The Great Depression in Britain (1873-1896) : the Myth that Deflation Lowers Economic Growth

The problems of the Great Depression (1873-1896) have been falsely attributed to secular declines in prices. To begin, it was not clear there were any troubles during this period and even if it was the case, they were of trivial importance. And the idea that the period of 1870-90s experienced lower growth rates than the 1850-70s receives only weak support. Furthermore, the period of inflation (1897-1913) was possibly associated with lower growth, lower profit, lower real wages, higher unemployment rates, and higher interest rates. This disproves the keynesian argument that mild deflation is better than mild deflation. The period of Great Depression, either taking the period of 1873-1896 or 1880-1896 disproves the idea that unemployment increases as the price level declines. The 1855-1872 period of stable prices did not necessarily have greater growth than the 1880-1896 period of deflation. The deflation of the 1873-1896 period probably did not influence growth, wasn't a source of burden for investment, as interest rates decline along with price levels, didn't induce people to consume less, wasn't associated with worsening living condition, but instead to a better standard of living. If Britain had difficulties during the Great Depression, they could be related to the lack of skilled workers and, more significantly, to the lack of major innovations and decline in exports. The causes are generally not well understood but two conclusions at least have been confirmed. First, the most important factor explaining slower growth is a fall in labour productivity. Secondly, the so-called problems in the Great Depression have nothing to do with declining prices.

CONTENT [Jump links below]

1. An introduction to the theories about deflation

2. The Great Depression of 1873-1896 in Britain

Deflation

GDP (per capita)

Investment, profits, and debts

Unemployment

Consumption

3. The debated causes of the Great Depression in the literature

4. Lord Keynes (LK) telling lies, once againAn introduction to the theories about deflation

I also talked about it at length in my post on the so-called Great Depression the U.S. economy of 1873-1896. I'll summarize the ideas.

Selgin (1997) argued that deflation under productivity growth does not increase debt in percentage of income because increased debt burden is matched by increased income. Under deflation, consumers buy more things as prices are declining just as lenders earn more money due to greater debt payment. In the situation where borrowers expect further declines in prices, they may be able to negotiate a somewhat lower nominal interest rate. One example of this arrangement has been experienced in the U.S. economy of 1873-1896 (Higgs, 1971, pp. 97-99; Beckworth, 2007, Figure 4). Furthermore, allowing the prices to decline, instead of maintaining price stability, reduces wage-rate downward adjustments which are more likely to be a source of labor-market frictions and consequent labor misallocation than would be price declines. The enforcement of price stability can cause business cycles. Nominal prices do not adjust sluggishly to productivity changes but almost immediately. For this reason, changes in the demand for real money balances based on innovations to aggregate productivity are accommodated immediately by falling prices and well ahead of any possible monetary policy response. Thus, monetary injection may bring excess money in the hand of people and cause malinvestments, as predicted by the ABCT, which has strong theoretical relevance as well as empirical relevance.

Even the evidence does not validate the opinion that productivity-driven deflation is harmful. Friedman & Schwartz (1963 [1971], p. 93) demonstrate that the forces making for economic growth over the course of several business cycles are largely independent of the secular trend in prices. Similar conclusion is provided by Ryska (2014). Indeed, the argument that deflation causes lower growth (just because it has coincided with a relatively more difficult period) does not have strong empirical grounds. In a study using VAR analyses on the U.S. and European countries (U.K., Germany, France) of the 1880-1913, Bordo et al. (2010, pp. 536-542) found that world money supply shocks have an impact on country-specific price levels but the output was essentially driven by country-specific supply-side factors in the European countries (Figures 11, 14, 17). This implies that money was neutral, whereas money was non-neutral in the U.S. (Figure 8) only because of the presence of crises, probably due to an unstable banking system (Beckworth, 2007). Overall, it cannot be concluded from these studies that deflation (from fluctuations in country-specific monetary gold stocks) causes slower economic growth. In their own words :

Our key finding is that the European economies were essentially classical in the sense that money was neutral and output was mainly supply driven. We find that the price level shock was dominated by money supply factors, which in turn were partially explained by gold shocks. Typically these shocks did not affect output, which was largely explained by supply shocks.

For example, their Figure 11 shows the decomposition of UK output. If the solid-and-dot line "baseline+shock" is close to the solid line "actual" then the variable has an impact on ouput. But if the solid-and-dot line is close to the dashed line "baseline" then the variable doesn't have an impact on output.

Money shock is the world price level originating from world money stock changes (p. 535), supply shock is the domestic supply shocks, e.g., reflecting productivity advances (p. 536), demand shock is the (residually defined) domestic money demand shock (p. 537). We see that the only variable of importance on output (real GDP) is the supply shock (i.e., country specific supply-side factors). Figure 22 includes UK gold stock, but the behavior was just identical. Adding UK gold stock to the "baseline" or "baseline+shock" line doesn't help to match the "actual" line in any of the 3 variables. Figure 20 includes world gold production, and adding world gold to the "baseline" or "baseline+shock" causes these lines to move a little bit closer to the "actual" line in the case of money shock and demand shock, which means that world gold production is able to explain a small portion of the UK real GDP. But supply shock is still the dominant factor. All of the analysis used real GDP aggregate rather than per capita but their comment on footnote 14 says that the use of real GDP per capita does not change the results.

The above analysis can be compared with Capie et al.'s (1991, pp. 275-276, Figure 9.7a) results from vector ARMA modeling that shows that, in Great Britain between 1870 and 1913, real output (aggregate, not per capita) responded negatively to a shock in M0 and does not respond to a shock in M3 and responded negatively to a shock in prices. Price levels were positively affected by a shock to M0 but not all to M3 (see fn. 8).

The Great Depression of 1873-1896 in Britain

Deflation

Given Bordo et al.'s (2010) research, the idea that deflation has any causal relationship to output in Britain must be rejected. We have yet to enter into the details and understand what really happened.

Capie et al. (1991, p. 253) and Capie & Wood (1997, pp. 287-288) showed that money stock (on a broad definition including coin and bank deposits) grew by 1.3% a year from 1873 to 1896, and 2% a year from 1896 to 1913. Over the downswing as a whole the money stock grew by 33% and real output rose by just over 53%, while, over 1896-1913, the money stock grew by 40% and output by 36%. For 1873-1896 (or 1896-1913), they indicate that wholesale prices fell by 39% (rose by 40%) but Feinstein's GNP deflator fell by 20% (rose by 17.6%). Then, Capie & Wood (1997, pp. 287-288) argue that such price declines (1873-1896) and price increases (1896-1913) would be immaterial if the demand for money is not stable relative to income. They say that numerous studies report that the income elasticity of demand (i.e., the rate of response of quantity demand for a good due to a change in a consumer's income) is always close to unity. This means that the demand for a good or commodity (here, money) increases in the same proportion as the rise in income; this, in turn, implies that the demand for money was stable relative to income. For the UK, specifically in the 1871-1913, Turner (1991, Tables 10.4 & 10.5) found an income elasticity of demand of 0.896 in a multiple regression with M3 as dependent variable and GNP as one of the independent variables (along with bond rate and deposit rate). When M3 and non-bank financial institutions (NBFI) deposits are combined into a total quasi-money variable, the income (GNP) elasticity of money demand is 0.873. Additionally, Bordo & Schwartz (1981, Table 1, row 13) demonstrate that the real income elasticity of demand for money shows only a little change between 1880-1896 and 1897-1913, either in the US or in the UK; this means that money demand is not affected by the trend in price levels. Capie & Wood (1997) said that in Britain (and also the United States) the trend growth rate of money depended closely on the trend growth rate of the monetary base, which was gold. This view has been confirmed by Bordo et al. (2010).

What is usually misunderstood by people who argue that this period of deflation has caused many problems is that the economists (e.g., Selgin, 1997) whose proposition is to allow prices to decline in the face of productivity growth are arguing for a productivity-driven deflation. But things were somewhat different in Britain, where the lack of major innovation during that period was obvious (Richardson, 1965, p. 141; Crafts, 1995b, pp. 756-759). First, the higher level of consumption is influenced heavily by the favorable terms of trade which made import prices relatively cheaper (Musson, 1959, p. 217; Saul, 1969, pp. 19, 32, 38). And, according to Solomou & Catao (2000, p. 372), the declines (and increases) in import price during the deflationary (and inflationary) period(s) of 1879-1913 are partly due to nominal exchange rate appreciation (and depreciation). Second, it is without dispute that the decline in labour productivity has not been accompanied by a decline in labour cost (Musson, 1959, p. 218; Coppock, 1961, p. 230). There were many proposed causes of this decline. One is that labour was used less efficiently or that the gains from changes in technique and organisation fell off sharply, either of which would lead to a declining rate of profit (Coppock, 1961, p. 229). Another is that of declining quality of natural resources (Crafts & Mills, 2004, p. 170). In any case, the sticky nature of wages should not be held responsible for this. One has to understand beforehand the reason for the decline in labour productivity. Yet such decline argues against the idea that the period of declining prices (1873-1896) compared to the earlier period of stable prices (1855-1873) has been brought about by just productivity gains. If deflation is productivity-driven, labour productivity growth would have increased, instead of declining, thanks to increased productive efficiency (through education and better skills, method of production, greater quantity of capital goods, etc.). Third, as Selgin (1997, pp. 29-31) demonstrated, prices would decline along with costs, thus letting profits unchanged. And yet, the period of Great Depression has known a decline in profits (Saul, 1969, p. 42). Selgin also argued that productivity norm, a regime under which the price levels are allowed to vary to reflect changes in goods' unit costs of production (Selgin, 1995a, pp. 736-737; Selgin, 1997, pp. 26-27), would minimize changes in nominal wages, whereas price stability regime would induce greater changes in nominal wages.

And transport cost is not a good explanation for the price declines. Although Coppock (1961, p. 210) said that transport costs declined dramatically at that time, Coppock (1961, p. 211) also said that most transport costs account for 1/6 or 0.17% of the fall in import prices from 1872-3 to 1895-9. But costs overall have probably an influential role. Coppock (1961, pp. 212-213) cited Brown & Ozga's study showing some evidence that prices between 1830 and 1950 were driven by industrial demand (which is better termed "industrial needs" for making products, and should not to be confused with consumer demand) rather than by industrial supply. These authors argue that when industrial demand (or capacity) grows slower than does supply of products, the prices would fell because of downward cost-push on prices. Both costs and prices are lowered. The reverse would hold if industrial demand is slower than supply and in this case the rise in cost of raw materials pushes up the prices of final products. Both costs and prices are greater. This was also Capie et al.'s (1991, pp. 257-258) interpretation. This view of cost-push prices opposes the modern quantity theory which posits that inflation is solely a monetary effect, but it has been challenged by Bordo & Schwartz (1981).

Bordo & Schwartz (1981, Tables 2 & 3) analysed some of the proposed causes of the price changes in the United Kingdom between 1880 and 1913, notably the view that price levels were due to real factors (e.g., production costs) rather than monetary factors. The hypothesis that they are challenging is the one positing that the price of wheat, having an important role as both an input and as final output, has the dominant role in the fluctuations of the overall price level. One particular feature of the analysis is that they have combined UK and USA, on the grounds that "under the classical gold standard it would be incorrect to treat each country as if it were a closed economy since each country in such a monetary system must be viewed as an open economy with its money supply tied to the world price level through its balance of payments". They conducted a regression analysis (after first differencing the variables), with (log) price levels as the dependent variable and the (log) ratio money/output and (log) terms of trade (i.e., relative prices) between agricultural (primary) and industrial (manufactured) products as independent variables. When each of these variables are entered individually, the R² amounted to, respectively, 0.241 and 0.042. When they are inserted altogether, the R² is 0.349. The R² is not an effect size, and one should rely on the correlation, i.e., SQRT of R², which amounts to 0.205 for the terms of trade. This is a small/modest effect. On the other hand, the money/output ratio was truly important, i.e., price levels were related to money stock changes relative to real output. They then test Rostow and Lewis' hypothesis (which has theoretical problems according to Bordo & Schwartz, 1981, p. 116) that wheat prices were a key cause of the price movements in primary products. They use 5 separate regressions, using either irish potatoes, cotton, tobacco, corn or refined sugar as the dependent variable, and (log) money/output and (log) prices of wheat flour (or wheat for grain). Only when the dependent variable is cotton or sugar that the elasticity for wheat flour or wheat for grain is of somewhat importance (as seen by the unstandardized coefficient β'2). So, the Rostow-Lewis hypothesis of cost-push prices was rejected. Even so, that does not concern the point made by Brown & Ozga regarding reduced production costs.

If one wants to explain why Britain lagged behind the U.S. and Germany, deflation can hardly be a relevant factor. Bordo et al. (2010) reported that prices fell by 22%, 10% and 6% in the U.S., U.K., and Germany, respectively. Not only the U.S. growth was stronger, but it has also experienced a series of banking crises, unlike the U.K., which would have certainly hurt economic growth (Capie & Mills, 1991).

Even though the said period is not one of prosperity (due to repeated boom-bust cycles), it was still a good period. Even so, people didn't feel good at the idea of deflation, and this may be due to the fact that their nominal wages were being reduced (Musson, 1959, p. 201).

GDP (per capita)

The data on GDP growth is taken from Maddison's (2003 pp. 59, 61) figures, based on Feinstein (1972) for the years 1855-1960. At first glance, it would seem that the period before 1873 is associated with a stronger growth. Using Stata and the above numbers, I plot the following graph :

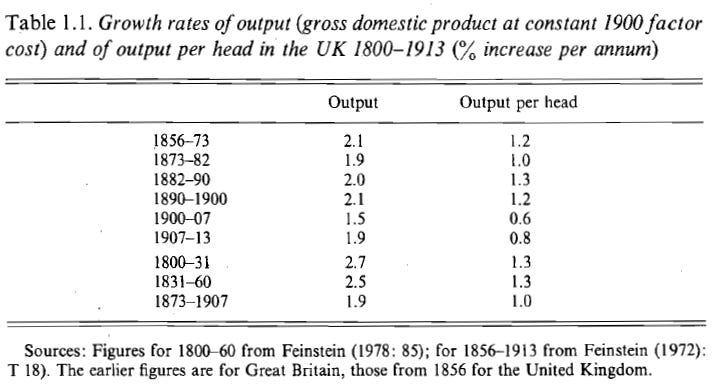

twoway (scatter UK_GDP_per_capita Year), ytitle(UK GDP per capita) xtitle(Year) title(U.K. GDP/capita Maddison 2003 based on Feinstein 1972)The spreadsheet is available here. I averaged the numbers for the following periods : 1855-1872, 1873-1896, 1880-1896, 1897-1913. The respective growth rate averages are 1.38%, 1.06%, 1.43%, 0.89%. Clearly, the period of inflation after 1896 has been the worse. The period of 1855-1872 does not necessarily appear to have been better than the period of 1980-1896. A look at the figures given by Floud (1981, p. 7) allows us to reach the same conclusion :

Similarly, the numbers on real growth rates of industrial production per head show that the inflationary period didn't do better but probably worse than the deflationary period (Saul, 1969, p. 37).

Something seems to be happening at the end of the 19th century and, indeed, Musson (1963) and Coppock (1964, p. 390) revealed that there is no economic growth, after excluding building, in the inflationary period of 1896-1913. We can confirm this impression from Feinstein's (1990) Table 2, which is also based on Feinstein (1972) :

Concerning Figure 1, Feinstein (1990, p. 351) concluded that the GDP estimates based on income data is more reliable because many indicators of industrial output are estimates of raw material inputs and many indicators for output of services are based simply on linear interpolation between decennial census figures for the numbers employed in those services, in some cases with the addition of an assumed steady increase in productivity. The latter, in particular, underestimates cyclical variations. It is clear from the income data based estimates that the growth becomes stronger, and the deceleration more serious at the end of the 19th century. Concerning Tables 2-3 shown above, all GDP series agreed on something : the fact that the period of 1899-1913 has been the worse by far. The estimates of GDP per worker between 1856-73 and 1882-99 seem very close when based on income data and expenditure data. In all three series, we don't see a dangerous change in pace occuring in the Great Depression. The significant change really happened after the period of Great Depression. Feinstein (1990, p. 340) splits the periods not at 1896-7 but at 1899 because it is after that year that the growth of real wages were decelerating, which event is associated with slower growth and the turnaround in the terms of trade which began to be unfavorable to Britain (Saul, 1969, p. 29).

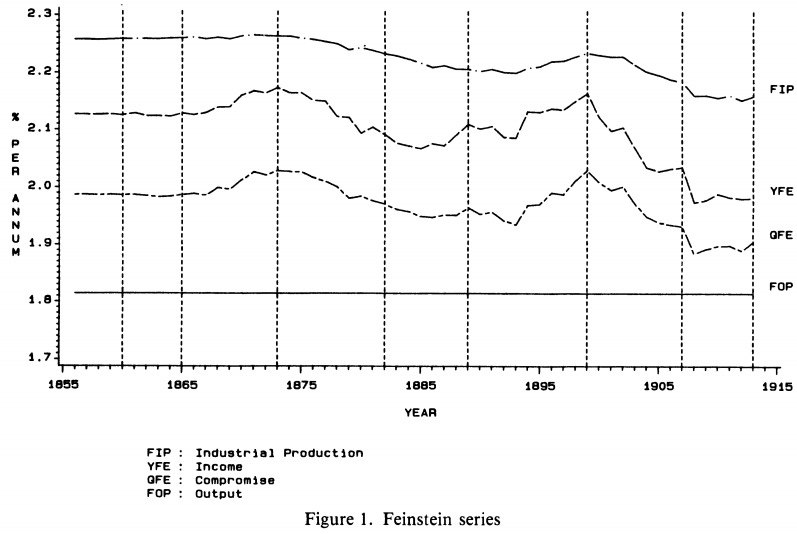

There is more to say. Crafts et al. (1989a, Figure 1) criticized earlier studies for not using inappropriate models. They say that the linear regression model commonly used takes the form Yt = α + βt + ut, with α the intercept, β the slope, u the error term which is assumed to be a stationary error process (i.e., its mean, variance and autocovariances are finite and constant through time). This model, which accounts for nonstationary behaviour in Y by the deterministic trend α + βt which leaves the cyclical component ut as a stationary series of deviations around this trend function, corresponds to what Nelson & Plosser (1982) call TSP or trend-stationary processes. Another model takes the form Yt = Yt-1 + β + ɛt, where Yt-1 is the lagged value of the dependent variable, ɛt is a stationary but not necessarily serially uncorrelated with mean zero and constant variance, β being the fixed mean of the differences, the growth rate in the present context. A model which corresponds to DSP or difference-stationary processes. The distinction is important because "If GDP is of the TSP class, then all variation in the series is attributable to changes in the cyclical component, whereas if GDP is a DSP its trend component must be a nonstationary stochastic process rather than a deterministic trend, so that an innovation of GDP has an enduring effect on the future path of the series. Thus treating GDP as a TSP rather than as a DSP is likely to lead to an overstatement of the magnitude and duration of the cyclical component and to an understatement of the importance and persistence of the trend component." (pp. 109-110). Crafts et al.'s trend-plus-cycle model takes the form Yt = αt + βtt + ut, where αt = αt-1 + at, βt = βt-1 + bt, ut = p1ut-1 + p2ut-2 + et (given that the error process u, seems to be adequately modelled by an AR(2) process, which allows a cyclical component to be incorporated; for the definition, a process considered AR(1) is the first order process, meaning that the current value is based on the immediately preceding value and AR(2) process has the current value based on the previous two values; see Investopedia), with at, bt, et being zero mean, serially uncorrelated, and individually independent processes. This model thus allows the slope and intercept (growth rate) to drift continuously from period to period by way of random walks. According to them, "Such a formulation avoids forcing the slope and intercept coefficients to change at discrete points in time; rather they are allowed to vary sequentially in a manner that has been found to provide a sensible explanation for the evolution of many economic time-series." (p. 111). The reason for using this approach is because, they say, "it is generally agreed that the actual rate of growth was subject to fluctuations stemming from short-term shocks to aggregate demand" and that "It is therefore important that changes in the unobservable, but estimatable, trend rate of growth are the result of appropriate time-series decomposition procedures rather than the outcome of an arbitrary division of the time-series into cyclical and trend components" (Crafts, 1989a, p. 105). Figure 1 below shows the time paths of β over time. The GDP (aggregate, not per capita) growth rate throughout the entire period of 1855-1915 does not change at all. That is, there is slowdown of growth rates after 1873 or 1899. The strongest change occurred after 1899, with growth rate per year down by only 0.1%.

Crafts et al. (1989b) say, once more, that "it is common practice to regard the trend as a deterministic function of time and the cyclical component as a stationary process that exhibits stochastic movement around the trend" (p. 47). Indeed, trend-cycle analysis in the literature on British economic history of the industrialization era has been generally to detrend series using a 9-year moving average and to investigate cycles by looking at deviations from this moving average. An approach that should be avoided. Crafts et al. (1989b) replicated the above trend-plus-cycle model (which decomposes trend and cycle components) by using Hoffman's industrial production, which covers the whole of the period 1700-1913. That data have been criticized for applying inappropriate weighting on some sectors of activity for certain years. The authors thus applied the corrections of Harley (1982) and Lewis (1978) to Hoffman's data. Figure 4 below shows the trend growth component, that uses their preferred estimates (Q3) which adopts both Lewis and Harley's correction. It is clearly visible that the decline in growth has started during the 1850s-1860s or so. In fact, the decline in growth rates is slower during the 1870-90s than during the 1850-60s, and there is no change between 1880 and 1896. Whatever events that lowered the trend growth seem to be unrelated to deflation or the Great Depression.

Greasley (1992) argued that a proper test of the climacteric hypothesis must involve cointegration test between GDP and factor input growth series. Two measures of GDP are used : an income-side (y) series from Greasley (1989) and a compromise (i.e., aggregation) series based on Feinstein's (1972) output and expenditure and Greasley's (1989) income data. He concluded that "The findings suggest that British GDP series are integrated of order one, and hence that the rate of GDP growth reverted to a constant mean rate in the period 1856-1913, which militates against the climacteric. The cointegration results also show long-term convergence of GDP and factor input growth, which counters the view that the years to 1914 represent the productivity downswing phase within the longer 'U'-shaped pattern of British productivity performance." (p. 207). This implies that GDP growth stays constant over time and that one can predict GDP growth by knowing factor input growth and vice versa because the two variables move together.

Whether we side with Feinstein or with Crafts and Greasley, it can only be concluded that deflation has not been associated with slower growth.

Investment, profits, and debts

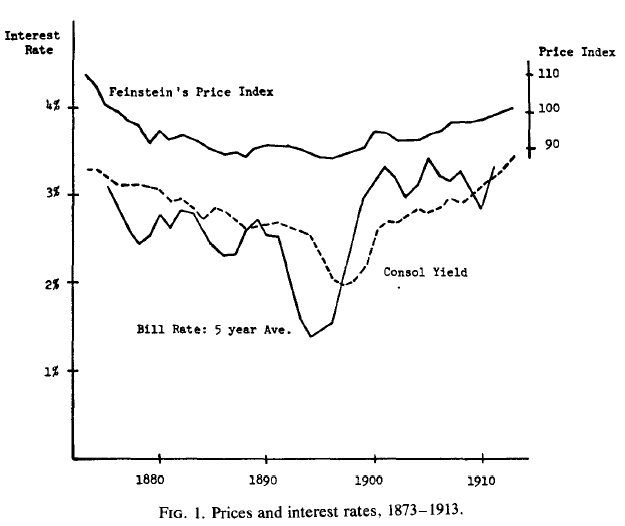

Deflation, as commonly believed, causes an increase in debt burden which, in turn, causes both lower investment and lower employment. As explained before, if deflation is productivity-driven, there is no such debt burden. Besides, Musson (1959, pp. 203-204), Saul (1969, pp. 16-18), Capie et al. (1991, pp. 271, 278-279), and Capie & Wood (1997) affirmed that interest rates fell at the same time the price levels fell. Figure 1 from Harley (1977) depicts the trend in prices and interest rates :

These authors argue that this can be easily understood by the fact that the expectation of deflation (when there are such expectations) will reduce long-term nominal interest rates. An analysis from ARMA modeling confirmed that prices do not respond to shocks in interest rates (Capie et al., 1991, Figures 9.6c & 9.7c). But interest rates responded positively to shocks in prices (Capie et al., 1991, Figures 9.6d & 9.7d). This strongly suggests that variations in interest rates are caused by expectations in prices, not otherwise. This is surely what happened in the deflationary U.S. economy of 1873-1896. And in the deflationary british economy of 1873-1896 as well. There is no debt burden, since Harley (1977, pp. 79-82) has concluded that the nominal interest rates moved accordingly to prices so that the real rates of interest remained stable between 1873 and 1912, although it should be noted that external factors (e.g., gold discoveries in the mid-1880s) have influenced the changes in interest rates. On average, the real interest rate was about 0.25% higher during the deflationary period than in the inflationary period.

The positive correlation between interest rate, known as Gibson Paradox is not a historical accident. Dowd & Harrison (2000) analyzed the U.K. in the 1821-1913 period. By using 4 price series, they tested the cointegration of price and interest rate series. The long-run equilibrium relationship holds for 3 price series. They conclude that the Gibson Paradox is not an artifact resulting from the financial effects of war. Chadha & Perlman (2014) confirmed this long-term relationship in the U.K. for an even longer period (1702-1913).

One other argument used by keynesians is that of idle resources, criticized by Hutt (1963 [2011], pp. 24-29, 54, 100), resulting from lack of investment due to depressing environment caused by lack of consumption and gloomy expectations of profits. Ashworth (1966, p. 19) argues that there was a mis-use or under-utilization of capital. Production was becoming more capital intensive. The length of the working day and limited use of shift working, which may be the result of the increased unemployment rate since the end of the boom in 1873, seem to explain the under-utilization of the productive equipment. Another source of idle resource is building. Ashworth (1966, p. 21) also informs us that too many buildings have been produced and don't contribute to economic growth. Most of the time, these buildings were used only during the appropriate season of a year. Ashworth writes :

An analogous (though lesser) influence appears in the disproportionate growth of residential towns and holiday resorts. This went on all through the nineteenth century, but it was not until fairly late that these towns were collectively big enough to have more than a negligible effect on the nation's economy. But the increase in their size and in the number of holidaymakers involved them in capital investment and labour recruitment to deal with a short seasonal peak, with the consequence that resources were seriously under-utilized for the greater part of their existence.

Ashworth (1966, p. 19) remarked that the dormitory suburbs were prominent in the seventies, but their growth in the eighties and nineties was absolutely much greater. This shows, anyway, that the under-utilization of buildings has nothing to do with falling profits or deflation or gloomy expectations. It is due to an increasing amount of bad investments.

On a related note, Ashworth (1965, p. 72) mentions that the ratio capital/output (which assumes homogeneity of capital, which makes no sense from the Cambridge economists' and austrian economists' point of view) showed a decline during the Great Depression. But he says that "Fuller utilization of existing capital, common in the later stages of a long period of heavy developmental investment such as occurred in Britain in the mid-nineteenth century, could bring down the average ratio. Changes in the type and purpose of new investment, inevitable in an industrial society, could bring lower incremental ratios." (p. 72).

Saul (1969, p. 42) takes for granted that if profits were to fall, due, e.g., to the increase in the share of wages in the sum of wages plus profits (Saul, 1969, p. 33), the industries will be less inclined to launch productive investment; finance being a major source of industrial profits. The first difficulty is theoretical. Hayek (1939) demonstrates that higher profits tend to favor investment that is less time-consuming (less capital-intensive); the consequence is a decline in profits among capital goods industries which causes a shortening of the structure of production. Weber (2009) showed that the U.S. economy has grown along with a lengthening of the production structure. The second difficulty is empirical. The period after 1896, when deflation was replaced by inflation, shows no increase in profits compared to the 1873-1896 period. Saul gives the following numbers, taken from Feinstein :

Profits/Industrial income Profits/National income

% %

1860-64 45.0 24.2

1865-69 46.0 26.4

1870-74 47.7 29.4

1875-79 43.3 26.1

1880-84 42.6 25.7

1885-89 42.2 25.2

1890-94 37.8 22.7

1895-99 40.6 24.9

1900-04 39.0 23.7

1905-09 39.5 23.5

1910-14 39.2 23.2If anything, the profits in this later period (Edwardian era) of inflation were lower, not larger. The percentage corresponding to the period of 1870-74 is the highest due to the large railway boom, biasing upward the average share of profit in national income for the Middle Victorian Era. Now, the last period, not considered yet is before 1873, e.g., 1850s-1870s, the Middle Victorian Era. When looking at this entire period, one could perceive there was inflation. But Saul (1969, p. 13) correctly argues this is wrong. There is a sharp increase in prices at the beginning of the period (1952-3) but nothing more after this. The 1855-1872 period is better characterized as one of price stability, as was noted by Coppock (1961, p. 224).

Until now, we have assumed that profits caused investment in the british case. Pesmazoglu (1951) re-analyzed Tinbergen's multiple regression analysis concluding that investment is highly influenced by profits. Unlike Tinbergen, Pesmazoglu (1951, pp. 53-56, 59-61) applied first-differences to the variables. He has established that current and past profits did not influence british home investment between 1870 and 1913, and found that variations in prices of investment goods and in the long-term rate of interest did not have an important influence on fluctuations of british home investment. He suspects that variations in income and activity in the primary producing areas which were borrowers from the U.K. probably considerably affected business expectations at home and thus, home investment.

One dissenting view is from Kennedy (1974, pp. 425-426, 429), according to whom the british wealth-holders had an aversion for risk, and favored lower-risk investments (and thus having lower yields), which promote slower growth. That risk-aversion has reduced the capital formation (by raising its cost) compared to the U.S. and Germany (Kennedy, 1974, p. 434). It has been proposed that the reason has to do with imperfect information pertaining capital market, which makes foreign investment unattractive due to higher risk (Kennedy, 1982, p. 112). British firms were more familiar with British engineering equipment than were foreigners. As a result, the existing foreign investment was skewed towards customers with a lower propensity to use British capital equipment (Kennedy, 1974, pp. 437-438). Even if we grant this point, it could also be that the cause of low-risk taking is related to the small size of many british firms and traditions of self-finance (Saul, 1969, p. 41). However, as argued above, the lower capital formation was not inherent to the Great Depression but prevailed even before and after (Saul, 1969, p. 41) :

These numbers were taken from Kuznets (1961, Table 3). In terms of net national capital formation to net national product, the ratios for the three periods were, respectively, 10.6, 10.6, 11.8. This again provides no good evidence for the idea that deflation was associated with lower investment, compared to the earlier period. Coppock (1961, p. 228, fn. 2) shows that the ratio of total investment (the sum of home and foreign investments) to national income has declined modestly by 1% between 1856-74 and 1875-96. Still another source (Lenfant, 1951, Table III, pp. 160, 166-167; see also Musson, 1959, p. 211) reports rather stable investment rates. Between 1873 and 1896, the ratio of net total investment to net income oscillated between 8% and 11 % while the ratio of net gross investment to gross income oscillated between 15% and 17%. For the inflationary period between 1897 and 1914, the numbers were 10%-12% and 16%-19%. Perhaps modestly higher.

Another version of Kennedy's argument is that the british banks were reluctant to make business on long term loans. Kennedy (1987, p. 122) cited Jefferys :

But the shock of these failures in 1878 and the resulting turn toward timidity and amalgamation in banking, and the adoption of limited liability by industry, which lessened the demand for long term loans, brought to an end in the 'eighties, this formative period of British banking. . . (1938:18)

The banks were by the 'eighties no longer showing such a readiness to act as partners in industrial concerns. They were moving further and further away from the concept of long term loans and were concentrating on an efficient national short term credit system. (1939: 119)

So, according to Jefferys, there were two reasons. First is the series of banking failures which reached a peak in 1878, and second is the absence of unlimited liability on the part of the industries. Regarding 1878, it could well be that the crash of the boom of 1870-1873 (and with it, the rising unemployment after 1873) has been the cause of these banking failures. If so, deflation would not be held responsible for the boom. Regarding liability, as argued by Saul (1969, p. 41), the small size of many firms could have been a serious hindrance. Aldcroft (1964, pp. 126, 131-132) and Ashworth (1966, p. 23) indeed remarked that british firms failed to generate economies of scales, which made it difficult to establish selling organizations and agencies for dealing with foreign markets. Two forces may be working to reinforce each other : the lack of finance prevented large-scale expansion and the small size of the firms did not attract long-term banking loans. But this has nothing to do with the supposed lack of investment. Again, the entire argument is dislocated by the fact that capital formation stayed rather stable between 1855 and 1914 (for an explanation of capital formation, see Machlup, 1940 [2007], pp. 26-27). McCloskey & Sandberg (1971, p. 105) also come to the conclusion that there is no known evidence of under-investment in research, in the new industries, in marketing or in what they call the formation of cartels.

Overall, investments, whether home or abroad, show a cyclical pattern of ups and downs. One plausible reason is the change in interest rates. Ford (1969, p. 110; 1981, p. 42) argues that the direct cost effects of the Bank Rate on domestic investment spending is probably weak; variations in Bank Rate brought changes in short-term interest rates to which investment spending was insensitive, but did not influence substantially longer-term rates to which such spending might be more sensitive. Furthermore, the nature of finance of home investment from undistributed profits (but see Pesmazoglu, 1951) and private loans rather than the Stock Exchange would lessen sensitivity to interest-rate changes and their associated cost effects. Even though Ford (1981, pp. 38-39) found a link between exports and loans, as british exports follow one or two years behind the fluctuations of british loans abroad, he suspects the relationship may also be driven by a third factor. For instance, a rising economic activity could have caused both exports and loans. Yet, it seems that overseas issues precede exports and income while Bank Rate precede overseas issues (Ford, 1981, p. 47).

In definitive, there is no evidence that a continuous decline in prices would have brought about a continuous decline in profit and investment.

Unemployment

It could be argued that when prices fall, nominal wages don't follow because of wage stickiness (workers are reluctant to wage cuts). As argued before, in the case of productivity-driven deflation, there is no increase in costs associated with sticky wage. It is not real wages that matter but the gap between real wages and productivity. Instead of blaming sticky wages, one could have blamed the declined labour productivity. But if one really wants to put the blame on deflation for the apparent wage stickiness in Britain that has supposedly caused the rise in unemployment, one needs to explain why the nominal wage in the U.S. between 1873 and 1879 has fallen by 16.11% (Newman, 2014, p. 495). One plausible reason for the difference could be due to the strong labour union in Britain (Saul, 1969, pp. 32-33).

Another related complaint is that deflation tends to increase debt and, ultimately, unemployment. That may be true of a recession, which is brought about by excessive debt (or, equivalently, insufficient savings). But not in the case of productivity-induced deflation. The data does not even support such idea.

The Table 6 from Boyer & Hatton (2002) shows that unemployment has increased between 1873 (2.8%) and 1879 (9.1%) but no more since then and yet wholesale prices continued to decline in a consistent way. This refutes the idea that continuous declines in prices causes continuous rises in unemployment. Looking at each subsequent years after 1879 until early 1890s, a decline in unemployment was the rule, not the exception. Boyer & Hatton even said that the unemployment rate among unskilled laborers was below 10% in every year from 1870 to 1892 and above 10% in all but four years from 1893-1913. Worse is the fact that the average unemployment rate in the period of 1892-1913 was greater, with 6.2%, than during the period of 1870-1891, with 5.4% (see Table 7 below). Even 5% is not particularly high (but not low either).

All other periods considered by Boyer & Hatton (2002) show that the british Great Depression has the lowest unemployment rate. These unemployment series are comparable to postwar unemployment series, thanks for adjustment to differing sources of data used for making unemployment estimates (Boyer & Hatton, 2002, p. 664). It is not reasonable to consider the 1946-1973 period, as this very low unemployment rate (coupled with a high economic growth; Crafts, 1995a, Table 1) could be attributed to an economy recovering from War, the so-called Golden Age, as demonstrated by Vonyó (2008, p. 239). Crafts (1995a) quoted Abramovitz :

Indeed, Abramovitz has suggested 'The post-World War II decades ... proved to be the period when - exceptionally - the three elements required for rapid growth by catching-up came together. The elements were large technological gaps, enlarged social competence . . . and conditions favouring rapid realization of potential'.

Besides, Saul (1969, p. 31) shows that real wages went through a strong, steady increase over time. Unemployment rates don't seem to follow neither of these trends. Feinstein (1990) has concluded, in his revised estimates of the trend of real wages, that the slowdown in real incomes at the beginning of the 20th century could be attributed to slower economic growth, although Crafts & Mills (1994, p. 192) argue it should also be attributed to a rise in the cost of living relative to the GDP deflator (a measure of price inflation/deflation with respect to a specific base year) that occurred during the Edwardian period.

This period, we must remember, was marked by inflation. If we take that data at its face value, we are tempted to conclude that deflation is more conducive of economic growth and employment. Feinstein's conclusion is consistent with McCloskey's (1970a, 1974, 1979) in that the Victorian Britain did not fail. The failure was Edwardian.

Although, one could argue from the above numbers that the period of 1855-1872 could have been accompanied with lower unemployment, the data reported by Musson (1959, p. 201) and Ford (1981, pp. 28-30, Figures 2.1-2.2) tells no such thing. For the periods of 1855-1873, 1874-1900 and 1901-1913, Musson reported unemployment rates of 4.8%, 4.9%, 4.5%, respectively. Assuming we can really trust these numbers, it seems that prices (stability, deflation, inflation) don't affect unemployment so much. But Coppock (1964, p. 394) shows, among other things, that the period of 1851-1866 is dominated by engineering, metal and shipbuilding unions which show higher unemployment rates than the other trades, although he gives no logical reason for removing them. He also said that the periods 1851-1887 and 1893-1914 were not comparable, although he provides not much information. Having made these corrections, he reports the unemployment rates for 1851-1873, 1874-1895, 1896-1914, being 5.0%, 7.2% and 5.4%, respectively. If we compare still different periods, e.g., 1867-1874, 1875-1883, 1884-1889, 1890-1899, 1900-1907, the unemployment rates are 3.9%, 4.8%, 7.0%, 4.1%, 3.9%, respectively. What is extraordinary is that the growth rates for the periods 1875-1883 and 1884-1889 were, respectively, 0.829% and 1.696% (see spreadsheet). Given Coppock's numbers, one would not have expected greater growth for 1884-1889. Besides, Coppock's numbers and those reported by Boyer & Hatton (2002) simply don't correspond. In any case, even accepting Coppock's numbers, he said that the causes of the high unemployment for 1884-1889 were due to decelerating growth of exports and decline in house-building. Wilson (1965, p. 186) explains that Coppock quotes derive in large measure from exceptionally high unemployment in heavy industries in one or two particular years - 1879, 1885 and 1886 especially, and that it is equally noticeable that the unions with a sizeable or complete stake in consumption industries - wood workers and (especially) printers and binders - contributed little to the swollen unemployment averages of the years of the Great Depression. This, then, refutes the idea that the higher unemployment was due to underconsumption. Wilson (1965, p. 186) also points to the unrepresentativeness of Musson and Coppock's figures, on the ground that labour force was 9.3 millions in 1871 and 13.8 millions thirty years later, while the total membership of the trade unions was only 1.9 millions. But under- and over-representativeness of industries in the index of unemployment are still another issue, and Boyer & Hatton (2002, pp. 647, 649) have attempted to correct for such biases, by appropriately applying weights and adjustment for, e.g., changes in composition of the unemployment index. If more recent estimates are usually corrections to earlier estimates, it is logical to believe that the most recent estimates are more reliable; for instance, Boyer & Hatton (2002, fn. 45) argued that the estimates from the Board of Trade (Feinstein) is inaccurate : "The method of weighting adopted by the Board of Trade causes textiles to be underrepresented in their index in 1894 and overrepresented in 1913." (p. 657). Furthermore, their estimate are much more consistent with the pattern of growth rates than are Coppock's numbers. There is probably more certainty that the inflationary period after the Great Depression acknowledged a greater unemployment rate.

Interestingly, Saul (1969, pp. 11, 31-32) argued that a revival in house-building during the mid-1890s (1897-1900) may have helped to reduce unemployment. We see from Boyer & Hatton's Table 6 that unemployment has declined between 1895 (7.3%) and 1900 (4.3%). Now, suppose, as we have seen, that the early 1870s were still undergoing an economic boom, precisely, a railway boom (Musson, 1959, p. 215), but that the boom has ended in 1873, as Saul (1969, pp. 13, 21, 25, 54) argued, then, we may have our explanation for the sharp increase in unemployment from 1873 to 1879. As austrian economists understood, if monetary over-expansion causes an artificial increase in investment, i.e., not backed by corresponding savings, and that this boom draws some unused resources (e.g., unemployed workers) into the market, an end to this boom would mean that unemployment tends to reach its previous, usual levels. The ABCT also predicts greater nominal wages during the boom, and this has been confirmed in the data showing a dramatic rise in nominal wages just in the years 1870-1873 (although data on wages in the railway-related sectors seems to be unknown), which is followed by a non-trivial decline in nominal wages between 1874 and 1879. The period of boom (1870-1873) has seen an increase in wholesale prices, which accompanied wages, although the ABCT does not make any assumption about absolute prices (but only relative prices).

The railway boom of 1870-1873 had severe repercussion on the U.S. economy (Newman, 2014, pp. 490-491) and probably had severe repercussion on the U.K. as well, especially if Saul's words that "the boom to 1873 was unusually pronounced in several different ways" can be trusted. There are at least two reasons for this. First, it has been argued (Saul, 1969, pp. 32-33) that the workers had the ability to force their wages up above prices in the boom years but that they were able to maintain their wages even when the unemployment was high. For this reason, nominal wages fell only slowly. The austrian economists could then argue that without what is suspected to be a credit-induced boom, the harmful and sluggish downward adjustment in wages would have been avoided. Secondly, Saul (1969, p. 25) remarked that profit margins fell among british coal owners who were facing lower prices after their investment spree during the boom years of the early 1870s. Yet, probably something more would explain the long, sustained rise of unemployment from 1873 until 1879.

Another important factor explaining the trend in unemployment could be monetary policy. The Bank of England, in response to gold loss, has restricted the credit supply, which has caused a depression in investment and employment (Brown, 1965, p. 54). Indeed, Brown (1965, pp. 57-59) put his emphasis on a sufficient reserve ratio of the Bank of England to prevent or end a boom, by raising the interest rate so as to attract gold and preventing it from flowing out. Interest rates were higher during the boom and lower during the slump but it would be more accurate to say that the central bank has raised the interest rates at the end (not the beginning) of the boom, which puts an end to the boom (Ford, 1969, pp. 108, 111-112).

Brown (1965, p. 52) says that even when foreign lending vary over a wide range, there were only minor gold movements. A theory is needed to explain the simultaneity actually observed between boom and slump in different overseas investment areas. One is that central bank policies between countries were synchronized (Ford, 1969, pp. 109-110). For instance, central banks in France and Britain move their discount rates in the same direction at the same time, although not to the same extent. Brown (1965, p. 54) noted :

At such times, the overseas booms which drew our capital abroad did not draw enough of our goods abroad to effect the transfer of our intended loans. Incipient gold-loss therefore forced the Bank of England to apply restrictive policies which stopped the loss, but only at the cost of depressed total investment and consequent unemployment.

Brown (1965, p. 51) cites a study showing that the interest rate correlates with capital exports (net foreign investments). This means that money became scarce in the country because it was lent abroad. However, during the lending booms of 1872 and 1890, foreign lending (and the external drain of gold it would result) has been largely offset by an additional rise in demand for british exports (Brown, 1965, p. 58). This should have prevented the external drain of gold, the rise of interest rate by the Bank of England, and thus the rise in unemployment.

In general, the argument that interest rates covary with unemployment rates is somewhat attenuated because, if interest rates (through its effect on money supply) affect unemployment, one would also suspect that money supply would affect economic growth. Capie & Mills (1991) conducted a vector autoregression (VAR) analysis showing that there is a strong cyclical money-output in the U.S., but only a weak relationship in the U.K., and they argue that the difference may be due to the fact that the U.S. has experienced several banking crises, probably caused by a weak banking system having no branch banking (Beckworth, 2007). There were, however, no banking crises between 1870 and 1913 in the U.K.

Consumption

Generally, falling profits and rising wages are considered as symptoms of a recession. But also declining consumption. This one does not apply here either. Falling prices did not induce people to consume less (Musson, 1959, pp. 199-200; Saul, 1969, p. 14). Musson describes in this way :

Prices certainly fell, but almost every other index of economic activity — output of coal and pig iron, tonnage of ships built, consumption of raw wool and cotton, import and export figures, shipping entries and clearances, railway freight and passenger traffic, bank deposits and clearances, joint-stock company formations, trading profits, consumption per head of wheat, meat, tea, beer, and tobacco — all these showed an upward trend. These facts were visible to observant contemporaries such as Giffen and Marshall, who, despite the loud complaints of falling prices and profits, of overproduction and unemployment, pointed out that the country was in no real sense depressed. ... On the other hand, there was an overwhelming mass of opinion ... that conditions were bad. The complaints were not, of course, continuous: the depression, we know, was not unbroken, the clouds periodically lifted, and the atmosphere brightened. There were, in fact, cyclical fluctuations, with booms reaching peaks in 1882 and 1890, and slumps descending to troughs in 1879, 1886, and 1893. But the booms were short-lived, the slumps prolonged, and business never really escaped from the atmosphere of uncertainty and depression.

... There is no doubt that, on the whole, the condition of the working classes improved during this period. Real wages rose considerably, there was a redistribution of the national income in favor of wage earners, pauperism declined, deposits in savings banks grew steadily, and consumption per head of foodstuffs, beer, tobacco, and similar products rose.

And Wilson (1965, p. 185) reported that the increase of imports, which has certainly contributed to the decline in prices, pointed to a growth of miscellaneous wants amongst the consumers. To support this view, Wilson says that the number of persons engaged in transport, commerce, art and amusement, literary, scientific and educational functions had risen between 1871 and 1881 from 947,000 to 1,387,000, or from 8.8% to 11.7% of the self-supporting population. It's hard to believe that a depressing economy would experience a rise in such miscellaneous activities. This is more a symptom of prosperity than of depression.

Supple (1981, p. 129) report data from Feinstein (1972) on consumers' expenditures as a proportion of UK GNP. For the periods 1870-79, 1880-89, 1890-99, 1900-09, 1904-13, the percentages were 87.8, 87.8, 87.9, 85.5, 84.5. In other words, the propensity to consume is stable during the deflationary period but declined (along with growth) after 1900, i.e., during the inflationary period. Consumption, in fact, is not the leading factor causing economic growth, as there are empirical evidence showing that consumption crowds out investment and, thus, higher consumer spending leads to lower economic growth (Emmons, 2012). This, too, is consistent with Weber's (2009) study showing that the early capitalism (1900) has a much slower growth than did the modern capitalism (1958), the latter period being characterized by a lower time preference (i.e., more savings) compared to the earlier period.

The key element in the anti-deflationist argument promoted by keynesians is that deflation induces people to consume less, which causes decline in profits, employment and, consequently, in prosperity. But instead of declining, standard of living were rising. And even the logic that current consumption increases investment is erroneous. Investment (especially long-term investment) is meant to satisfy consumption in the future. And investment is possible only by deferring consumption.

The debated causes of the Great Depression in the literature

Then, if price declines were not responsible for slower growth, what could be the explanation(s) ? One serious argument is inefficient knowledge and skills. Aldcroft (1964, pp. 118-120), Ashworth (1966, pp. 29-30), Saul (1969, pp. 43, 47-48) and Glynn & Gospel (1993, p. 115) agree that educational inefficiencies, e.g., focusing too much on the theory at the expense of practice or producing clerks and shopkeepers instead of skilled workers, could have impeded economic growth. Ashworth noted :

Cf. Final Report of the Royal Commission on the Elementary Education Acts, England and Wales, 1888, C.5485 which points out (p. 142) that "it is commonly said" that the existing system of elementary education tended to discourage the production of skilled artisans and prepared too big a proportion of boys to become clerks and shopmen. The Commission apparently accepted this view and sought a remedy. The Report also stressed the serious inadequacy of the elementary schools in communicating knowledge to their pupils (p. 133). Cf. also Report of the Royal Commission on Secondary Education, 1895, C.7862, which stressed bad teaching methods and a shortage of trained and suitable teachers as the worst defect of secondary education (pp. 70-2 and 326). The report maintained (p. 72) that, in the average grammar school, science was taught so inefficiently as to be deprived of any real educational value.

The less efficient educational system compared to that prevailing in the U.S. and Germany may explain why Britain had a major problem in keeping up with them (Floud, 1981, pp. 8-9), although the U.S. and Germany have also experienced a deceleration in industrial production between 1860-74 and 1870-97 (Coppock, 1961, pp. 214, 221-222). Saul (1969, p. 46) argues that Britain was lagging behind in steel-making, and one possible cause is the lack of adequate skills on the part of steam-engine makers in, e.g., building diesel engines. The inability of engineers raised in craft traditions to undertake the wholesale rethinking of productive processes necessary to manufacture by mass-production methods was another. If one wonders how Britain has led the rest of the world in the Industrial Revolution, Crafts (1995b, p. 765) reminds us that it was despite of her formal education system. We must remember, however, that this is a qualitative, not a quantitative argument. We don't know how much it has really impacted economic growth. Only that it is a potential factor of unknown importance in explaining the decline in labour productivity during the Great Depression (Coppock, 1961, p. 229; Crafts & Mills, 2004, p. 170).

According to Musson (1959, p. 206), there is more. The inability of Britain to modernize her plant and develop new processes may be due to deficiency in technical education, but also to conservatism and heavy costs of replacing old plants. As for conservatism, british entrepreneurs (and also workers), unlike the americans, seemed indifferent, reluctant to flexibility about the need to adopt new, e.g., labour-saving methods (Aldcroft, 1964, pp. 114, 126-128, 130-131). This evidence is best illustrated through the history narrated by Coleman & MacLeod (1986, pp. 591-593, 600-601) although a limitation of such account is that it may not necessarily provide a random sample of british behavior weighted for the importance of each industry (McCloskey & Sandberg, 1971, pp. 96, 99). The reluctance in the adoption of labour-saving methods, if true, is relevant because when the additions to the capital stock yield diminishing returns (but see discussion below), capital accumulation is not anymore an independent determinant of growth but is itself determined by the rate of technical progress (Aldcroft, 1964, p. 115). So, technical progress (which includes new machines and processes but also better methods of organization and use of more skilled labour) is the final determinant of growth. According to Aldcroft, british businessmen were unwilling to invest in new technologies, despite the fact that the net capital formation as % of net domestic product is 6.8% in 1875-1894 as compared to 7.0% in 1855-1874 (Saul, 1969, p. 41). But McCloskey & Sandberg (1971, pp. 103-104) affirmed that this theory is empirically rejected and that, in theoretical grounds, one can easily guess that higher profits from adopting a new technique would undoubtedly alert and convince other entrepreneurs about its profitability. As for high costs, deflation may not be responsible. As Musson (1959, p. 206) noted, real costs for iron industries have risen in Britain but have fallen dramatically in the U.S., despite both economies were experiencing deflation. Saul (1969, p. 53) has noted that deflation wasn't associated with a decline in investment in other countries.

British retardation is overwhelming. For instance, Aldcroft (1964, pp. 121-122) tells us that Britain was the pioneer of machine tools, but became outdistanced by the U.S. when in the 1880s the price of machine tools in the U.S. had fallen to half that of the equivalent british tools. Aldcroft provides an explanation :

The secret of the American and German success in machine tools was due to the fact that they concentrated on the production of large quantities of one or two standard tools in large, highly specialized and efficiently equipped plants. In contrast, in Britain a very large number of relatively small and inefficient firms existed producing a multiplicity of articles and some of them 'seemed to take a pride in the number of things they turn out'. Costs of production in Britain could have been reduced appreciably if many of the older works had been well planned on a large scale, equipped with plant of the most efficient kind and if the character of the production had been standardized. But in fact there was 'generally an absence of totally new works with an economic lay-out', and it was not until the war 'opened the eyes of manufacturers to the advantages of manufacturing in large numbers instead of ones and twos', that British machine-tool makers made any serious attempt to streamline their methods of production.

This problem is not inherent to the Great Depression. Even by 1939, the shipbuilding industry was badly out of date, compared to U.S. and Germany and in general by 1914 there was hardly a basic industry in which Britain held technical superiority except perhaps pottery (Aldcroft, 1964, p. 117). The outdated machineries and processes may well explain why Britain has seen a large decline in the proportion of manufactured goods (products made from raw materials using machinery) in her exports (Musson, 1959, pp. 224-226). Since Britain essentially was exchanging her manufactured goods versus primary goods (i.e., raw materials), foreign competition made Britain less able to pay for her food imports with manufactures, while at the same time foreign agricultural competition depressed her agriculture and increased her dependence on foreign imports. One potential cause is the smaller size of british firms, loosely coordinated, compared to her main competitors, german and american firms (Glynn & Gospel, 1993, p. 114). As explained before, smaller firms are expected to have more difficulties to get long-term loans for the purpose of intensive productive investment.

Overall, the idea that the adoption of new techniques could have improved british growth has been challenged by McCloskey & Sandberg (1971, p. 105) who note that if the lost output was as much as 5% in the basic industries usually considered poorly managed (steel, coal, cotton, chemicals and railways) the british national income would have been lower than it could have been by only a little over 1%.

Many authors (Musson, 1959, pp. 207-210; Aldcroft, 1964, pp. 129, 133; Richardson, 1965, pp. 131-135; Saul, 1969, pp. 44-45, 51) seem to agree on the fact that Britain has lost her industrial leadership, as a result of slower growth, due to her early and long sustained start as an industrial power. It has been argued that although the early start hypothesis does not make sense theoretically speaking, it made sense on practical grounds (Saul, 1969, pp. 44-45). The early start hypothesis is also accepted by Harley & McCloskey (1981, pp. 64-65) as an explanation for why Britain was more specialized in the less sophisticated industries. The fact that british exports during the 19th century were heavily concentrated in a few basic industries that had been in the forefront of the industrial revolution can account for why exports have declined given that Britain was unable to shift toward sophistication. Richardson (1965, pp. 133-134) put it this way :

The rate of growth of an industry is bound to fall off for a number of reasons. First, there is the simple fact that a high growth rate cannot be maintained for ever. 'It is a natural development, and almost a truism, that the rate of expansion of industry, measured in per cent., must decline during the course of an industrialisation process. A rapid percentage increase in the beginning of an industry's existence cannot continue indefinitely without retardation, as otherwise production would soon reach completely abnormal figures'. There is a tendency for technical progress to slacken as an industry expands; cost reductions in a new industry are limited by the character of the technological basis of the industry itself, and once the initial breakthrough is made, further refinements will tend to yield diminishing marginal cost reductions. Merton's investigations in the 1930s showed that there is a skewness in the rate of innovation in a given industry weighted heavily towards the early phases of its growth. Again, as technical progress advances, many particular improvements are merely new ways of producing existing products: in the absence of a rapid resurgence of demand for these products, this will make for natural retardation in individual sectors. Similarly, the spread of industrialisation throughout the world will tend to retard growth in a given industry in any one economy. Exhaustion of raw materials may ultimately exert a dragging influence on an industry's growth curve. Finally, on the demand side, retardation will follow from the fact that as products age the level of demand for each individual product (other than replacement demand) will tend to reach saturation point, and rising real incomes cannot stave off this point indefinitely.

In particular, Richardson (1965, p. 147) denounced the fallacy of considering a given period in isolation of what precedes and follows it. He argues that any tendency for the aggregate rate of growth to decelerate may be (and usually is) outweighed by compensating forces. To illustrate, Richardson (1965, p. 143) shows that industrial growth during the 1880s was incredibly slow, while foreign investment (as shown by the exports of capital) and the rate of income growth were both high. Such investment helps to increase income in at least 3 ways : by financing cost-reducing transport innovations abroad and thus improving the terms of trade (as shown by the data), by promoting the export industries (but not new growth industries), and by adding to Britain's invisible receipts. Richardson (1965, pp. 144, 148) believes that the reason is due to lower prospective rate of return in investing home while the conditions abroad induced huge investments to be made, a view that McCloskey (1979, pp. 539-540) would certainly agree with. The reason invoked (Richardson, 1965, p. 141) for the lack of investments at home after 1850s-60s is the lack of major innovations until the period of 1890s which made possible the growth of motor-car, electrical engineering, rayon and other new industries. If investors seek industries with the best opportunities of growth, we can expect them to be investing abroad if their own economy has reached a point where it awaits further innovations. One problem with this view is that the diminishing return on capital must assume, quite unrealistically, that capital is neither lumpy nor highly specific but is instead homogeneous and easily divisible. For this reason, Pollard (1985, p. 502) makes the point that there is no certainty that adding to its quantity will necessarily reduce its returns if investments are shifted from overseas to home. Pollard (1985, p. 502) also argues that the diminishing return on capital assumes full employment and constant technology, and that, since these assumptions are rejected, if capital is invested at home, it might have served to reduce unemployment without endangering the rate of return on capital. At the same time, Musson (1959, p. 210) and Pollard (1985, p. 507) affirmed that investment abroad was particularly effective, and probably yielded more in real gains, than investment at home would have done, because it was combined with idle or underemployed other factors abroad. That hypothesis, however, makes the implausible assumption that Great Britain was at full employment (see also McCloskey, 2009, pp. 24-25). Still, consistent with Edelstein's (1981, pp. 78, 80, 86) conclusion, Chabot & Kurz's (2010) analysis confirms that british investors send so much of their capital abroad precisely because this is where the returns were greater and perhaps due to diversification of risks. One reason for this is that it helps to reduce the costs of overseas transport (among other things) and ultimately the cost of british imports of food and raw materials (Edelstein, 1981, p. 70). Even granted this point about the heterogeneity of capital, the view that the lack of major, revolutionary inventions (such as the steamship in the 1850s-60s) accounted for the slower growth during the Great Depression remains very plausible (Musson, 1959, pp. 207-208). Richardson (1965, p. 147) expresses the idea in this way :

The retardation after 1870 can best be explained by referring to the preceding period: the rate of growth was high between 1780 and 1870 because during this time the basic industries were being developed, the transport system built, urbanisation extended and the most consequential technical advance of the time, steam power, applied to a range of industries. Once these tasks neared completion, awaiting some new major technological solution, the growth rate was bound to fall.

At the same time, that argument loses force when we consider only the steel industries because the U.K., U.S., and Germany all started with comparatively low levels of output, and while the U.K. maintained her position in the 1890s, she was left behind in the race by 1913 (Coppock, 1964, p. 392). Also, Wilson (1965, p. 192) doubts that innovation has the "monopoly" of growth although he provides no substantial argumentation. On the other hand, Crafts & Mills (2004) reported that the capital-deepening contribution of steam engines to industrial labour productivity and output growth rose steadily over time, from 1800-30, 1830-50, 1850-70, 1870-1910. This means that the slowdown in growth after 1870 can't be explained by a waning contribution to growth from steam power. Instead, its growing contribution to growth at the end of steam engine revolution indicated a greater british dependence on steam. Although that does not mean there were new, great innovations, its (negative) impact on GDP should have been mitigated, as the hypothesis of technological changes predicts that "after the leading sector has been adopted for a number of years, its influence on aggregate output declines, and before new leading sectors can be put in place, overall output growth declines" (Bordo & Schwartz, 1981, p. 111). Yet there might be some other factors explaining the declining rates of economic growth. On the one hand, Crafts & Mills (2004, p. 170) report that labour productivity growth in two of the steam-intensive staples, namely, coal and cotton, accounted for much of the overall labour productivity slowdown after 1870, and that for coal the decrease in labour productivity growth was the result of the declining quality of natural resources and labour inputs. On the other hand, the slowdown in labour productivity has also been associated with a great decline in the growth rate of capital per worker for both coal and cotton (Crafts & Mills, 2004, p. 161, fn. 3), although the ratio of capital formation to national product shows no decline (Kuznets, 1961, Table 3). To defend the idea that capital formation has been the main cause of the decline in economic growth would be a difficult task again, since Coppock (1961, p. 229) affirmed that it is doubtful if the rate of capital accumulation per head in manufacturing industry fell sufficiently after 1870 to account for the decline in labour productivity growth by itself.

Some authors (Brown, 1965, pp. 48-49) argued that the slowering in growth and the increasing consumption could be attributed to declines in exports. For Saul (1969, p. 38), total consumption per head was influenced significantly by external factors, the improving terms of trade and the rising trends in other sources of overseas income. Saul (1969, pp. 19, 53) has reached the following conclusion :

The swings of home and foreign investment are said to have brought both low growth and sagging prices in the late 1870s and 1880s and again from 1901 to 1910. ... The relative changes in international trade prices moved against Britain's suppliers and by so doing helped to raise the standard of living at home, but the reduced purchasing power it entailed overseas may have been an important factor in the retardation of British exports and, through them, of growth.

The terms of trade (ratio of export prices to import prices; see Harley & McCloskey (1981, p. 54)) seemed to be an important factor. So, it deserves to be discussed more thoroughly. According to Musson, the terms of trade may explain some of the increase in unemployment. Musson (1959, p. 217) stated that the unfavorable shift in the terms of trade, together with the growing volume of imports and decline of exports, has worsened Britain's balance of payments position in the later 1870s, while the favorable movement from the early 1880s onwards eased it, since british people were getting greater quantities of food and raw material imports in return for a given volume of manufactured exports. The improvement in the terms of trade, Musson argues, was the main factor in bringing about an improvement in real wages and the standard of life, for the decline in the prices of imported wheat and other foodstuffs led to a reduction in the cost of living. At the same time, this positive shift in the terms of trade had harmful effects on the export industries, causing their employment levels to go down in the late 1870s. The modest improvement since 1880s didn't coincide with lower rates of unemployment, however. Also, according to Coppock (1961, p. 218), the combined effect of the changes in the supply side (growth of supply and falling transport costs) on the trend in the terms of trade must have been modest in size at least over the full period of the Great Depression.

Musson (1959, pp. 218-219) explained that the terms of trade could be easily mis-understood. British imports are valued Cost, Insurance and Freight ("C.I.F.") while exports are valued Free On Board ("F.O.B."). The latter means that the seller pays for transportation of the goods to the port of shipment, plus loading costs. So, a favorable terms of trade movement does not necessarily say what it means.

British imports are valued "c.i.f." in the Board of Trade returns, while exports are valued "f.o.b.," so that the consequence of reduced shipping freights was naturally an improvement for Britain in the terms of trade, and Britain was certainly better off as a result; but, though the terms of trade moved "unfavorably" to the countries supplying her with imports, their real position was not necessarily worsened. For example, the chief factor in the great fall in the prices of American food products in the British market was the fall in freight rates: prices on the American farm fell much less. Moreover, as a result of the opening up of new territory and agricultural mechanization, farming costs were reduced, while output and exports were enormously increased. Britain, in particular, was importing greatly increased quantities of American farm products. It seems doubtful, therefore, if the "unfavorable" movement in the terms of trade reduced the purchasing power of American farmers and so checked imports of British manufacturers. The same was true for other primary producing countries, from which British imports continued to grow rapidly.

Another leading factor to the change in terms of trade is the currency's value. Solomou & Catao (2000, Figures 6 & 10) discovered that import price declines (and increases) during the period of 1879-1913 are partly due to nominal exchange rate appreciation (and depreciation). In U.K., when the real exchange rate increases (diminishes), the export growth diminishes (increases). On the other hand, the terms of trade increased during the 1880s and remained stable during the 1990s while the real exchange rate increased during the 1990s.

What is without dispute, however, is that Britain's share of world trade has diminished during the 1873-1896 period. Saul (1965, p. 17) made the suggestion that since Britain was bound to lose some ground in world trade as others industrialised, there were several solutions. One was to shift to higher quality goods, another was to cut costs, the third was to switch to new markets, often helped by capital exports - a reasonable solution in the short but not in the long run. But he then argued that none of these propositions is convincing. Other propositions as for the cause involved international competition and tariff protection (Musson, 1959, pp. 222-228). As described earlier, U.K. failed to innovate and develop modern techniques of production, as opposed to U.S. and Germany. The fact that the growth in world trade in manufactures has declined relatively to world manufacturing production would have also severely impacted Britain for which the exports account for one quarter of GDP (Musson, 1959, pp. 219-220). And Hatton (1990) agreed. In addition, while Britain maintained a policy of free trade, some other countries revert back to protectionism due to the environment of depression, and tariff protection was growing during the 1870s-1890s, notably in european countries such as France, Germany, Spain, Italy, the USA, Brazil and elsewhere (Hatton, 1990, p. 583). Britain's terms of trade was favorable with regard to unprotected countries but was unfavorable with regard to protected countries. Curiously, Hatton (1990, p. 583) informs us that tariff protection may not have a great impact on trade, despite showing the evidence against such a view. Hatton (1990, p. 578) first said that the relationship between exports and GDP is clear except at the end of the 1890s due to housing boom that complicates the relationship. Hatton (1990, p. 591) then demonstrates that what determines british exports in major part was world trade rather than relative export prices (i.e., across countries). Specifically, 50% in the loss of Britain's share of world trade is due to inelasticity of exports with respect to world trade and 30% of the loss is due to deteriorating competitiveness. This has caused Britain to export less, while importing more and more foreign goods, which may explain the decline in prices in Britain. Musson (1959, p. 225) writes :

Imports had been growing gradually for many years, but it was not until the seventies that the railway and steamship brought in a flood of cheap foreign imports, which seriously depressed certain sections of British agriculture and destroyed the balance of the British economy. Britain rapidly became dependent for most of her food on overseas supply.

As Kennedy (1974, p. 436) has remarked :

Although it has long been recognized that all industrial countries experience a decline in the proportion of GNP invested during a recession, Britain was uniquely dependent on external stimuli to end her investment slumps.