present article will also supply additional information.

Before looking over Selgin’s articles, one should read Schuler’s informative chapter on the Canadian free banking, since most of the critics highlighted by Fung et al. have already been addressed there. These authors first listed several reforms which, according to them, significantly improved the banking system. The main problem, Selgin argued, was that most of these reforms originated from the bankers themselves. Perhaps what made such outcome possible is the fact that Canadian bankers often were in agreement with each other, as opposed to the United States, where Western and Eastern bankers often were in disagreement (Johnson, 1910b).

The Bank Act of 1871 imposing double liability on shareholders. As Selgin noted, however, most shareholders were already subject to double liability. Moreover, one bank, the Bank of British North America, was actually exempted from the double liability provision, which seems to suggest, oddly, that existing banks were not constrained by any increased liability.

The Bank Act of 1880 provided note holders a first lien (or charge) on the bank’s asset. This innovation also is another one of the Canadian bankers’ reform proposals. Especially, one which, Johnson (1910b) said, “gives rise to such general confidence in the ultimate convertibility of a bank note that the notes of a failed bank, on account of the interest they bear, sometimes command a premium.”

The Bank Act of 1890 imposed note redemption. This is probably the most significant argument put forth by Fung et al.: the non-uniformity of Canadian banknotes. Supposedly, they were not being traded at par value. Only after the Banking Act of 1890 did Canadian banknotes achieved uniformity. According to them, “The major improvements in Canada’s media of exchange were almost entirely due to provisions of the Bank Act of 1890.”

Schuler (1992) indicated that note discount did not exceed 1% and merely reflected transaction costs. Selgin observed that branch banking allowed discounts to diminish over time and, most importantly, that only banks without a branch in the neighborhood incurred a discount on notes (which Fung should have known since they cited a passage from Breckenridge saying exactly this). Moreover, railroads were of small size, still developing, and most people lived far away from the cities, most of which were small cities. The lack of branches outside of the most prosperous communities was owing to the lack of profit of extending branches thus far due to the surroundings. In a later article, Selgin further argued :

Considering how sparsely populated many parts of Canada were, even compared to remote parts of the United States, and the small size of its railroad network (in 1880, Canada had fewer than 9,000 miles of railroad, as compared to more than ten-times that mileage in the United States), this near-elimination of Canadian banknote discounts was itself a remarkable achievement. But it was far from exhausting the private sector’s capabilities.

Another factor that would have contributed to the same outcome was the establishment of clearinghouses, first in Halifax in 1887, and then in Montreal in 1889. That others would eventually have been established without any government encouragement seems highly likely. (As it happened, clearinghouses were established in Hamilton and Toronto in 1891, in Winnipeg in 1893, and in St. John, New Brunswick, in 1896.)

Finally, it should be noted that the 1890 Act itself was an idea of the bankers and that the agreement of redeeming at par each other’s notes in their separate neighborhoods was achieved before the Act passed. The most convincing piece of evidence is the refusal by the bankers of an alternative based on the 1864 US National Bank Act, which imposes every banks to accept at par the notes of all other banks, on the grounds that notes should be accepted from circulation instead.

But, generally, the issuance of private bank notes failed in many accounts according to Fung et al. (2017). One of their point looks serious. There was considerable counterfeiting of bank notes. To quote:

Dickerman’s United States Treasury Counterfeit Detector of October 1899 lists counterfeit Canadian bank notes. The list contains counterfeit $2 of 3 banks, counterfeit $4 of 5 banks, counterfeit $5 of 10 banks, and counterfeit $10 of 9 banks. Speer (1904, chap. 30) describes the spring of 1880 in which “Canada was flooded with the most dangerous counterfeit bills ever put in circulation”(167).

It doesn’t follow that the counterfeits could fool experienced bank tellers. In fact, one of the references pointed out by Fung et al. admitted those were poorly made. Of particular importance, Selgin said that if counterfeit was actually a problem for the banks, it is curious there was no record about it. Yet, the quote “Canada was flooded with the most dangerous counterfeit bills ever put in circulation” deserves a proper response. This quote comes from the following book: Memoirs of a great detective, incidents in the life of John Wilson Murray. But which book also contained the answer to our question.

In Chapter 30, The Millions Dollar Counterfeiting (Murray, 1904, pp.152-155), the main protagonist, John Wilson Murray, who was actually a renowned detective, acknowledged that the counterfeiter, named Edwin Johnson, was the greatest master he has ever seen in his craft. From Murray’s perspective, the fault was the counterfeited bills were actually too perfect, even more beautiful than the real ones. And to better understand how exceptional this case was, even Harrington, the signer of the $5 bill of the Government issue of 1875, could not detect the forgery of his own signature. Despite this, one expert took this bill to the Treasury Department to check the series of numbers, and that is how the counterfeit was discovered. Surely, not every counterfeiter is Edwin Johnson. This only reference put forth by Fung et al. isn’t very compelling.

Even if private banknotes were to be counterfeited, government notes would perform worse. As selgin (1988) once remarked, “The likelihood of detection of counterfeit notes is inversely related to their average period of circulation. It rises with the frequency with which the notes pass under the specially trained eyes of tellers at the legitimate bank of issue.” And he also noted that commercial banknotes circulate for a short period until returning to their original source, while fiat monies, which qualify as legal tender, circulate until they wear out.

Another supposed defect considered in Fung et al. (2017) is the discount of notes owing to bank failure until solvency is resolved. They argued that the immediate par redemption was the ideal solution, which one provision of the 1890 Act supplied. Selgin replied that the notes of failed banks generally maintained their value. While the total losses of all creditors of failed banks between 1867 and the end of the century amounted to less than 1% of their obligations, Fung et al. put emphasis on other aspects of the troubles suffered by note holders. They mentioned two exceptional cases: the failure of the Consolidated Bank of Canada and of the Maritime Bank of the Dominion of Canada. The former bank had note holders who submitted to discounts of 10-25% rather than wait for payment, while the latter redeemed payments after 2 years. The case of the Consolidated Bank seems to be obscure, due to its unreported losses and lack of precise information, and we only know that a broker purchased the assets for $260,000, assumed all liabilities and made a 25% dividend payment to shareholders. On the other hand, the case of the Maritime Bank is simply explained by the fact that one of the depositors was a representative of the Imperial Government who claimed priority over the other creditors and set a suit in motion which made the situation worse. Focusing on exceptional cases like those is obviously misleading, as payments were made within few months in most cases.

The next of their argument is an odd one. Restriction on the growth of money supply is needed to avoid inflation. Other historical records of free banking simply deny this. There was for instance no inflation in Scotland and its note issuance was even more relaxed than Canada. And, as Johnson (1910a, p. 59) reminds us, competition has a self-regulating mechanism preventing it from issuing more notes than what the public wants. The real reason why the people have faith in bank notes is because the notes are always honored by the banks and never fail to stand the test of the clearing house.

The last point regards uniformity. Fung et al. cite several authors as proof there were note discounts and those were seen as a big annoyance. The only cited author who complained about note discount was Breckenridge. Yet Johnson, cited several times by Fung et al., mentioned that discounts were non-existent and people weren’t concerned at all. More importantly, Fung et al. provide no data on how large they were.

Thus, after concluding that private bank notes were unsafe, they argue that government-issued notes (Dominion notes) improved the situation in only one aspect, which is safety, while failing to improve other aspects, namely, ease of transacting, counterfeiting, scarcity, and uniformity (at least until the 1890 Act). They considered the Provincial Note Act of 1866 as quite significant. It gave protection against runs. Since there was never a run on these notes, they believe that these notes improved the quality of the medium of exchange.

This doesn’t prove Dominion notes were successful. Consider they could be issued up to $9 million, of which 25% were to be backed by gold and 75% by government securities, and any amounts beyond these limits backed 100% in gold (Kianeff, 2004). Such high reserve requirement sacrifices elasticity and causes fewer funds being devoted toward productive investment. On top of that, the outstanding notes amounted to a mere $3 million, hardly enough to cover for the cost of implementing it. The Government encouraged banks to retire their own notes and to issue instead Dominion notes. Even the prohibition of the private issuance of small denomination was meant to help government-issued notes. In the end, only the Bank of Montreal retired its own notes in exchange for the Provincial ones, and this was for the purpose of collecting the $2,250,000 that the government owed it. This was just the beginning however. Since the Provincial notes had legal tender status, the Bank of Montreal now seeks to adopt independent policies at the expense of the “solidarity” of the Canadian banking system, a feature that was one of its greatest strength (Johnson, 1910b). To quote Selgin:

Consequently it became, not merely disinclined to offer its assistance to any of its rivals in need, but inclined to resort to stratagems, such as that of refusing to accept (as it had routinely done in the past) drafts on Montreal in lieu of legal tender in settlement of interbank dues (ibid., p. 182), calculated to embarrass them. It was (again, according to Breckenridge) owing to these and other such subtle effects of the Provincial Notes Act that Canada suffered one of its only (minor) banking panics, in 1868, among other “remoter” consequences (ibid., p. 194).

To appreciate the relevance of the solidarity (or unity) of the banking system, Johnson (1910b) let us consider the following points: Over 50% of the banking business was done by only 6 banks, bank managers being trained experts, each managers of the six largest banks having in charge of more than a hundred branches being watchful of the global situation, a banker’s association through which bankers are informed of the legislation affecting their business, the mutual interdependence of the banks prevents independent policy, especially if met with the disapproval of the banking fraternity, the rule that one merchant can borrow from only one bank, a practical unanimity in opinion among bankers. This coherence leads one to believe that the Canadian system behaves as one single institution. This aspect is definitely undervalued in all discussion related to free banking I came across thus far.

Based on their wrong conclusion that the private issuance of banknotes in Canada failed in many respects, Fung et al. argued that digital currencies today will bear the same shortcomings. There are two significant arguments.

First, Fung et al. claim that private digital currencies can become valueless and disappear, which could never occur to government issued fiat currency because they have a legal tender status. But the fact that historical records of free banking supports the principle that good money drives out bad ones under genuine competition whereas Gresham’s law only applying when legal tender laws are enforced gives us no reason to believe it would be any different with digital currencies. Selgin (2008) illustrates this principle by telling us about the story of the private sector at providing Great Britain with coins that were widely accepted, due to competition making these almost impossible to counterfeit convincingly unlike regal coins, and to provide adequate solutions to their small-change shortage problems during the 18th century. Once again, Fung et al. fail to supply reasons to believe that the government is more apt than private institutions to find the best solutions to their problem. As Selgin reminds us, the digital currency industry is still maturing, and it’s too early to draw conclusions right now. And he later argues that while legal tender laws may suffice to render fiat currencies valuable in the settlement of certain preexisting debts, they have no bearing at all on such currencies’ value in spot transactions. Furthermore, legal tender currency is surely far more inflationary in nature than, for instance, the bitcoin with its quantity limit kept at 21 millions.

Secondly, Fung et al. also claimed that private digital currencies won’t be uniform. As Selgin rightly noted, the discount on banknotes “mostly reflected the costs brokers stood to incur in getting them redeemed, including the costs of receiving, sorting, and storing the notes and, once enough were accumulated, those of bundling and sending them on their way back to their places of origin via mail stage, railway mail car” whereas the redemption of digital currency is achieved by “means of a few keyboard strokes, by which light pulses are sent hurtling through glass-fiber cables, at speeds lately approaching that of unimpeded light itself”.

Finally, Selgin remarked that Fung et al. overlook the main strength of the Canadian banks, the elasticity of its currency. In this earlier article, Selgin referred to a collection of old newspapers featuring especially 3 articles that supply strong evidence that the free issuance of notes in Canada was successful.

This is a goldmine. The first article reports (citing J.F. Johnson) that Canada’s success lies on the elasticity of its currency, solidarity of its banking system, its large branch banking system, clearing houses, lack of legal tender quality and lack of bank note insurance. The second article (citing Carroll Root) shows a graph depicting the monthly change in note circulation in Canada, Scotland and the United States, lamenting that the inelasticity of the US currency is reflected by its failure to meet the high demand during crop-moving season. The article also tells us that in the U.S. “there was only 6 per cent change in circulation during the two years 1894 and 1895, and the most of this change is accounted for not by the changing needs for currency at different periods of the year, but by the sales of United States bonds, which made it convenient for banks to increase their cirulation.” and concludes that “the cost of moving the crops is much lower in Canada than in the United States, where rates of interest go up and down without materially changing the supply of currency.” The third article (written by Andrew Carnegie) thinks no better of the U.S. with its title: “The Worst Banking System in The World”. The author argues that a large amount of capital is diverted away from productive investments because bank note issuance must be based upon an equal amount of government bonds (which turned out to be unsafe) instead of the banks’ assets. He contrasts the U.S. situation to that of Canada with its notes enjoying elasticity, first lien, and double liability.

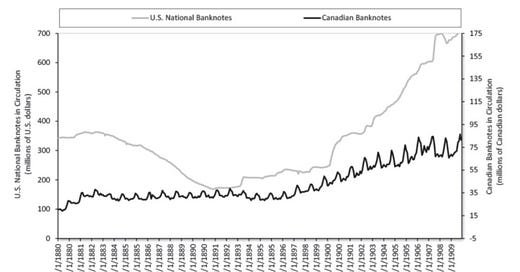

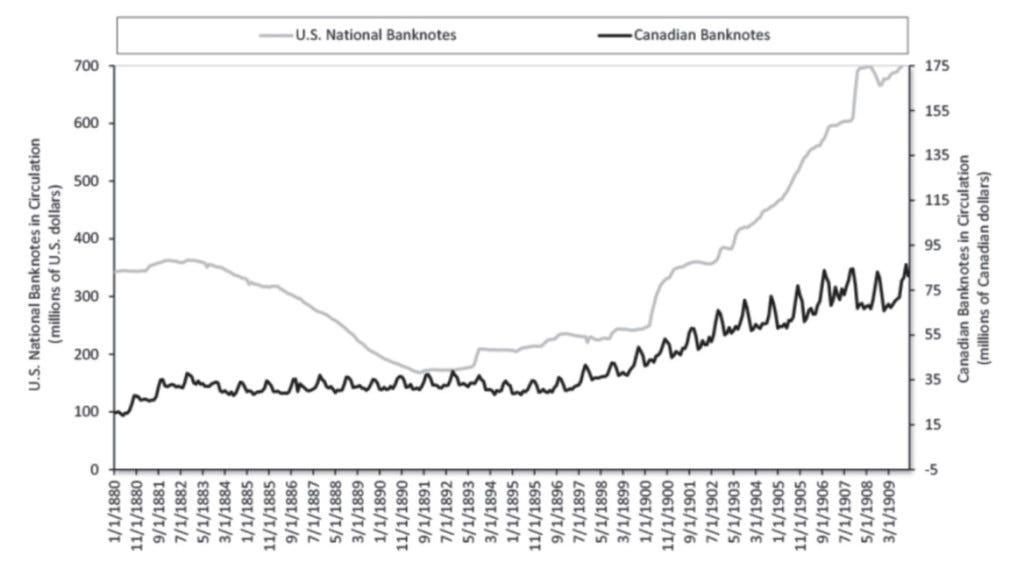

Selgin then supplies a graph showing how well and fast the canadian banknotes circulate to accomodate the demand, compared to the inelasticity of the US notes, which was the main cause of the financial crises the country suffered (Selgin, 2016).

Although there should be no discussion anymore, the great elasticity of Canada’s currency has been challenged by Kianeff (2004). Private note issuance failed to meet the high demand during the U.S. panic of 1907. Instead of acknowledging that the law restricting note issue to the paid-in capital has greatly impaired the banks only during this period, which Kianeff is fully aware of, he arrives at the conclusion that the currency is inelastic and needed supplies of government notes. As if the law wasn’t the root of the problem. How remarkable.

A less biased perspective is provided by Johnson (1910b). The panic of 1907 did not result in any run or suspicion about banks’ insolvency. This is because the bankers saw it coming. In January 1907, bankers have been urging upon their customers and shareholders the necessity for caution, as they knew the feverish activity during 1906 couldn’t go on much longer. As Johson describes: “The demand for capital had outrun the supply, and the strain upon the banking resources every bank manager knew had reached the danger point.” Of course it wasn’t sound to immediately contract the credit, so they reduced it gradually. And when the government tried to help during the downturn of 1907, the banks did not believe it was necessary. The call for an emergency issue of Dominion notes only amounted to $5 millions, which leads Johnson to conclude that “The bankers understood the situation better than did the minister of finance.” And how did those bankers handled the situation after the 1907 panic hit them? According to Johnson (1910a, pp.123-124) again, the banks accumulated reserves during 1907 by restricting loans and by 1908 they now had enough reserves to increase loans even beyond the needs of Canada.

Since the seasonal shock of the demand for notes is essential in explaining the crises that occurred in the U.S. and impacted Canada in the process, one may wonder how well this hypothesis generally holds. Fortunately, the seasonal-shock hypothesis has already been empirically tested by Champ (1996) using monthly data over the period 1880-1910. The relevance of the model, confirming the hypothesis, was the observation of a gross flow of funds between regions despite net flows being non-existent. Several findings were reported: 1) banknote circulation varies seasonally in Canada (high during the fall) but not in the U.S., 2) nominal interest rates vary seasonally (with nominal rates being highest in the fall) in the U.S. but not in Canada, 3) bank reserves and reserve-deposit ratio show seasonal volatility in the U.S. but not in Canada, 4) both nominal loans and deposits show small seasonal variation in Canada but larger in the U.S. Finally, with respect to business cycles (specifically, the panics of 1884, 1893 and 1907), reserves and reserve ratio show unusual deviation from trend in the U.S. but not in Canada, and while loans and deposits show more volatility in comparison, it was once again more serious in the U.S.

Finally, we know that this free banking episode ended in 1935. And about this, there are several studies which provide quite an interesting look at the establishment of the Central Bank. Bordo & Redish (1987) analyzed the studentized regression residuals in order to detect whether the evolution of price and exchange rate series changed after the introduction of the Bank of Canada. Because that wasn’t the case, they suspect the Bank of Canada was established for purely political reasons, rather than economic needs. Grodecka-Messi (2019) used a difference-in-differences regression to compare the effect of the passing of the Bank of Canada Act on treated banks (those affected by the cap on note issuance) and control banks (those unaffected). It appeared that the return on assets of the treated banks went down slowly over time, and more than for control banks. This implies that note issue was an important source of profit and, by the same token, that the public were unwilling to shift their funds from commercial banks to central bank.

The evidence in favor of the relatively free Canadian banking system is rather strong, among others. I therefore challenge anyone to reject the strong evidence with respect to Scotland, Sweden, Chile, Belgium, or Hong Kong. But really, the list goes on.

References.

Bordo, M. D., & Redish, A. (1987). Why did the Bank of Canada emerge in 1935?. The Journal of Economic History, 47(2), 405-417.

Champ, B., Smith, B. D., & Williamson, S. D. (1996). Currency elasticity and banking panics: Theory and evidence. Canadian Journal of Economics, 828-864.

Fung, B. S. C., Hendry, S., & Weber, W. E. (2017). Canadian bank notes and Dominion notes: Lessons for digital currencies (No. 2017-5). Bank of Canada Staff Working paper.

Grodecka-Messi, A. (2019). Private Bank Money vs Central Bank Money: A Historical Lesson for CBDC Introduction. Available at SSRN 3992359.

Johnson, J. F. (1910a). The Canadian Banking System (No. 583). US Government Printing Office.

Johnson, J. F. (1910b). The Canadian Banking System and Its Operation Under Stress. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 36(3), 60-84.

Kianieff, M. (2004). Private Banknotes in Canada from 1867 (and before) to 1950. Queen’s LJ, 30, 400.

Murray, J. W., (1904) Memoirs of a great detective, incidents in the life of John Wilson Murray. London: William Heinemann.

Schuler, K. (1992). Free banking in Canada. In Experience of Free Banking (pp. 91-104). Routledge.

Selgin, G. A. (1988). The theory of free banking: Money supply under competitive note issue (p. 80). Totowa, NJ: Rowman & Littlefield.

Selgin, G. A. (2008). Good Money: Birmingham Button Makers, the Royal Mint, and the Beginnings of Modern Coinage, 1775-1821. University of Michigan Press.

Selgin, G. A. (2016). New York’s bank: the National Monetary Commission and the founding of the Fed.